Mendoza, the oasis city with an irrigation system rooted in pre-Columbian orchards

15 of October of 2024

Rain is a rare sight in the city of Mendoza, located in the west of Argentina at the foot of the immense Andes mountains. Precipitation graces fewer than 60 days a year, and generally in summer when the heat bursts into storms. In spite of it all, this conurbation is known by its nickname ‘the oasis city’ for good reason: flanked by desert in all directions, it boasts a wealth of trees and green spaces.

Behind the lush vegetation in Mendoza lies more than successful urban policies. It also features an irrigation system that still drinks from canals used by the Huarpe people—and probably the Incas—before the first Spanish colonists landed.

The history of a city oasis

Mendoza was a finalist of the 2024 FAO Green Cities Award, given to cities that create and maintain green spaces to improve their climate-change resilience, social cohesion and economic stability. The FAO highlighted innovation in Mendoza’s governance—including its digital platform and residents’ participation in urban forest management projects and policies.

Used to tackle environmental and social challenges, Mendoza’s innovative governance system is closely linked to the interests of citizens themselves and is based on preserving the green spaces fundamental to the town’s history and character.

When Spanish colonists first came to this Argentinian region, they took advantage of the irrigation systems devised by the native Huarpe people for everyday use and crop irrigation. The system harnessed the powers of the sloping land, creating a complex network of canals and channels that distributed water throughout the land.

Whilst there is an absence of written records, the oral history tells how the Incas helped the Huarpes to perfect their water system. According to this theory, the Incas adapted their then-perfected terrace cultivation method to the topography and orography of what is now Mendoza.

Highway in the province of Mendoza stretching across arid land beyond the city. Gustavo Zambelli (Unsplash)

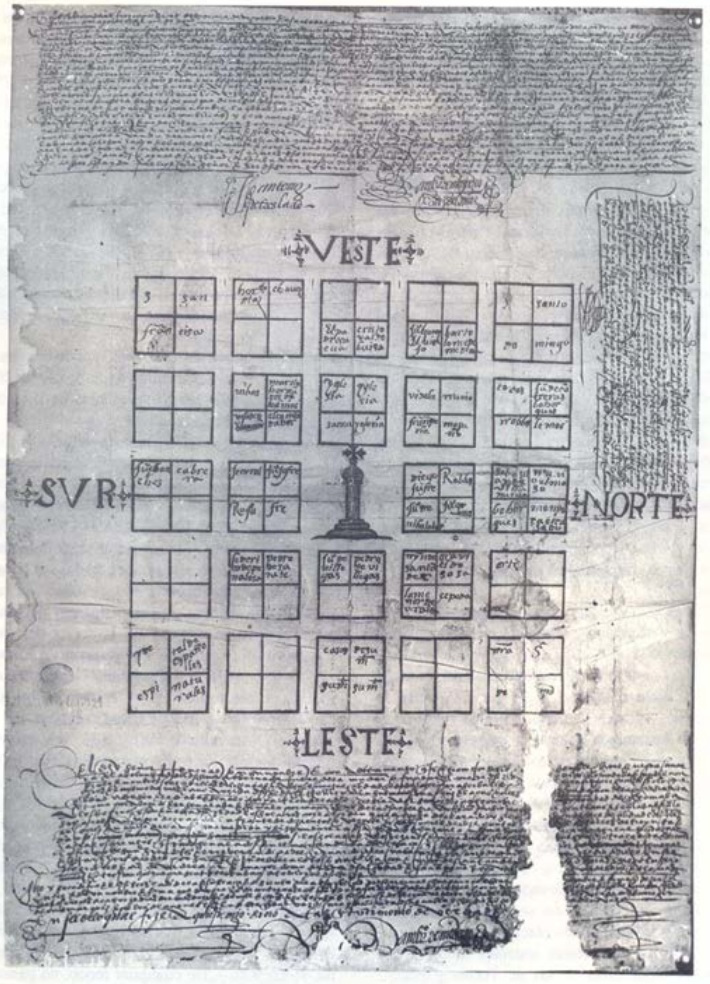

The Spanish people who founded Mendoza in the 1560s modelled the city in the same format as so many other colonial cities. The objective? To defend themselves and promote progress in conquering new territories. A large central square—the ‘Plaza de Armas’—would be created with sufficient space for army exercises, public buildings and a market.

Foundational plan of the city, now Mendoza, from 1562. Wikimedia Commons.

The city’s inhabitants maintained an ingenious system of irrigation channels to ensure a water supply in an enclave surrounded by desert with an arid climate. These channels crossed the new streets, directed by the natural slope of the land. This provided enough water for human consumption as well as watering their orchards.

Mendoza trees after the earthquake

Over decades and centuries, the trees growing alongside these irrigation systems gave shape and character to Mendoza’s public spaces. Chroniclers and travelers who came to the Argentinian city told of the bountiful vegetation, both on the streets and in private properties where plants and fruit trees flourished.

In 1861, a major earthquake forced a restructuring of Mendoza. Planners opted for a highly orderly grid system with wide streets and numerous channeling projects. From then (the latter half of the nineteenth century), green spaces and irrigation channels (as well as aesthetics and public health) became a fully integrated element of urban planning.

The irrigation systems inherited from the Huarpe people transformed the Mendoza landscape, and the concept of maintaining an oasis city brimming with exotic vegetation in a semidesert landscape gained ground.

An irrigation system for trees in the present. Pablo BD (Flickr)

The irrigation system had a dual function—supplying drinking water and irrigation—until the end of the nineteenth century. This was the advent of modern piping when the two functions became separate. Today, the irrigation channels in the streets of Mendoza (subjected to several overhauls over the centuries) are the basis of a unique water system, and a cultural and historical heritage that the city hopes to preserve.

The future of a centennial system

In 2001, more than one tree per inhabitant was added to the metropolitan area of Mendoza. The green spaces and irrigation system generate numerous benefits for the city and its inhabitants: they mitigate the so-called ‘heat island effect’ (which heats up urban areas at night when materials like asphalt release all the day’s accumulated heat), increase the level of moisture in the air and reduce temperatures, representing significant energy savings in the hottest months of the year.

Canal in Mendoza. ActiveSteve (Wikimedia Commons)

What’s more, the green spaces make for a more aesthetically appealing urban space, improve social cohesion and considerably enhance citizens’ physical and mental health. One of Mendoza’s challenges in the present is to ensure the entire system that created this city oasis—maintained and perfected over centuries—can cope with the scarcity of resources triggered by climate change.

There are no comments yet