All too often, rusty subjects try to make certain historical heritage their own, sweeping all knowledge into their own coffers. “This is architecture” or “This is culture” is, today, an altogether too simplistic way of classifying the beauty we conserve from the past, as if it had been created with tags.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Today we will talk about theatres, their evolution over the course of history – the evolution of architecture – and what they say about the architecture of their time. Because these two subjects – theatre and architecture –, have had more links between them and have needed each other more than we might initially believe.

Greek theatre: the gods have something to say

Theatres were for many centuries the best example of mass culture. In ancient times they were the equivalent of our television or streaming. The first theatres did not put on performances for a few, but rather transmitted the words of the gods (who were very prolific in Greek times) to the more people the better.

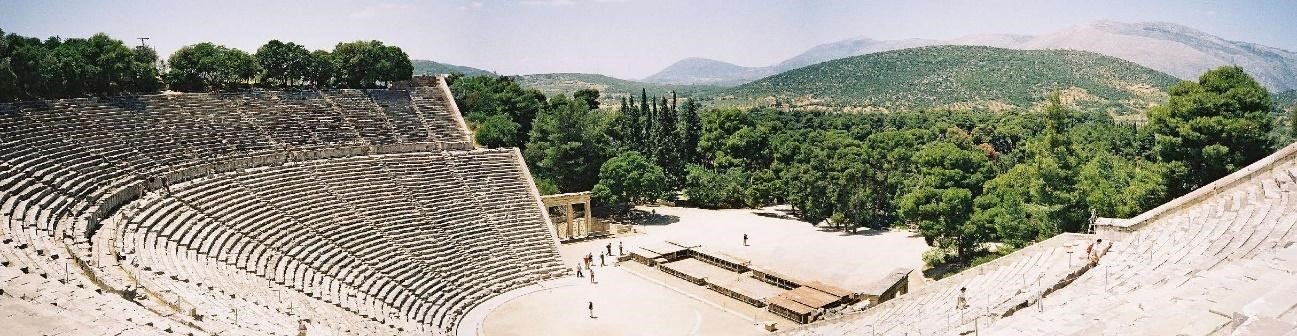

View of the orchestra (circular plan at the bottom of the slope) of the Theatre of Epidaurus from the upper seating area. Source: Gonzalo Serrano Espada

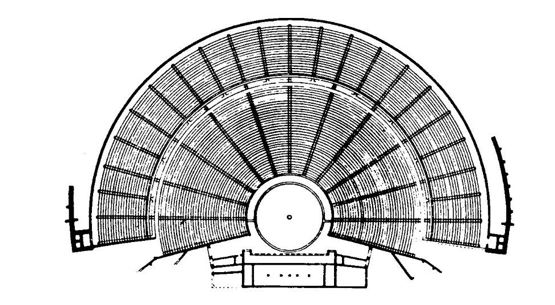

Initially there was a lack of spaces where large numbers of people could listen to the words in the chants, and so very soon large flat or cone-shaped esplanades started to appear, where you could sit and watch the performances. For some time they were not very different from the circles or semicircles formed when you sit on the ground at a camp, for example, but it soon became obvious that these spaces were not enough to hold all the spectators.

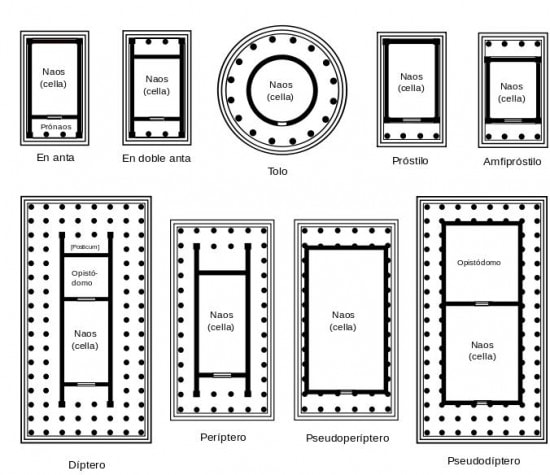

Plans of various types of Greek temples. Narrow and with walls everywhere, it was fairly complicated to represent plays inside. Source: Bojan Jankoloski

An alternative option could have been the temples, but the limited space available between all the walls and columns these had – as a result of a not-too-advanced construction technique and limited knowledge regarding the behaviour of the materials used – meant that slabs of stone were soon being placed over the esplanades. Using the slopes to make seating, it was not long before the Greek theatre emerged.

