The block construction games are a cultural icon for several generations that have continued to evolve since the first Lego pieces became popular around the middle of the 20th century. Starting with the idea of the original wooden blocks, the Danish company found a way to mass-produce pieces from a strong, colorful material suitable for all ages. Since then, there have been thousands of lines of toys with all sorts of designs for sale. Not long ago, it was calculated that more than 600 billion Lego pieces had been manufactured since they first appeared in toyshops.

Even though Lego fans today build space ships, headquarters for superheroes, or scenes from Lord of the Rings, buildings are still a favorite. At first, they were built from basic pieces by combining blocks of all sizes and colors and looking for the most creative solutions. But their evolution has been spectacular.

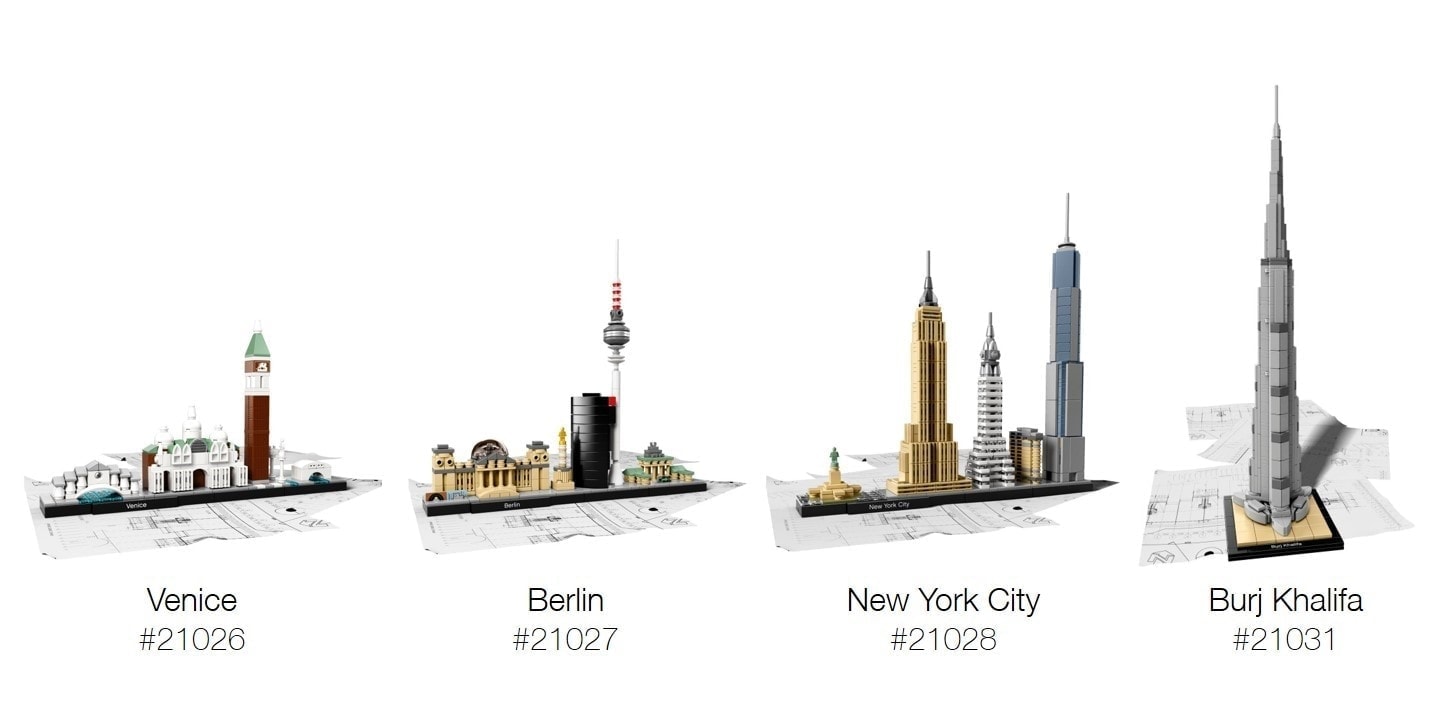

To target the audience who prefers this more technical sort of building, they launched a line called Lego Architecture a few years ago, where they released specific sets of emblematic buildings and monuments from around the world, from the United States Capitol to the Shanghai skyline, and even the Great Wall of China. Additionally, they released a kit called Lego Architecture Studio in collaboration with top architectural studios, which has special white pieces and manuals with specific techniques and advice for architecture enthusiasts.

The power of imagination

But besides choosing the “easy way” with these special kits and themes, there are still those who prefer to let their imaginations run wild and “build the old-fashioned way,” combining pieces of all sorts with a lot of creativity and infinite patience. This is the case for Christophe Pujaletplaa, a fan who has been building an imaginary city and documenting his progress, ideas, and feelings since 2010.

