One of the most influential names in the history of film is one you’ve probably never heard of. His name isn’t on the walk of fame, nor inside your anthology of cinema, but if you’re an architect with a soft spot for German expressionist epics, then you might just be the exception.

Otto Hunte was part of a trio of production designers frequently called upon by director Fritz Lang to bring his scripts to life. His futuristic buildings towering over the city of Metropolis are reflected in some of the architecture we see today; a vertical city layered according to the social standings of the population.

Hunte’s team comprised of two other Germans: Erich Kettelhut and Karl Volbrecht, and it’s Volbrecht’s role of Filmarchitekt in Metropolis that got me interested in this story in the first place. Volbrecht helped bring Hunte’s sketches to life. Sketches of a futuristic city that lives forever on-screen but for only a fleeting moment in the real world.

This fleeting moment is a Hollywood obsession. Enormous sets are constructed in backlots for the perfect shot. These take months, sometimes years to construct. For Lord of the Rings, director Peter Jackson even asked the crew to plant real vegetables on set a year before any filming ever took place. This is the detail directors want, and teams of hundreds or more put their talents to use building villages that exist for only a matter of months. So, if the vegetables should look that good, imagine the details obsessed over architecture and aesthetics.

The Village that lasted how long?

Narrow medieval streets, cute, cobbled roads, a certain je ne sais quoi that the French always seem to have. This is Conques; a quaint village nestled in the south of France. It’s also the set of 2017’s Beauty and the Beast. The set of the Disney re-make and the town that it’s modelled on may be 688 miles apart, but they have a striking similarity.

It’s no accident either. Production designer Sarah Greenwood took a whistle-stop tour around France looking for inspiration from old chateaus and traditional architecture that would help recreate France in the 1740’s. A team of over 60 sculptors and crew worked hard to build the 30-foot high sets over an 18-month period, and it’s sometimes impossible to differentiate the intricate details of ornaments and façades to the real thing.

But the real world of production is no fairytale. It was actually possible to shoot the film in the village, but when producers did the math, they got back to Sarah with a proposition: “It’s going to cost X to go to there, can you make us this village (for less)?”

Pulling inspiration from all the elements that they loved on that trip, Greenwood and the team set to work in the backlot of Shepperton Studios and began the task of bringing the village to life. One of the reasons a tangible village was created was that the Beast, the protagonist, was to be computer generated. Producers were worried too many digital effects would be a little jarring for the viewer, especially as this was the real-life adaptation of the 1992 cartoon original. Only the ‘real’ thing would do.

Artists and construction workers brought the village to life by carving, sculpting and plastering their way around the enormous set. Sketches were made, scrapped and re-drawn over and over again.

Over the course of construction, the team built, among other things, a 12,000 square foot faux marble floor, a 9,600 square foot forest (including real trees and hedges that took 15 weeks to put in place), and a 30,000 square foot village, including a cottage, school, church and village square. All of this was built by a crew of over 1,000 for just 3 months of filming between the months of May and August 2015.

If you can’t build big, build small

When your city is too big or budget too small, just remember you can always fall back on the pioneering techniques of filmmakers in the 1920’s. Wes Anderson’s Grand Budapest Hotel might have won an Oscar for best production design, but there were no tricks used that we hadn’t seen before. Metropolis might look a little fake today, but it was this particular brand of artificiality that Anderson wanted to re-create.

The artificial feeling of Metropolis comes from the techniques used to construct and then film the set. Fritz Lang worked with his production team creating a mix of full size buildings, scaled miniatures, and an ingenious use of reflections to create the futuristic world.

The Metropolis team employed a technique devised by Eugene Shuftan, that combined miniature models with real people. A mirror, mounted at 45 degrees, reflected the image of the miniature set that was built behind the camera. When the mirror was scratched away it revealed a see-through panel of glass through which the actors (who were behind the mirror) could then be seen. If everything lined up just right, the camera saw the reflection of the miniature set behind it, while also seeing the real actors acting within it.

It was a clever piece of trickery, totally new at the time, and something that’s also seen in the more modern Grand Budapest Hotel. This time though, rather than using mirrors, the miniature was first filmed, and the actors then placed into the miniature set digitally, a technique known as digital compositing.

To the war room!

Sometimes a place that feels so tangibly real, its walls so strong, its occupants so comfortable, may in fact, not exist at all. The West Wing and House of Cards brought us right inside the White House. They brought us along extensive corridors and into plush presidential offices. As a production designer, it’s up to you to make it believable. But you also have the opportunity to change things. After all, cinema is art. So, what if it wasn’t just a picture here or a chair there that you moved? What if you let your imagination run free? What if the script spoke about a room that didn’t actually exist, but could?

In a position he called “the best role I ever played”, ex Hollywood actor turned President Ronald Reagan should have been more familiar with the tricks of the trade. Cinema, after all, was where he had become famous. But it was on his first day in office that, while touring the White House, he asked his aides to bring him to the war room. “What war room?”, they replied. “The one in the Dr. Strangelove movie”, the President answered in a completely serious tone.

Dr. Strangelove was a Stanley Kubrick movie from the 60’s, and that famous war room didn’t exist. It was a perfectly built set that set designer Ken Adam had taken inspiration from Dr. Caligari and Metropolis to put together. Adams was born in Berlin and trained as an architect in London. His iconic set consisted of an enormous round table lit by a large halo of light, a set which Stephen Spielberg called the best ever designed.

“I don’t know what the government facilities are like,” Adam said. “And I certainly didn’t base the war room on them!” His set is flanked by enormous screens showing world maps for the occupants of the room to analyse, and maybe this is one set you can forgive Reagan for mistaking as real.

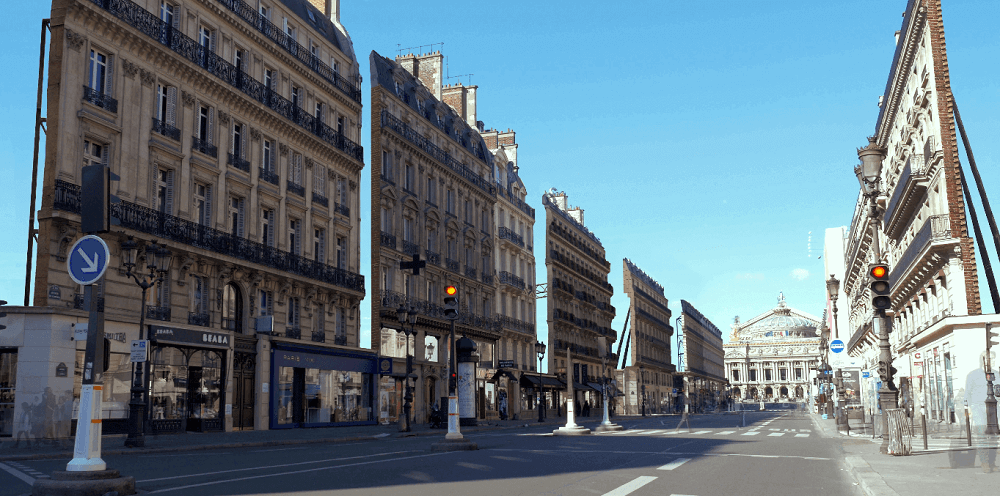

Today, Hollywood fakery has made its way further than just the war room in the White House. Construction sites in China can now be seen with their perimeters walled off with beautifully fake facades, and many construction sites are printing enormous images that cover buildings under construction (Kensington Palace for example). Plus, for a curious look at what Paris would look like as a surreal two-dimensional film set, there’s no better project than that undertaken by Claire and Max of Melimonde.

There are no comments yet