They say that creative solutions are born out of complex situations. When the challenge is simple, solutions are trivial and relatively easy to implement; but when requirements are complicated, such as the lack of building space, imagination is unleashed and engineers’ ingenuity shines through to leave us open-mouthed.

This article covers some of the weirdest airports in the world, precisely because of the space constraints when building them. Can you imagine an airport with a road crossing it, an airport that floats on the ocean, or one that is built on hundreds of concrete pillars, or on the very edge of a cliff?

The floating Kansai International Airport

In the 1980s, it was obvious that Osaka Prefecture lacked the space for housing that much-needed airport which the authorities had been trying to put on the map of this mountainous Japanese island for years. And so, in 1987, thousands of workers were mobilised to take part in one of humanity’s largest engineering projects, comparable in scale to the construction of the Egyptian pyramids.

Three years later, the artificial island on which the future airport would be built and the bridge joining it to the mainland were ready. However, the island was eight metres lower than its projected level and slowly sinking into the waters of Osaka Bay.

An airport located in the middle of a bay is a singular architectural feat in itself. But the fact that it was sinking made it the most expensive civil works project in modern history, as the pillars on which the artificial island rested had to be reinforced. The result is Kansai International Airport, under construction in the photo.

If we had to choose one particular feature of this airport, it would be the fact that it isn’t actually floating on the water, but on a series of adjustable pillars – to explain them in a simple and easily understandable way – with sliding joints at their base. Despite it being an area of high seismic activity, the airport suffered no damage in the 1995 Kobe earthquake (of 7.3 magnitude on the Richter scale) which struck just two years after it opened.

The tremor, ‘the costliest to ever strike the country’ according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica, devastated a large part of the island and its transport infrastructure. However, it didn´t affect this new airport in any way. In fact, not even the glass in the windows shattered, even though the floating airport was only 20km from the earthquake’s epicentre.

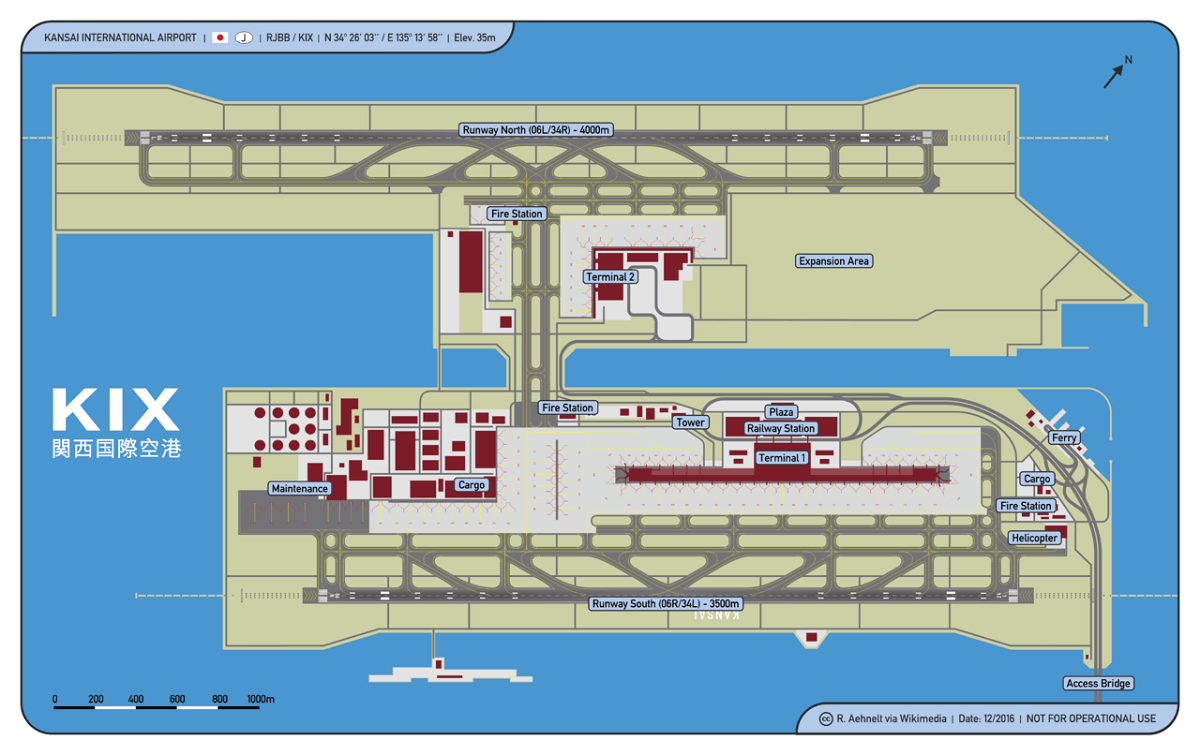

As can be seen from the diagram of the airport shown above, there are more surprises than you may imagine.

For example, it not only houses a medium- and short-distance train station, but also two fire stations (although, admittedly, they are small), various heliports and its own port where local ferries can dock. Plus a couple of shopping centres, an observation post and numerous leisure and walking areas.

