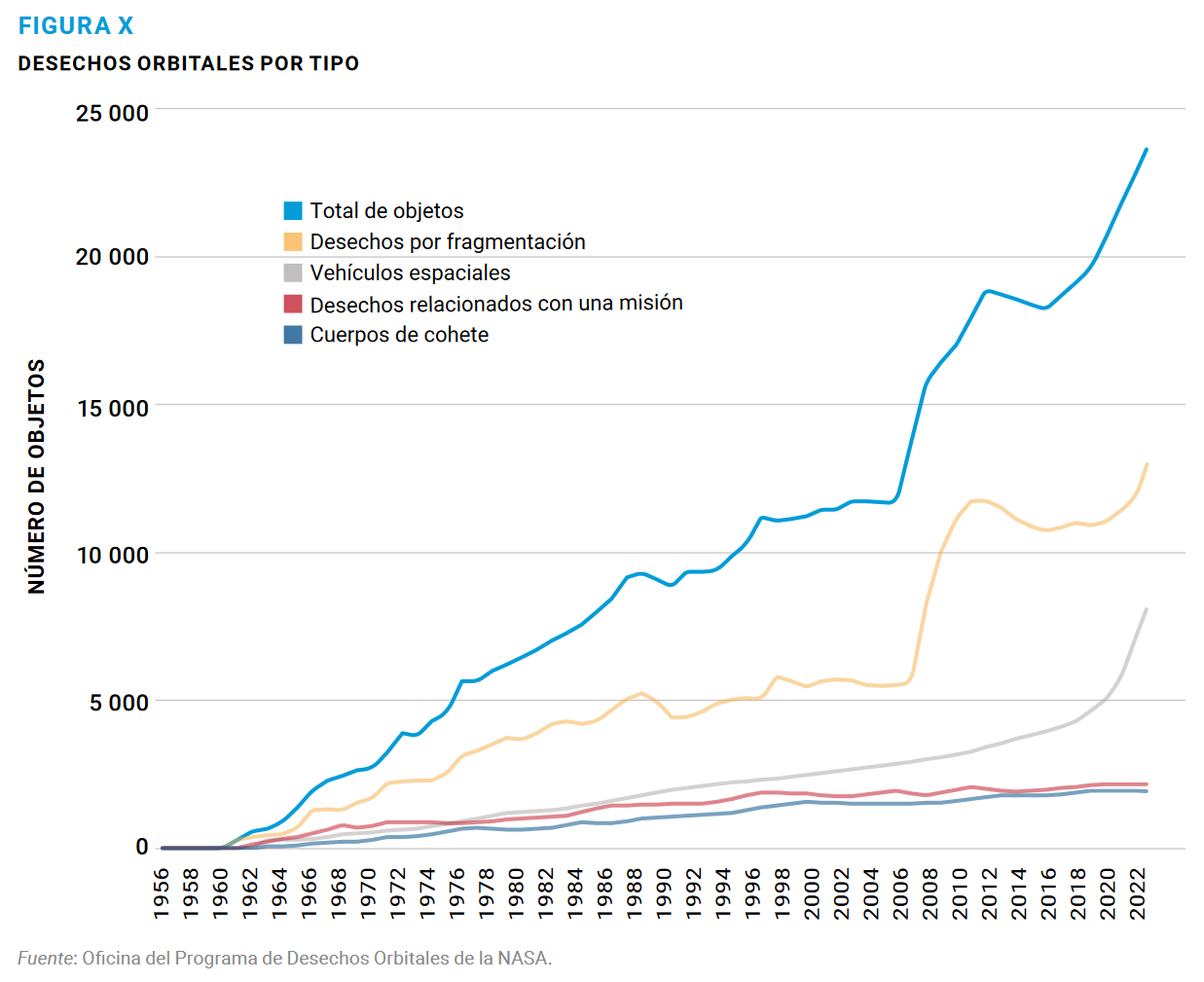

In its 2023 annual report on space debris (data from 2022), the European Space Agency notes that there are approximately 10,705 tons of anthropogenic mass orbiting the planet; the sum total of the 32,540 objects humanity has left behind in space. And that figure is on the rise.