Despite the simplicity of their design, they already had components which are still recognisable today, such as rows of seats (koilon), inner walkways (scale for the vertical ones and diapsoma for horizontal circular ones), stage (orchestra) and decorative elements (skené). However, a direct equivalent for certain of these components is somewhat difficult to establish given how theatre has evolved over time.

For example, Greek decorative elements were little more than a narrow building several storeys in height, from which were hung cloths or simple atrezzos, a far cry from modern productions where the stage undergoes veritable transformations. Moreover, the orchestra area was initially for both the instruments and the actors themselves.

The Roman theatre: people also voice opinions (though not much)

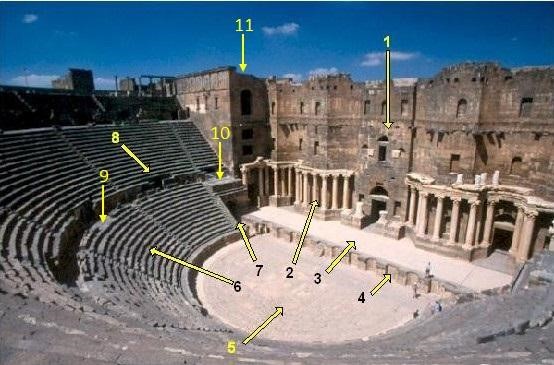

The Roman theatre hardly added to or removed any of the elements used by the Greeks, probably because their architectural technology had not evolved sufficiently to stand out from them. What they did do was separate the orchestra, which became a pit, from the proscaenium, which would become the stage.

Roman theatre in Bosra (Syria). (1) Scaenae frons (2) Columnatio (3) Proscaenium (4) Pulpitum (5) Orchestra (6) Cavea (7) Aditus maximus (8) Vomitoria (9) Praecinctio (10) Tribunal (11) Basilica (see Roman theatre/structure). Source: Joris.

A better understanding of physical acoustics brought about slight changes in the slope and in the separations, making theatres slightly bigger. As the doctrine of the gods waned in importance and gave rise to mythology (and later human stories), the stage started to fill up with columns, until there were two or three rows (seen more clearly in the photograph in front of the scaenae frons).

Towards the end of the Roman period, performances at theatres were more about human stories than divine ones. Tragedies, comedies, satire, political critique, mime, farce... Theatrical culture became ever richer over the centuries as walls became thicker and constructions more permanent.

But then the lights went out on European culture…

Oriental theatre: listening to the flexibility of nature

Luckily, the spark of knowledge was still burning bright in another part of the world, while the Mediterranean suffered the devastation of religious wars. As opposed to the Greek gods, these Gods with a capital G were not brothers and sisters, and their followers fought in battles which drove back culture at the swish of a sword.

In India (Hinduism), in Japan (Zionism) and in China (Buddhism), this culture manifested itself with songs, dance and mime. This is not to say their peoples did not subsequently go out and fight neighbouring villages, but such was their respect for the performing arts that they were always maintained as part of their culture.

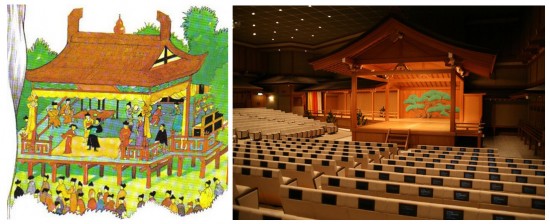

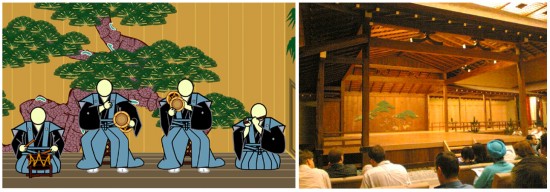

Almost all oriental theatres have the same quadrilateral shape, about six to seven metres wide, ever since the first Chinese theatres of the 2nd century BC. The pictures show the nō (noh) Japanese theatre from the 14th century, easily recognisable by the decorated back wall and the four wooden pillars making up the stage.