Four airports crossed by a road

It is very often said that one of the most stressful jobs in the world is that of air traffic controller. These professionals work in control towers, and are responsible for authorizing aircraft take-off and landings at airports. So imagine what it must be like if, apart from controlling the planes, you also have to keep an eye on the area’s road traffic.

Well, that’s exactly what happens at Gibraltar, Phonsavan, Funafuti and Kodiak airports.

Gibraltar Airport is located in the south of Spain. It opened officially in 1949, but was already used during the second World War as an emergency base for England. It was not until 2006, when it opened for civilian use, that the local CA-34 road (previously the N-351) started to give problems.

Although it had been in use for years, the increased frequency of the new commercial flights now using the infrastructure meant that the whole control and security system had to be redesigned.

Somewhat more exotic from our perspective is Xieng Khouang Airport in Phonsavan (Laos), with its only terminal building shown in the photo above. There are not one but two roads crossing this airport, one of which also acts as the landing strip. Obviously, the flight frequency here is relatively low, so there is not much risk involved in wandering along the runway.

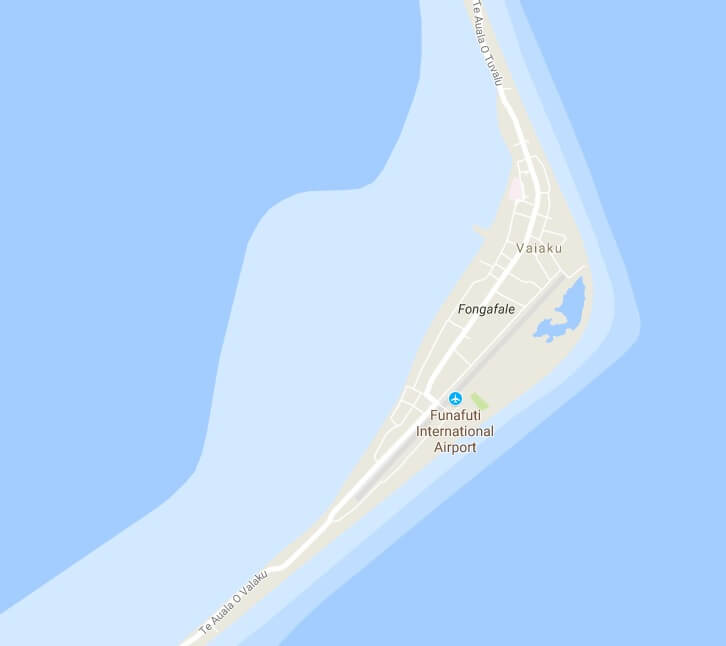

Something similar is true for Tuvalu (Polynesia) and Funafuti International Airport in Funafuti village (above). This is a take-off and landing strip which is easily accessible on foot to any local resident. The village houses are just a few metres away from the strip and there are barely any safety measures.

It’s worth taking a virtual walk on Google Maps to appreciate the size of the airport compared to Vaiaku, the nearest settlement.

Another singular airport usually mentioned together with the previous three is Kodiak Airport, in Alaska. Located on a projection of land surrounded by mountains and abrupt terrain, it forms a triangle around the village of Kodiak with its runways and taxiing lanes. For years the only way out of the village was by crossing some of these infrastructures. Today, the Rezanof Dr W road which used to cross right through the middle of the airport goes around it along the slopes of the surrounding hills.

A landing strip on 180 concrete pillars

Some people are afraid of flying even though it is considered to be the safest means of transportation to have been invented to date. It is unlikely, however, that this fear will disappear, and even more so if you are told that you will land at Madeira Airport, where the runway sits on concrete pillars:

The island of Madeira in Portugal is approximately the same size as Lanzarote in the Canary Islands, but it has hardly any flat areas on which a plane might land, and those that it does have are taken up by cities and towns.

For decades, the previous airport, located in the same place as the current one, was known as ‘the world’s most dangerous airport’. It’s a reputation that the new airport has inherited, probably undeservedly, since historically there have been other more dangerous ones.

In 2003 the airport underwent an enormous transformation, with the landing strip being extended on 180 concrete pillars. The tallest of such pillars, which reach a height of 70 metres, evidence the huge height difference that must be overcome. A height difference that allows the VR1, a four-lane motorway with a central reservation and hard shoulders of considerable width, to run under the airport.

A bird’s-eye view from the appropriate angle conveys the impression of a massive aircraft carrier resting upon tiny sticks.

Juancho E. Yrausquin and Courchevel, airports on the edge of the abyss

Two other airports which are not for the faint-hearted are those of Juancho E. Yrausquin, on the island of Saba in the Caribbean, and Courchevel, in the French Alps. Technically, Courchevel is a ski station. But on one of its ski slopes sits Courchevel Altiport.

An altiport is an airport built on a mountain. There are eleven of these in the world, of which ten in France and one in Nepal, the Tenzing-Hillary shown in the photo below.

But Tenzing-Hillary is an easy altiport if we compare it with the French one of Courchevel. This slope is known by some skiers as The Slide, and it isn’t difficult to guess why:

The landing here is one of the most complicated in the world because of the incline of the slope and the weather conditions in winter, as the whole valley is at times entirely in the mist. Obviously, it can only accommodate small, light aircraft.

