Waste as a source of resources: comments and opportunities

17 of January of 2016

With the world in a deep economic crisis, driven by rising oil and commodities prices, there is increasing demand to make better use of the resources available in waste. Traditionally, certain fractions of waste have been recovered (metals, plastic, organic material, etc.), and others have been used as fuel for energy production. However, a large amount of the waste we send to landfills includes materials that could be used productively. Although there are significant technical, economic and legal difficulties, we really don’t have a choice, and this option is an excellent opportunity for entrepreneurs.

In my first entry for this blog, I asked the question: what is waste? and reached the conclusion that everything a person uses during the course of his or her life ends up as waste, sooner or later. Therefore, it’s clear that waste contains all of the materials and products that society uses, making it a good potential source of commodities, which could compete with and help preserve natural sources.

In a previous article for this blog, I took an unconventional view of energy-from-waste, approaching it in terms of physics and chemistry. Now I’d like to examine the other side of the process, namely material recovery, and consider some aspects that aren’t usually discussed and which government officials and politicians often have a hard time understanding. Clearly, waste’s potential has been known for a long time. In fact, urban mining (urbanmining.org, urban-mining.com), which is currently a well-established idea, has been the subject of discussion for decades. It considers waste as a minable resource, to which traditional mining techniques can be applied to recover certain components, primarily metals.

What has changed to put urban mining of waste at the top of the political agenda? In my opinion, there are three reasons, about which I could write three extensive articles; however, I will try to summarise them briefly here.

1) The possibility of depleting some of the traditional resources, which would lead to shortages.

2) Certain troubled nations’ monopoly over the main sources of some of the key elements needed by our society. One important example is rare earths, of which China produces 95% of the world’s total and which are essential components of electronics. Another example is lithium, vital for making the batteries for those electronic devices, as well as for electric vehicles; Bolivia accounts for 80% of total known reserves.

3) The fact that we are running out of landfill space, and the social difficulties involved in expanding them or creating new ones, together with ever-increasing costs of waste collection and treatment. With the onset of the crisis, the European Union has become very concerned about the enormity of this problem. As a first step, it issued two documents assessing our situation and setting out a roadmap for Europe with a view to reducing our dependence on external suppliers:

• Critical raw materials for the EU. Report of the Ad-hoc Working Group on defining critical raw materials. European Commission. Enterprise and Industry. June 2010.

• Roadmap to a Resource Efficient Europe. COM(2011) 571. 20.09.11. The European Commission proposes several lines of action, one of which is the recovery of the raw materials found in waste.

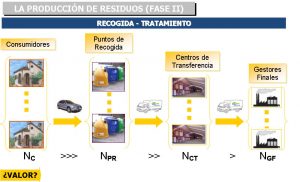

Although Europe lacks rare earth and lithium mines, it has thousands of tonnes of devices which contain those elements and which will end up in the garbage very soon. Therefore, it is imperative that we develop the necessary technology here in Europe to recover those elements from our own waste and to use them as raw materials in industry. An example of how troublesome the problem could become for Europe’s economy in the short term is that one of the measures included in the European proposal involves eliminating environmental protection (implemented by member states in compliance with EU directives) in areas where those mineral resources still exist. But that is a matter to be discussed another time. Up to this point, it all appears quite coherent and reasonable. However, there are some implicit rules which should not be ignored. We could summarise the current consumption model as follows: millions of different articles are produced in thousands of factories throughout the world, and they pass through multiple intermediaries until they reach millions of consumers, i.e. us. This system is illustrated with the flowchart below.

This system works because the number of participants increases in each phase, as does the value added, so everybody wins. But let’s look at the flowchart below and see what happens when we eliminate the product and it becomes waste.

Two major differences stand out: the number of participants decreases in each phase, from millions to a few hundred at the end, and the value is increasingly negative because of additional costs (bins, collection and transport vehicles, and transfer stations, etc.) that nobody wants to assume. In short, the current consumption model is characterised by three factors: It adds significant dispersion (entropy) to the Earth’s global system.

- It dilutes responsibility (people think someone else will handle the problem.

- Value is added only during the first half of the model.

Therefore, the solution for closing the cycle and recovering materials requires giving value to waste through:

- A clear-cut assignment of responsibilities throughout the process.

- A supply of energy and information for reverse logistics in the second phase.

- Capital.

On that basis, we can see what requirements must be met so that we can achieve material recovery. Below is a summary of the conditions which I consider that government officials responsible for waste management find it hard to understand:

1) It should be required or permitted by law.

2) It should be collected separately or it should be technically and economically viable to separate it from other waste.

3) Someone should have an obligation or interest this area.

4) There must be appropriate processing technology.

5) The process as a whole should be profitable, or society should bear the costs.

6) There should be a market for the recovered materials and it should remain stable over time.

Are these conditions impossible to fulfil for most materials? Until recently they were; however, the situation is changing quickly as a result of the two factors I mentioned earlier: the depletion and rising prices of natural resources. Accordingly, we are getting increasingly closer to break even point. I believe this situation offers an excellent opportunity in a time of crisis for companies specialised in waste collection and treatment. We shouldn’t allow the Germans to develop the technology and then sell it to us. They’re already working on this area and we are beginning to see their marketing efforts.

There are no comments yet