What if a train doing 1,200 km per hour were to say more about man’s evolution than other discoveries?

12 of January of 2017

We humans are passionate about moving. And about speed. We crawl before we talk, and ever since we appeared on the planet it seems we have done nothing but travel to all the corners of the Earth, at an ever increasing speed. Even when satellite pictures have shown us just how small our planet really is, we continue to push technology to the limit.

Perhaps this is what George Edwards was thinking when in 1958 he appeared before the Royal Aeronautical Society and declared to its members that man’s progress could ultimately be measured in terms of the maximum speed attained by the average citizen. And this is very relevant, since the Hyperloop, a bullet train moving within a vacuum tube which will reportedly reach a speed of 1,200 km/hour, aspires to soon become one of the transport systems of the future.

How do you measure how advanced we are technologically?

Looking back on how, as Europeans, we have fought against each other at various points in history, it is easy to say that “Today we are more civilised, more public-spirited, or have evolved more”. However, it is difficult to obtain objective data to prove that this is so.

Do we gauge human evolution based on the discoveries made, on the number of patents filed, or the bits on Wikipedia? Or perhaps based on the number of laws we generate in our bureaucracy? And how can we avoid being tempted to cheat with the methods used, or making mistakes? What is obvious is that we need some type of objective, equal and measurable system.

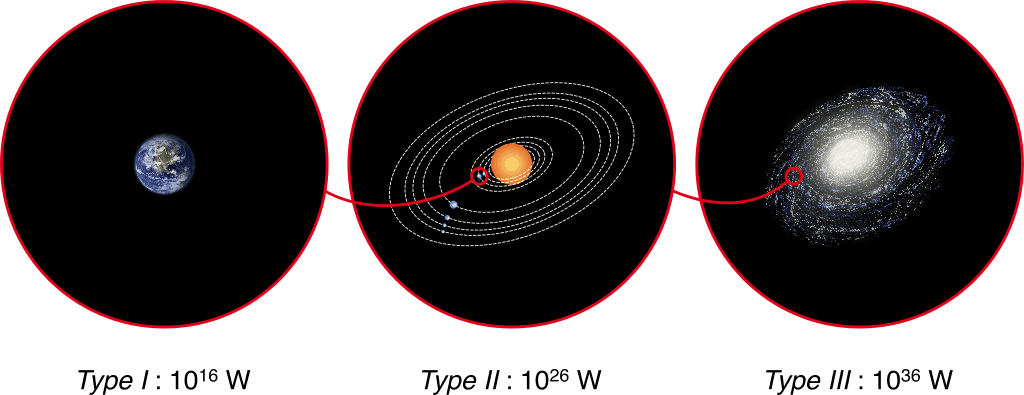

Estimated energy consumption in three types of civilisations according to the Kardashev scale. Source: Kardashev.

And so Nicolái Semiónovich Kardashev measured the level of technological advancement based on the amount of energy used, distinguishing three types of civilisations:

- those that make use of their own planet,

- those that make use of their solar system,

- and those that make use of the whole galaxy.

A system which is certainly up for criticism. For example, if we were to forget about green energy sources and burn ten times more carbon than we do now, we would appear more technologically advanced on the Kardashev scale, something that seems rather difficult to justify. Moreover, this energy is not equally distributed. Today we know that a large part of our planet is energy poor, whereas a small part uses an excess of energy, so this cannot be used as a true indicator, which would be somewhere below this level.

To avoid this problem, the George Edwards scale included a tag in its definition which made it clear that the speed measured was that of the average citizen. In other words, if a group of multimillionaires decided to travel to space every weekend, this would not affect the measure of how technologically advanced we are.

At what speed have we been moving up to now, and how has this affected us?

George Edwards was an Englishman, and as such was used to determining magnitudes in the most complicated way possible. The more complicated, the better. Instead of using the universal unit of measurement, or at the very least imperial units of speed such as knots or miles per hour, he used “the distance a person might normally cover in a 12-hour day” for measuring the technological advancement of humankind. A distance he made even more complicated by expressing it in nautical miles. I will allow myself the liberty of using kilometres.

For almost our entire history, the maximum distance covered was what a person’s legs could muster, approximately 32 km per day. By using horses we managed to double that distance to 64 km, and then managed to double this again (120 km) when we learned how to adequately pave roads and manage the freshness of the horses. Thus, just before the Industrial Revolution an English gentleman (ladies used to travel by carriage in those days) could ride for 12 consecutive hours by changing horses.

Caprotti locomotive, Source: Wikipedia

With the Industrial Revolution came the train, which could cover 820 km per day under steam power. The large locomotive boilers did not need to rest, and driver shifts meant that only a first carriage of coal was needed for the train to keep moving all day.

In 1940 or thereabouts aeroplanes became available to the general public, covering distances of up to 2,000 km. But aviation did not set limits for itself, with jet engines coming on the scene to cover 8,800 km, followed by supersonic planes. The latter soon disappeared, however, but planes such as the Boeing were able to cover a distance of close to 11,000 km every 12 hours.

For the first time in decades, we are on the doorstep of a transport system capable of travelling at 1,200 km/h, and available to the general public: the Hyperloop. This would increase Sir George Edwards’ distance (yes, he was knighted for services to England) to almost 15,000 km. This is definitely a measurable and comparative figure, which is precisely what Kardashev was looking for.

What the Hyperloop will bring

For a start, it will bring cleaner air, thanks to its method of propulsion. The Hyperloop is a launching system similar to the train in its physical conception, but with the passenger cabin travelling through a tube. Some critics have compared the ducts in the Futurama cartoon series with the Hyperloop. And in general terms they are right, since a vacuum is created in the tube and there is therefore no air friction, thus saving masses of energy during forward movement and making it possible to reach speeds never before experienced in land transport.

Futurama vacuum tubes, showing the cartoon characters travelling through them. Source: Myfuturama.

But that’s as far as any comparisons with the cartoon series go, and it is altogether possible that within two centuries the Hyperloop will be the subject of as much study as trains are today. According to Elon Musk, inventor of the Hyperloop, this is a “new way to move people and things at airline speeds for the price of a bus ticket”. And that’s where the magic lies: the cost to the passenger.

History has shown us, starting probably with the Romans, that the moment you enable people to move at a greater speed than they did before, economic systems start booming, money starts circulating and science takes off as never before. Get people moving (literally) and society will prosper.

The Hyperloop was presented in 2012, it was subject to a global brainstorming of ideas throughout 2014, and passed its first successful test in 2016. It will probably open its doors to passengers in Spain in 2019, although there are experts who believe that this won’t happen. In less than a decade it can change this country, linking Madrid and Barcelona in just 30 minutes. The same would hold true for hundreds of other routes all over the world. The technology is there, it has been tested, and it is affordable. The problems now are more of a bureaucratic rather than technical nature.

Wanderers, (nomads). A short film by Erik Wernquist, narrated by Carl Sagan

It seems that breaking the 1,000 km/hour barrier brings us ordinary citizens closer to the limit which Carl Sagan set some time ago for the upper atmosphere, alluding to our adventurous, nomadic spirit. A speed of which George Edwards would be more than proud; which would mark a leap forward for our civilisation on the Kardashev scale; a speed which Elon Musk has committed to heart and soul with SpaceX.

As I said: we humans are passionate about moving.

There are no comments yet