Take-off manoeuvres are notoriously complicated because of the so-called slide effect. A plane taking off from this strip has to carefully calculate the angle of the wings, as the incline halfway down the slope could make it lift off slightly before reaching the required take-off speed… and 537 metres later, the airport simply disappears under our feet.

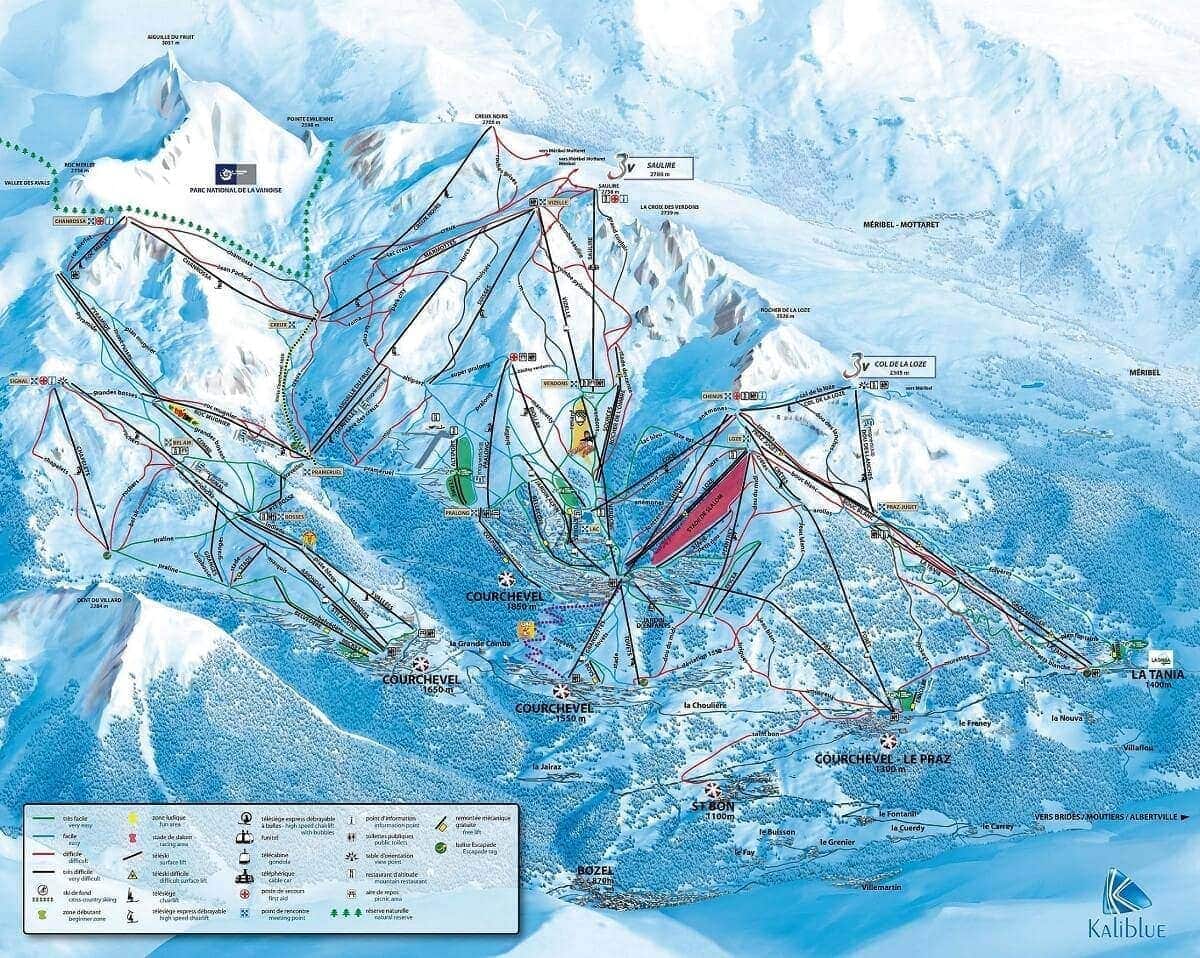

The ski slopes of Courchevel are without a doubt the only ones in the world showing an airport on the map (on the slopes of the Saulire, under the Suisses chairlift).

Juancho E. Yrausquin Airport would appear to be more accessible to pilots, as it is surrounded by green slopes all year round. But nothing could be further from the truth: it is in fact the world’s shortest commercial airport, spanning just 396 metres.

Not only is it difficult enough to lift the nose of the plane over such a short distance, but pilots must also contend with the crosswinds that buffet the island, and counter the depressions or high pressure areas formed by the cliffs towards which the planes hurtle. Luckily, or perhaps because this airport is hardly ever used, no accidents have ever been recorded.

Airports are often the only feasible way to access particular locations in the world, or at least the most comfortable way of doing so. But what happens when you don’t have the space to build an airport? Then it is down to the imagination of those who design and build impossible airports, the expertise of those who fly the planes, and the voluntary or forced adventure of those who use them… all so that we can keep writing about and describing the history of these architectural and aviation wonders.

There are no comments yet