This estimate relates solely to orbiting fragments that are large enough to be monitored. Active satellites, ‘dead’ satellites, remains from old space missions, spent fuel waste and scrap from explosions all surround planet Earth. Tons of waste orbit the planet, trapped in free-fall. How are we going to clean up space?

What is this ‘space trash’ made of?

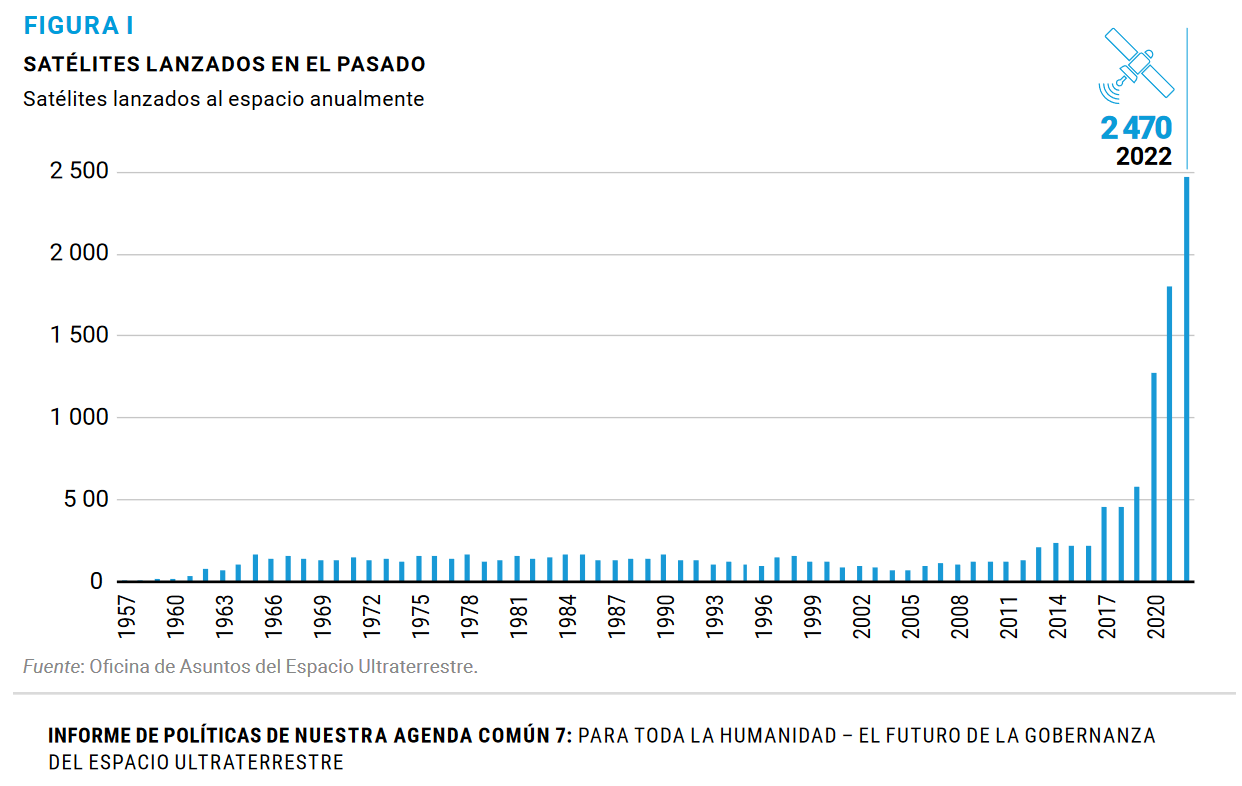

The number of objects in orbit has never been so high. And, as you can see in the following graph, it will have gotten even higher by the time you read this.