Given the close ties oriental peoples had to nature, most of the theatres (and practically all buildings) were made of wood and other plant materials. The flexibility and mechanical behaviour of these materials allowed them to shape stages in ways that neither the Greeks nor the Romans were able to do, although it also meant that they have not survived the passage of the centuries quite so well.

The scenic arts contained in these small temples, unlike in the West, did not require sophisticated decorative elements other than the costumes themselves. Even today, the mahanataka, dutangada and kathakali Hindu disciplines, kunqu and the Chinese theatre of shadows, or the Japanese Nō and kabuki seem minimalistic to Western eyes inasmuch as architectural and structural elements are concerned, with the skills of the actors being the only feature required.

Medieval theatre: the theatre of the guerrillas

It is interesting to see how theatre the world over took a great leap forward into the 14th century (including most of the oriental styles mentioned in the previous paragraph and medieval theatre in Europe), yet how these styles and the architecture of theatres began to differ over time. In Europe, in fact, architecture and theatre moved apart in the dark centuries of the middle ages.

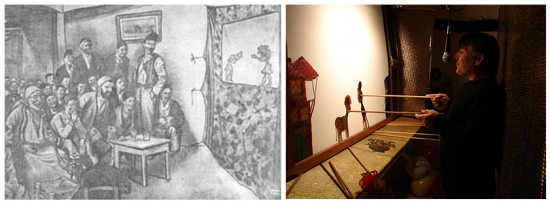

Representation of Karagöz and Hacivat shadow plays, precursor of puppet theatre (14th century in Turkey), and a modern representation.

In a historical context of Church feudalism in which the arts were deemed profane, science necromancy and culture undesirable, there was little space for theatre and other non-religious arts. And so theatre split into two main categories:

- a theatre that was allowed and socially accepted, which paraded down narrow city streets, and which evolved down the years into our modern brotherhoods and romerías (religious pilgrimage processions), amongst others;

- and a theatre that was banned (but nevertheless also socially accepted) and which we have come to know today as puppet shows.

However, banned or not, both were guerrilla theatres. Whilst monotheistic churches (albeit only those that practised idolatry) tried to convince the faithful with grand religious processions representing biblical scenes, puppets and puppet shows represented leisure and a critique of the system.

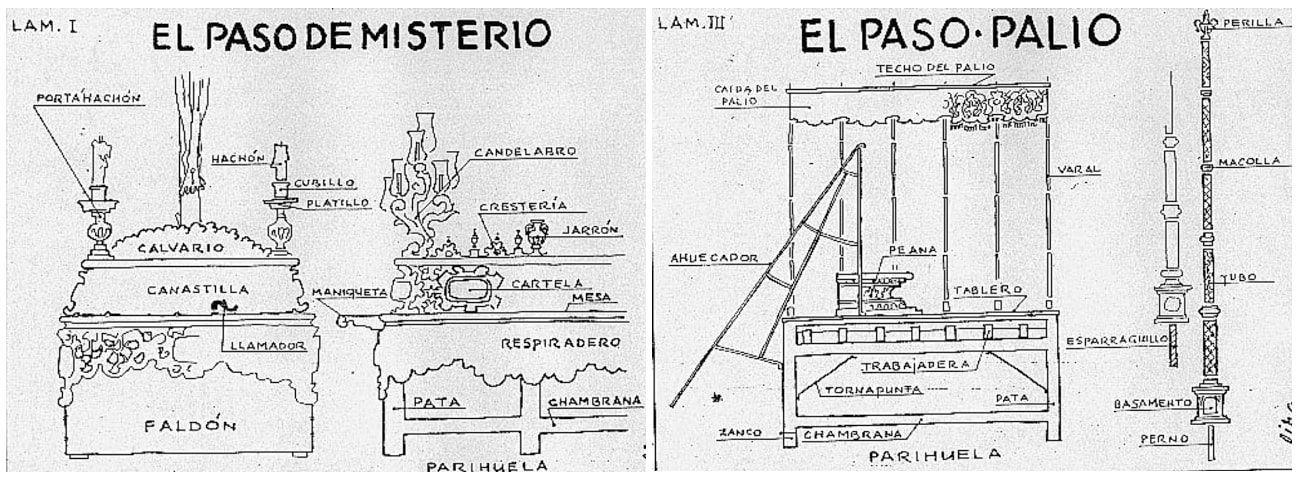

Drawings I and III showing the engineering required in the Easter Week religious representations or “pasos”. Source: Imaginería andaluza

But despite lacking a formal structural architecture (a proper building or theatre), structures were of crucial importance for the two sides.

