Constant's New Babylon: a work-free city made an art-world reality

20 of November of 2024

In a place still suffering the consequences of two world wars in the 1950s, Dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhuys embarked on an artistic project conceiving a new urban environment. A city he sometimes—though not always—wanted to be utopian. He baptized it New Babylon.

In Constant’s imagined future all work would be done by machines, leaving citizens with lives devoted to rest, revelry and creativity. In this new urban landscape, architectural elements would be designed to promote an egalitarian, borderless world.

A futuristic utopia

The idea of creating New Babylon arose in 1956 when Constant (an artist always known by his first name rather than his surname) visited a group of nomadic gypsy families that had settled on the outskirts of the Italian city of Alba. For Constant, the trip was an opportunity to design plans for the creation of an encampment. But the concept he returned with would go on to shape his artistic path for the next 20 years.

The families’ nomadic, creative and free lifestyles caused him to reflect on other ways of life, and the potential to create a city in which private property no longer existed. He began his work on New Babylon. Whether you saw it as an urban theory, imaginary society or simply a representation of a utopian lifestyle all depended on the lens through which you looked.

As Constant described it, New Babylon society was a place where technological advances meant citizens would no longer have to deal with mundane tasks like cleaning, cooking or manufacturing objects. These would all be automated. The extra time would leave people to fill their lives with creativity and enjoyment.

Image of an exhibition of Constant’s work at the Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofía. Photo by Joaquín Cortes/Román Lores

In this new reality, citizens would be unshackled, no longer tied to a specific place. Private property would be a thing of the past. They would be nomadic, wandering the world in search of forming new bonds. Another key feature of Constant’s new society was the disappearance of social class and all distinction between rich and poor. Travel and enjoyment of spaces would be open equally to all.

New Babylon is considered one of the great utopias of European art. Nowadays, even the straightforward idea that machines would achieve equality feels somewhat unrealistic, but in optimism was in the air back in 1950: after the ravages of two world wars, echoes of the need to conceive a better world were getting louder in political, social and cultural spheres.

And artists—like architects and urban planners—were all doing their bit to bolster this optimism. The aftermath of the Second World War prompted the imagining of a better world, through art and a number of other disciplines.