Space junk comes from multiple sources. Firstly, there are the loads that are deliberately tossed away; tools that no longer serve a purpose, defunct panels, remains of spacecraft deemed best ejected, waste from missions such as the International Space Station, and so on. And then there are the missions into space that have reached their end – these components simply continue to orbit the planet; inert, waiting for Earth’s gravitational pull to engulf or throw them deep into space.

The third type of space junk comes from ‘fragmentation events’; a rather elegant way of describing an object dividing into several smaller objects, stemming from a variety of scenarios including meteoroid collisions, military anti-satellite tests, accidental explosions, fuel residues (which freeze into solid matter), etc. The ESA data tells a fascinating story, estimating some 900,000 fragments measuring more than one centimeter are out there somewhere, all too small for us to know precisely where they are.

Kessler syndrome: humanity trapped on Earth?

The space waste conundrum goes beyond environmental practices or protecting space so that we can observe the universe. In 1991, NASA consultant Donald J. Kessler published a scientific article entitled ‘Collisional cascading: The limits of population growth in low earth orbit’. This paper pointed to an unavoidable truth: the more matter there is orbiting the planet, the more the likelihood increases of a chain reaction of explosions and collisions, in turn causing further explosions and collisions. In fact, this idea wasn’t new. In 1960, Willy Ley had already demonstrated that once a certain amount of space waste was orbiting Earth, we would need to remove the junk to make space for new launches.

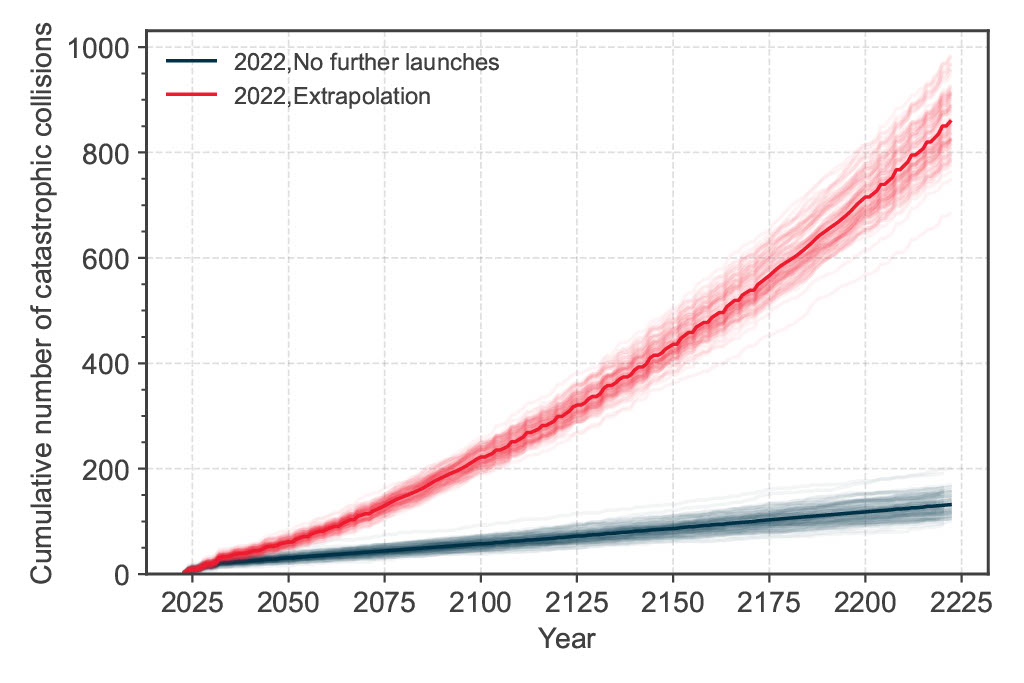

You need only look at one example to understand the problem. When a small object collides with a one-ton satellite, the likelihood of the latter exploding – converting the whole mass into hundreds or thousands of small fragments of shrapnel – skyrockets. And this kicks off the process once again. None other than the ESA and NASA openly acknowledge that the number of catastrophic collisions will only rise in the coming decades, even if we stop launching objects into the orbit (blue line below). That’s just the matter that’s already out there. And if we continue to do so (that’s the red line), the increase will be remarkable.

