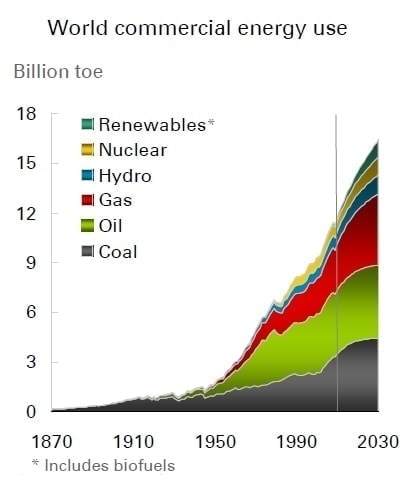

For more than a century the world’s foremost economies have been almost exclusively powered by fossil fuels. Our heating, transport and electricity needs have grown exponentially, and will require ever more sources of affordable energy to satisfy surging future demand.

Coal, originally used for heating and smelting among other purposes, really came into its own during the age of industrialisation and the steam engine, where huge amounts of the raw material were required to feed all manner of energy-hungry processes. As a fuel it remained dominant until after World War II, when the internal combustion engine and commercial aviation ushered in oil as the new champion, owing to its abundance, fuel density and portability.

Since then, many of the world’s leading engineers have employed their talents searching and drilling for oil and natural gas reserves, pioneering new and ingenious methods of extracting ‘black gold’ from what are often some of the most inhospitable environments on the planet. New processes and technologies, improved efficiencies, recovery of deposits previously considered uneconomical, and discoveries made in recent years such as those in Brazil –one of largest finds for several decades, offshore from Rio de Janeiro– have meant that ‘proven reserves’ have kept up with demand, despite record consumption. The most bearish estimates still present us with perhaps 50 years’ supply.

Yet in recent years critics have become increasingly vocal in claiming we are now addicted to these finite fuels, with such voracious consumption inflicting permanent damage on a planet already stricken by an unceasing demand for natural resources. Debates abound over carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions arising from combustion for heating, transport and electricity.

Likewise, most governments, including those of the EU, are now looking to decouple their economies from uncontrollable geopolitical forces and unstable regions, to develop greater energy independence, and, although somewhat reluctantly, have strengthened their commitments via binding international agreements.

Of course this is nothing new to scientists, who several decades ago began to express their concerns over how our energy needs would be satisfied in the medium and longer-term, warning that we must change the way we power our economies. From this concern was borne the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), whose remit it is “to provide the world with a clear scientific view on the current state of knowledge in climate change and its potential environmental and socio-economic impacts.”

Many of the necessary changes are still taking shape, and will continue to do so, resulting in the establishment of long-term plans to decarbonise energy production and key industries. This has nevertheless required the use of both the carrot and the stick, to enable meaningful emissions reductions and improve ecological footprints. Various aspects continue to be hotly debated, especially considering the implications for the BRIC and major developing countries.

Planes, trains and automobiles

Fulfilling a key role in the development of the world economy, transport is a sector that has become undeniably dependent on a single source of energy for its needs: petroleum. Whereas hybrid fuel, hydrogen cells, improved battery technologies, renewable fuels and even solar power seem increasingly viable solutions for many –promising to furnish us with many environmentally-friendly or even carbon-neutral personal and commercial vehicles over the next few decades– in the case of aviation, the reality is rather more complex.

What sets air travel apart is its dependency on large amounts of high-density fuel, hitherto something only fossil fuels could effectively satisfy. The aviation industry contributes nearly 8% to world GDP and is logically responsible for a small but growing proportion of GHG emissions: according to the IPCC, aircraft currently produce around 2% of total global CO2 emissions, although reports suggest nitrous oxides and condensation trails produced at near stratospheric levels could mean the impact on global warming is somewhat higher.

With the help of Boeing and Airbus, the world’s largest manufacturers, commercial aircraft are now significantly lighter and more fuel efficient than ever before, yet such is the debate over how to reduce the carbon footprint of the sector through new regulation –currently in the spotlight regarding the January 1st introduction of a carbon levy on EU aviation and its inclusion in the EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS)– tensions have at times escalated to include the threat of trade wars.

So what does the future hold? Besides exploring new engine technologies, traffic management and policy mechanisms, for several years now –in an effort to cut fuel costs, insulate against price spikes and curb emissions– the aviation industry has been wholeheartedly investigating how to switch from fossil fuels to alternative ones. This is where some of the greatest innovation is set to occur.

To get an idea of the magnitudes involved, airlines spent $178bn on jet fuel in 2011, a whopping 25 – 40 percent of their total operating costs. The US military –the largest buyer of transport fuel in the world– is also eager to get involved and recently made the first of several $170m commitments to aid development of new technologies.

In the second part of this article, we’ll see specifically how the aviation sector is looking to tackle its future energy challenges.

There are no comments yet