The architecture of New Babylon

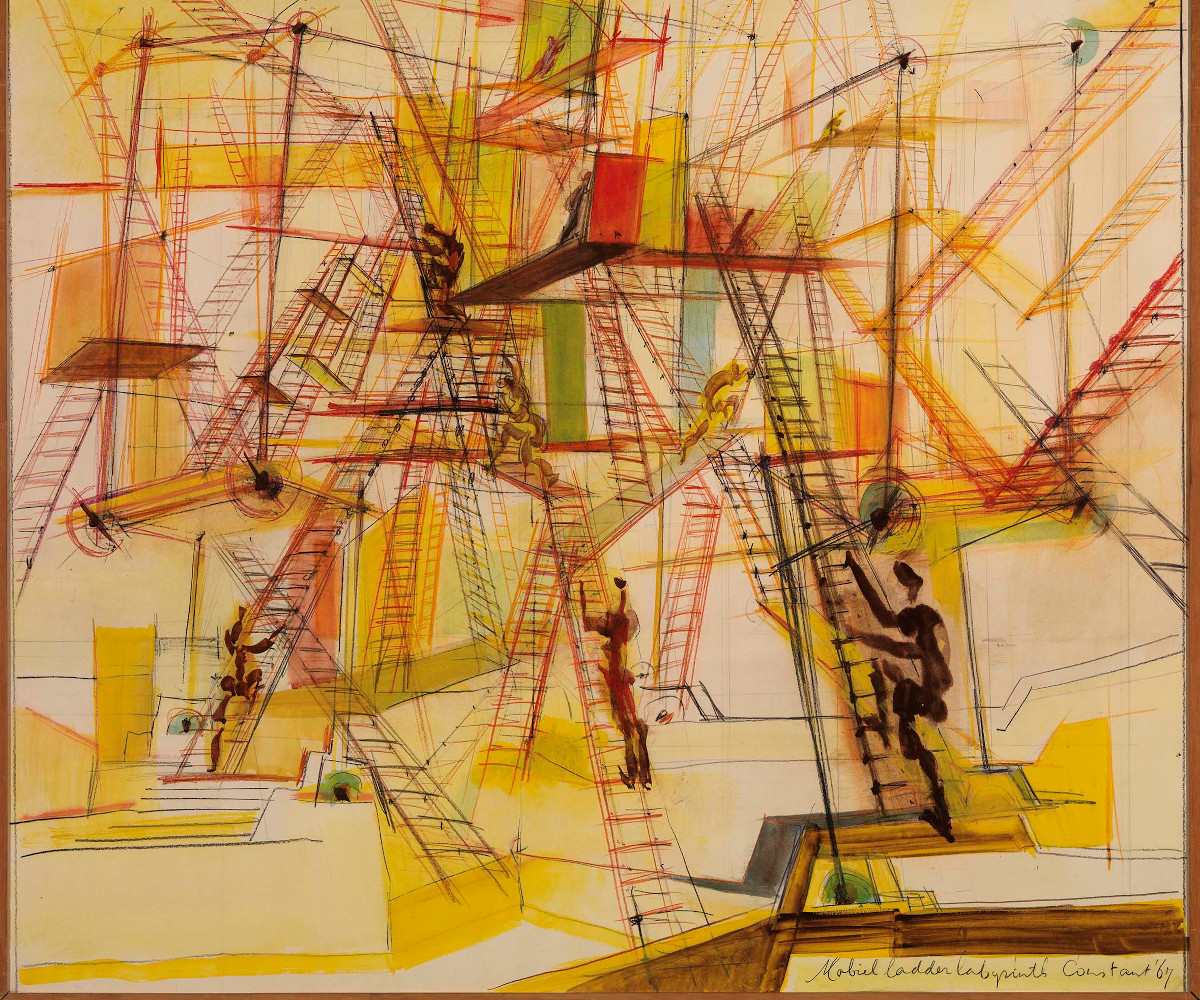

In New Babylon, traditional architecture has disappeared—along with society as we know it. “New Babylon is a gigantic labyrinthine complex raised above the earth on tall pillars. All forms of transport circulate below it. The various tiers of the city can be reached via lifts and stairs and are almost entirely roofed-in and climate-controlled”, wrote Constant.

As Constant’s imagination saw it, the floors of New Babylon would be transparent, and the nomads themselves could spontaneously control and reconfigure elements, changing the look of the environment. The various spaces would have light and sound effects offering a different lived experience at any given time.

‘Mobile Ladder Labyrinth’. Constant’s illustration of New Babylon. Gemeentemusem Den Haag/Museo Nacional de Arte Reina Sofía

His work involved elements normally seen in science fiction stories: platforms suspended over the ruins of previous civilizations, buildings constantly being reconfigured or crafts gliding beneath dwellings, taking people straight to their homes.

Constant’s goal was that this broad network of spaces would spread anarchically until the whole planet was covered, completely free of borders. Every one of Constant’s innumerable works on New Babylon (he created models, drawings, collages, prints, watercolors, conferences presentations… even films) gave shape to unitary and egalitarian urban planning, in which profits and class differences were no more.

His influence on urban planning and architecture

The New Babylon project was first exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1959. While it received little success, nor the attention given to other urban planning projects, it’s nonetheless believed that his work had a significant influence on architects reflecting on the emotional and social impact of buildings and cities, such as Zaha Hadid and Frank Gehry.

Photo of Constant next to his models. Noord-Hollands Archief, collectie Fotopersbureau De Boer. Wikimedia Commons.

Over time, Constant’s perspective and his city ideal gradually shifted. His work, like his philosophy, was changing. He began to examine concepts of anti-capitalism, the anti-bourgeois struggle, collective creativity, and a theme that has preoccupied generations of artists: the role of art in creating a better world.

There are no comments yet