This is known as the Kessler syndrome; a phenomenon that could leave humanity stranded on Earth for centuries: if a chain reaction of collisions and shrapnel occurs before we’ve deployed the right technology to clean up the orbits, it simply won’t be possible to deploy the technology. And this means we won’t be able to enter or leave the planet safely, because every new attempt would produce even more debris.

Space is unregulated, so who will regulate it? The regulator that…

One of the biggest challenges in space is the lack of specific regulations that assign responsibilities to companies and even individuals (the mega-rich, at present) or make it possible to have accountability. The waste on the surface of our planet is indeed regulated, and more and more companies are being asked to take charge of their waste externalities. Meanwhile, space (or ‘outer space’ to use the international legal term) is the Wild West. The ‘Space Sustainability report‘ lays it all out.

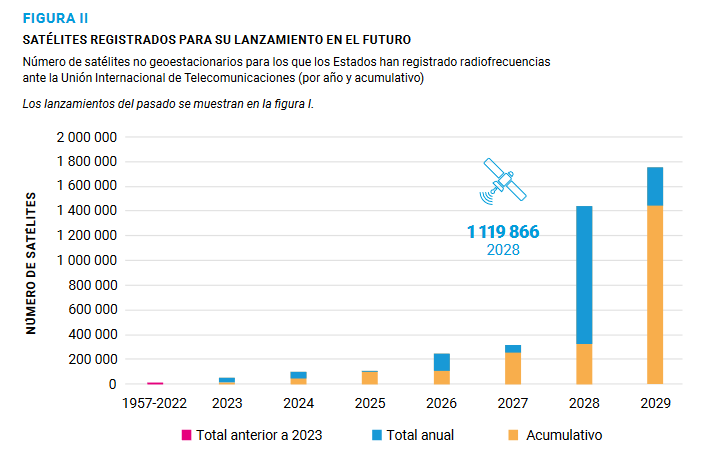

As stated in the recently published UN report ‘For All Humanity – the Future of Outer Space Governance‘, there are indeed frameworks between countries that “have served the international community well, in preventing conflict in outer space and facilitating safe and sustainable space activities”. Challenges in terms of space traffic coordination are becoming increasingly complex, and there is a lack of consensus on how to solve some issues. The concern is that excess waste will make it impossible to use satellites from now to hundreds of years in the future.

Solving the space junk conundrum

Recommendations from the Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space include increasing the transparency of countries, creating protocols and governance frameworks, and improved management of space traffic, with a particular focus on getting rid of space junk, or removing disused debris from space. The solutions include:

- Waste mitigation. Here on the Earth’s surface we talk about the three Rs, with ‘reduction’ being a strategy way ahead of ‘reuse’ and ‘recycle’. And it’s no different in space. The ESA Mitigation Requirements and Inmarsat recommend reducing the number of satellites sent into orbit.

- Orbital-use fees. Based on the premise that space is a common resource, charging for its use should, paradoxically, increase the value of the space industry by increasing the durability of satellites that do not collide with other remains. Less debris means longer missions. Orbital-use fees would be charged per the occupancy of the orbit: more saturated orbits would have higher rates.

- Space cleaning brigades. Missions such as the ESA’s ClearSpace aim to remove debris from orbit. Imagine a waste-hunting satellite that propels other satellites into the atmosphere to disintegrate into the same; something not without its own controversy, due to its polluting impact on the planet.

- Space-debris nets. Successful experiments to catch satellites with nets have already been carried out; think of it akin to fishing in outer space. Literally, fishing nets. Used to change the orbit of satellites. This technology certainly has its limitations, but work is going in the right direction.

- Debris-zapping lasers. Though it might seem beyond the realms of possibility, it has been demonstrated that it’s possible to propel orbital fragments into space using light from Earth, creating a thin layer of plasma on the satellite. The idea is to use laser pulses (from the Izaña-1 station in Tenerife or Monte Stromlo Observatory in Australia) to nudge debris off course.

There are no comments yet