Trying to understand the reasons for a situation, without reviewing the facts that preceded it, may be a risky exercise, which can give us an incorrect vision, not only of the source of the problem, but also of the solution. That’s why to understand how we begin to ignore the key role of nature in our development, as we emancipate ourselves from it, how we take into account nature, requires an analysis of these features.

How nature went from being All to Nothing

One of the main reasons why the planet is in this environmental situation is undoubtedly the great distance we set up between us and nature at a certain point. Throughout history, the natural environment has been taken as an authentic nourisher, which has allowed the human species to increase their well-being as time has passed to the degree that we can enjoy today.

Since the first human settlements, nature and the benefit it has given us has been worshipped and we have shown gratitude through different representations, which have varied with each group of people or civilization. The Mother Goddess, as a representation of fertility and life in many Paleolithic settlements. Shara, a Sumerian deity representing vegetation. Tialoc, a Mesoamerican deity who represented, among other things, a proto-hydrologic cycle, and Gaia, who represented Mother Earth to the Greeks, are just a few examples.

(Tialoc and Gaia) Source: Wikipedia

If we advance in history, we can clearly identify that nature was extremely present in thought. Thus, one of the first economic schools, the Physiocrats, which etymologically means the government of nature, defended our wealth as a consequence of the natural environment. At a later time, John Stuart Mill, representative of the classical school, identified growth as being stationary, because resources provided by nature are also finite. Paradoxically, the same conclusions were arrived at in the Meadows report, 101 years after Mill’s death, in a clear example of the break of the economy/nature association that occurred at a particular time in history.

The twentieth century, when we stopped thinking about nature

It would not be until the beginning of the 20th century when the definitive break with nature would be reached as a consequence of the emergence of the neoclassical school. This economic school was the first to follow the precept that a certain threshold of wealth exceeding economic growth would be increasingly less polluting and dependent on the natural environment. In addition, the rise of the industrial revolution, where the first mass exodus from the countryside to the city took place, or the technological optimism that fueled the idea that technology could become a substitute for the natural environment created the perfect ingredients for an emancipation that was going to have great consequences and that was going to continue until the 1970s. It was necessary to wait until the last decades of the twentieth century, with the appearance of concepts like Natural Capital and Ecosystem Services, to begin to look for signs of change.

A great paradox

However, before going into depth with the concepts that concern us here, I imagine that readers will have already identified a great paradox: The human vision on the existing dependence on the natural environment underwent a paradigm shift at the same time that more capacity for change on human beings was beginning to take place. Societies lost the awareness that the true sustenance of human well-beings was taken directly from ecosystems and therefore, the consequences of such were no longer evaluated when making decisions. As a result, the process of degradation of the natural environment in the last 50-70 years has been increasing exponentially. In addition, although this has translated into an increase of well-being for a great part of the planet’s population, if it is not reversed it will lead to a sharp decrease in well-being for future generations. And it is future generations who must pay off the debt with nature that we have taken on. For this and other reasons, currently part of the population lives beyond the planet’s capacity to sustain them, as one of the consequences of our famous emancipation with the natural environment, which had us believe that Earth had infinite resources, and that enjoying them was separate from nature.

The Emergence of Natural Capital and Ecosystem Services

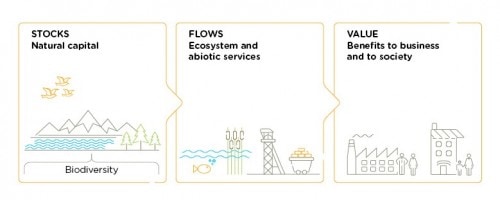

The first step to change was the emergence of the concept of Natural Capital, defined as a stock that generates a flow of goods and services, as revenue over time. To this flow of goods and services, which is the benefit that humans obtain from nature, are called Ecosystem Services.

Nature back in the spotlight

The next step that was taken to make these concepts more comprehensible was to put its implications in understandable language. And so in 1997, Robert Constanza and Ralph D’Arge among others, in what would be one of the first attempts to integrate the economic and environmental models, ventured to calculate how much capital was worth worldwide. In order to do so, they valued a series of Ecosystem Services and reached a dizzying and underestimated figure of $33 trillion. This established a milestone because it was the first valid attempt to put the value of nature into a common language that would facilitate, among other things, decision-making, and ultimately would put the natural environment back into economic analysis, thereby setting the role of ecosystems as relevant in sustaining economies and therefore, social welfare. From here, the view that had prevailed in which Natural Capital had been ignored for decision making, and therefore, the measure of consequences when interacting with it at all levels was going to be discarded. Thanks to this new direction, in 2005, one of the greatest scientific efforts of our history was made, with the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, where the consequences of the transformation of the natural environment for human well-being were measured. This allowed us to build the first clear and unified definition of Ecosystem Services.

Ferrovial’s role and natural capital

Ferrovial is aware of this situation, and therefore launched the plan in 2012 under the Ferrovial, Natural Capital program, with the aim of taking into account the value of Natural Capital in its decision-making. This does not mean that a market value is given to nature, but that its value is taken into account in understandable and common language, so that the impacts of activities it performs can be anticipated a priori and integrated into decision-making. For this reason, we are currently working on the development of a methodology, capable of evaluating this capital through Ecosystem Services, with the goal of applying the principle of zero net biodiversity loss that seeks to reduce the loss of associated biodiversity to zero, and a good application of the Mitigation Hierarchy, where it is no longer intended to restore or compensate for the impacts associated with projects in Natural Capital, to but rather to minimise them and, if possible, avoid them. In this way, the company will have the ability to anticipate trends in the market, to be able to measure the impact of its activities in a common language that allows it to adapt to the possible consequences and even prevent them. In addition, it will be possible to significantly increase its basic environmental information associated with the location of each project that it carries out, which entails competitive advantages in processes such as tenders or our reputational status, and a vision of conservation that is increasingly pronounced and present in our policy and way of acting.

The time came

For all that I have described here, I think it is time to recover that old custom that we had to take into account the natural environment in all that we set up, knowing that it is not an entity independent of humankind and our activities, but an indispensable part of what we were, what we are and what we will be as a species.

Now it is time, not to fall into the tragedy of commons, which the American ecologist Garrett Hardin predicted in 1968, and which is summed up perfectly in the words of Professor Barry Schwartz :

“How to escape the dilemma in which many individuals acting rationally in their own interest, can ultimately destroy a limited and shared resource, even when it is evident that this does not benefit anyone in the long run.” We now face the tragedy of global commons. There is one Earth, one atmosphere, one water source and six billion people sharing them. Deficiently. The rich are overconsuming and the poor are eagerly waiting to join them.”

It is now time to take into account Natural Capital, the Ecosystem Services provided, and biodiversity into account as the most important assets of our development and that of our future generations, with the clear understanding that we depend and will depend on them, forever.

There are no comments yet