When we hear the word road we imagine strips of asphalt bordered by low walls or metal barriers, with white-painted lanes and road signs to help keep us safe.

However, there are some places in the world with roads that have never seen this product, and instead have roads with asphalt alternatives. Hard ice, crystallised salt, earth or dunes are some of the building materials used to accompany the few vehicles that use them. Seat belts on, it’s going to be a rough ride!

Roads of hard ice and compacted snow

If we’d been asked a few years back, few of us would have been able to explain what winter roads were, that well-kept secret of daredevil lorry drivers who drive across frozen lakes and rivers during the winter months. Roads which can be as much as eight motorway lanes wide.

The TV series Ice Road Truckers started in 2007, making the world aware for the first time of the dangers of these roads. Ten seasons on, the series has been an absolute success.

Rather than being a regular highway, road or path, winter roads, frozen roads or temporary roads are simply routes that are usable two, three or four months in the winter depending on the latitude. They appear (given that they are not actually built) in bleak, desolate landscapes, such as parts of northern Alaska, Canada, Russia, the north of China, Scandinavia, Estonia and Sweden, as the winter sets in.

The “road” surface varies depending on the time of year and the place, and this dictates the type of vehicle that can be used. In the summer, when the ground surface or permafrost hardens, small cars and vans can drive over some areas.

However, the difficulties begin with the onset of the cold winter temperatures, when the rivers and lakes start to freeze up. So much so, that lorries weighing up to 40 or 60 tonnes can drive over them.

Anyone who has stepped on a frozen puddle only to see the ice crack and break up into hundreds of shards, their boots plunging all the way down to the bottom, will appreciate how dangerous it is to drive on these roads. Or how thick the ice must be to hold a 60-tonne lorry.

However, nature is amazing; and thick ice a material that is incredibly resistant to compression, and able to create a road in little more than a week. Building the same road using traditional methods such as asphalt takes many times that. And, in some places, it is impossible.

Part of the danger of these roads comes from the speed of the lorries and their weight. Many times, they may go no faster than 25 km/h, covering only 200km in eight hours.

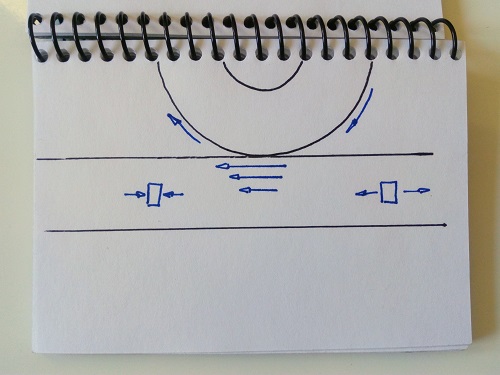

The above drawing shows how, when the wheel turns at high speeds, the layer of ice underneath tends to gain momentum in the opposite direction to that in which the lorry is driving. This compresses the area behind the wheel and breaks the ice through compression. The area in front of the wheel stretches and cracks through traction. If a lorry speeds up and manages to break the ice both in front of and behind the wheels, the ice sheet could become unstable and turn on itself.

The Tuktoyaktuk road shown in the two photos is neither the only one nor the most famous. Hay River, Yellowknife, Ingraham, the Tibbit to Contwoyto road… where there’s a place needing material to be delivered or picked-up, lorries will get there in the winter.

These routes don’t appear on any map. If you were to land softly on the ground captured by the satellite and look around the area, you would quickly notice the complete lack of infrastructures there. These roads are surrounded by nature, and built by nature.

Crystallised salt roads

Driving on the frozen ice of rivers and lakes is dangerous, but driving on salt desert roads (if, indeed, they can be called roads) is no less so.

There are five salt deserts in the world big enough to stretch into infinity, their limit being well beyond the horizon: Uyuni, in Bolivia; Salinas Grandes, in Argentina; Atacama, in Chile; Bonneville Salt Flats, in the USA; and Etosha, in Namibia.

These salt flats all share common characteristics that make the routes across them a challenge: they stretch away in all directions, with no end in sight. Great photographs (who wouldn’t enjoy the spectacular skylines shown below?), but these deserts pose a massive challenge to any vehicle at any time of the year.

During the hot months, this never-ending surface of crystallised salt doesn’t reflect the clouds. Although in deserts such as the Salar de Uyuni the ground temperature doesn’t get very high, the fragmented plates of salt crystals are dangerous for the tyres of the vehicles driving over these improvised roads. To be stranded without water in the middle of a desert is as dangerous as it sounds.

However, other deserts, like the Atacama, combine these salt potholes with temperatures of 50ºC in the shade, making driving rather uncomfortable. An infinity of salty dips in the ground with the texture of compressed earth. In addition to the continuous potholes there is the problem of tyres skidding every few meters as the salt crusts crack and give way under the weight of the vehicle.

If driving during the summer is hard, travelling on these routes in the winter, during the rainy months, is even worse. You won’t get a flat tyre from crystallised salt hardened by the sun, but the persistent layer of water that softens the terrain will make it impossible to drive anything but a four-wheel car.

Added to that, the absence of visual references (with the exception of Isla Incahuasi, Fish Island or other similar hillocks which help us distinguish earth from sky) makes orientation next to impossible. The landscape appears endless, and it’s difficult to locate the horizon with any degree of certainty, and even harder to guess direction.

Roads of earth and sand

Bordering many of these very salty areas are some of the world’s deserts, a delight for any photographer and a good testing ground for competition vehicles. The Moon Valley (Valle de la Luna), in Atacama, is one of these.

Here, many of the roads are made over time as the scarce local and tourist traffic carves them into the landscape. In much the same way as wind and rain does with rocks, vehicles create paths by driving time and again over the same areas, gradually grinding the compact sand into the ground.

Similar earth roads appear in any other dry, desert areas throughout the world, particularly in the warm strip joining Morocco and Mauritania with Yemen and extending all the way to New Delhi, in the north of India.

Sand dunes often spill onto these tracks, covering the route for several seasons until it reappears years later, when car tracks again carve another road into the hard ground.

In sandy deserts, all trace of any road disappears a few days after a vehicle has passed. The wind and the lightness of the sand are responsible for this, making not only the building of an asphalt road difficult, but also the marking of routes of any type. Signs are simply swallowed up by the dunes.

We are so used to having roads linking nearby locations, that we are often unaware that there are places in the world where the roads aren’t permanent. Or where road conditions differ so much from one season of the year to another that there are times when it simply isn’t possible to use them.

Far from being built artificially with materials such as cement or asphalt, we are lucky that these roads spring from nature. If they didn’t, many parts of the world would be completely inaccessible.

There are no comments yet