Puppet shows had to adapt to include complex pulley and other systems for moving the wood and cloth puppets around the small stage (and to be able to quickly hide it all in a matter of minutes), whilst the structural complexity of religious representations meant that engineers had to carefully design the wooden support structures.

As the popular masses received their required dose of culture on the streets, only a select few were able to enjoy “castle theatre” under a roof. Here, classical works from popular or religious traditions were represented, for the first time using systems for changing the stage scenery during the performance itself, as in the castle at Český Krumlov.

Whilst oriental theatre focused its efforts on the appearance of the actors, in Europe the focus was on complex side pulley systems which gave rise to our modern systems (making it necessary to have purpose-built theatres, rather than using reconverted buildings).

The modern theatre: a theatre for each social class

Towards the end of the middle ages, open-air theatres (called corralas in Spain) started to appear in Europe, first in the courtyards of existing houses, and later on in purpose-built settings. These were low, three-storey buildings in which a small stage could be viewed from the balconies and a seating area in the courtyard itself.

Open-air theatre (corral de comedias, or comedy theatre) of Almagro, the only one in Spain which has been conserved as it was in the 17th century. Source: Educa Madrid

These buildings bring back many of the elements present in Roman theatres, such as a pit for the orchestra, the stage, the semi-circular setting (now cut at the sides in modernist construction), or the front access of performers onto the stage.

These open-air theatres put on performances for poorer citizens (as opposed to the theatre performances at the palace for the Court) with plays which were no longer in Latin but were very critical of the monarchy or other government systems. But when the rich bourgeoisie started emerging in Europe, a third type of theatre became necessary, and this is very similar to what exists today.

Theatres today: a synthesis of the history of architecture

Towards the end of the modernist period, theatres already comprised the elements we are used to seeing today and which are all part of Greek, Roman, oriental and medieval legacies. There is a distinct separation between the public in the stalls, stands and boxes at different heights (on the sides and to the front), and the stage and orchestra.

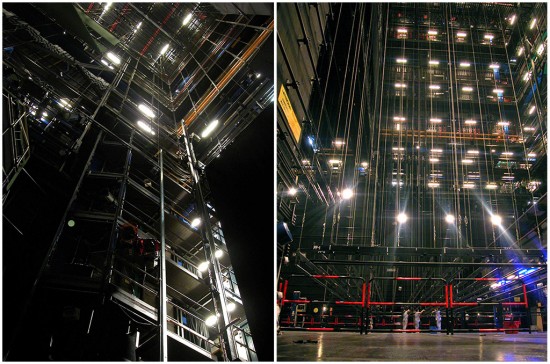

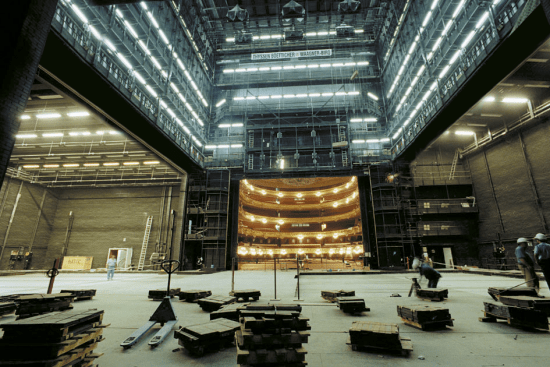

But today’s theatres focus on areas which are not visible to the spectator, such as the wings, the pit below the stage, and the pulley system and drop scenes above it. The purpose of all of these is to make the scene more realistic, and this requires large amounts of space around the stage in all directions.

As I said in the opening paragraphs of this article, the differences between the various subjects work hand in hand today. For today we cannot say that theatre is part of the scenic arts, or that the building is part of architecture. If we did, where would the necessary mechanical, electrical or electronic engineering stand? Or the plastic arts required for the stage décor? Or the project management and coordination for each performance, or the effort of all the people involved?

Can we separate each subject into its own little box, or is it better to enjoy it all as a whole?

There are no comments yet