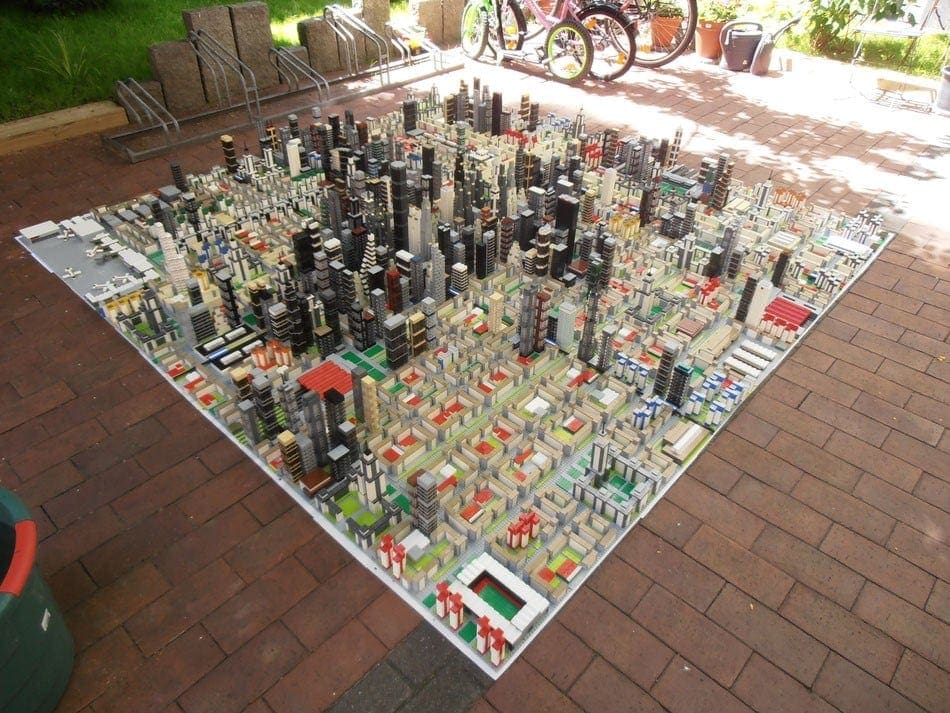

This imaginary city is simply called Microville: my Lego city, and it was born the day its creator rediscovered Lego blocks from his childhood. He decided to build a big city with them, one that was well-planned, with no rush nor pause. He started by making some calculations: at a 1:1000 scale, every Lego millimeter would be the equivalent of a real meter, and the standard 4 x 2 x 1 blocks would be around 30 x 15 x 10 meters, like a small building. The city’s style would be a combination of several real cities: he imagined it to be “a city with a business district like those in the United States, dotted with Soviet skyscrapers and surrounded with North Korean suburbs.”

We can see all this progress on the pages where he posts photos of Microville: buildings, skyscrapers, metro lines… Nothing’s missing. Building started with the preparation of a flat surface made of 16 square gray plates each measuring 40 cm on each side; in 2014, there were already 35 taking up more than 5 square meters, 6 the next year, and a total of 7 m² in 2017, when he presented it at Maker Faire (a fair for makers or fans of building all types of gadgets, inventions, and construction). Currently, it looks intricate and rather labyrinthine.

Planning a city of this sort is no small feat: it requires a budget to buy the pieces – which aren’t exactly cheap– or finding them at secondhand stores, and then matching them with the planned styles and buildings. In Microville, these naturally ended up combining into a brutalist, postmodern architecture with touches of deconstructionism. In the beginning, there were too many clashing colors, which went on merging into something more natural as gray, black, blue, clear, and khaki green pieces arrived. Its creator tore down and rebuilt many of the buildings – particularly their roofs –depending on the availability of pieces and colors at different times.

At the beginning, Microville was basically a collection of streets and buildings, but soon metro lines A, B, and C were added, as well as their stations. Some of the lines snaked between skyscrapers, with 6-car trains. There wasn’t a lot of green space in the city, but it finally arrived in 2016, along with some pools. Organizing the city wasn’t easy, but its creator started to use a numbering system for neighborhoods using different colored plates. The buildings and streets are catalogued and documented in some of the photos, showing the source of inspiration.

Emblematic buildings inspired by real sites also started to appear: skyscrapers like the MetLife building in New York, CTBA’s Torre Cepsa in Madrid, and the Sears Tower in Chicago. The mixture is strange but fascinating at the same time, with details depending on the areas reminiscent of Toulouse, Buenos Aires, Pyongyang, Paris, Moscow, and Barcelona (the Passeig de Gràcia).

Many of the city’s streets and avenues also deserved a name, so generic names like High Street or Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard popped up for the main roads. Microville will probably never by finished, but today it has a City Hall, a national Television building, and an emblematic Grand Hotel. In the last few years, four train stations, a Main Courthouse, a Contemporary Art Museum, the Senate, and – why not? – a few shopping centers have even appeared. A huge labor of love for art, city planning, architecture, and building games.

There are no comments yet