The language spoken only in control towers to manage a sky-load of planes

12 of December of 2017

A lot of talking goes on in control towers: an air traffic controllers job revolves around communications between tower and pilots. And not exactly via WhatsApp: communication is essentially via radio and speech.

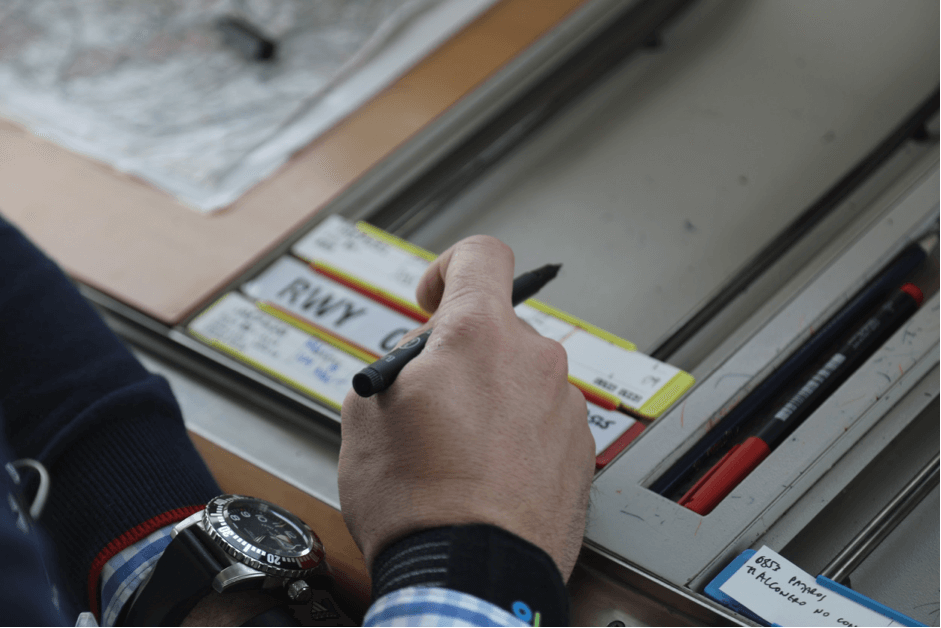

But within the cab (the area where air traffic controllers work), communications between them are very different. They are generally carried out in silence, with flight progress strips containing only the information required for carrying out the tower’s basic function: that of making planes take off, fly and land in maximum safety.

However, if we think about communications between controllers and pilots, we have a whole host of questions. What language is used for communicating? What are conversations between tower and aircraft like? What rules must be followed when giving instructions?

An aeroplane is a means of transport which, when approaching an airport, moves at speeds of between 250km/h and 400km/h. When flying at a height of 10.000 metres, that speed reaches 800km/h or 900km/h. At such speeds, any overly long communication could mean missing vital time windows during take-off and landing procedures. Just to get in the picture: it takes 12 seconds to cover one kilometre at 300km/h.

Taking into consideration that there can be dozens of planes in the proximity of an airport, with all of them undertaking take-off and landing operations, the situation can get pretty complicated.

If a plane doesn’t carry out landing, taxiing, parking, taking-off or any other manoeuvres correctly, in a situation of continuous traffic reaction times are reduced to a minimum.

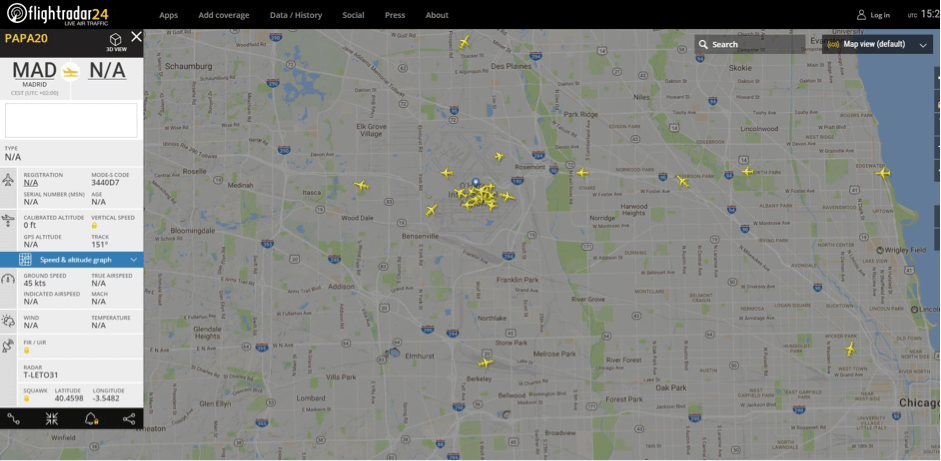

Applications such as Flightradar24 allow us to see air traffic in real time. At an airport, there may be dozens of planes undertaking take-off and landing operations, and all of them must be coordinated by air traffic controllers.

An airport such as Ibiza can have as many as 400 operations per day; Palma de Mallorca airport can have up to 900 at peak times, so the take-off and landing frequency will be one plane every few minutes. And a controller must talk to all of them and give precise instructions as to how to carry out all these operations.

Phraseology, practically a language in its own right

An important part of training for controllers and pilots is learning the necessary techniques and skills to optimise communications between control tower and pilots. These techniques, skills and aviation-specific vocabulary are generally called “phraseology”.

According to the Best Practice Guide: Phraseology and Communications, “amongst the many factors at play in this communications process, phraseology is possibly the most important, as it allows communications to be quick and effective, minimising the possibility of misunderstandings despite possible language differences. Standard phraseology not only reduces the risk of a message being wrongly understood, but it also helps to quickly detect mistakes in a readback/hearback stage. Indeed, the use of ambiguous or non-standard phraseology is one of the most frequent causes and contributing factors of accidents and incidents.”

The information shared during communications must be strictly necessary for ensuring that the aircraft travel in a smooth and orderly manner from the airport of origin to the airport of destination, and to resolve any incidents which may emerge during flight. And that’s where standard phraseology comes in. Non-standard phraseology is used in situations not contemplated in standard action protocols.

Or so the theory goes. In everyday situations, some less than ideal incidents may arise. For example, according to phraseology manuals, the term ‘squawk’ refers to the activation of a specific mode/code/function in an aircraft’s transponder. A transponder is a device which, when programmed, emits a certain code when requested. A sort of “label”.

There are different modes/codes/functions which can be activated on the transponder, such as altitude. And there is a special code for hijack situations: 7500.

One case which actually happened was that of an air traffic controller assigning a squawk code to a pilot. He then asked for altitude and pilot responded 7,500 feet. The controller asked the pilot to squawk his altitude, upon which the pilot replied “Squawking 7500”. By confirming height as a code, the hijack protocol was activated, which meant that the plane landed in an isolated area and was surrounded by three police cars.

The AIM (Aeronautical Information Manual) states that code 7500 must be refused by a pilot unless a hijack situation is really happening. So in this case, it was the pilot who made a mistake. But it is obvious there is a rather fine line in relations between ATC (Air Traffic Control) and pilots.

Maximum accuracy in language

Occasionally, airport operations require special measures to be taken to speed up traffic. For example, pilots can be requested to carry out Land and Hold Short Operations (LASHO), where aeroplanes are permitted to land even if the runway isn’t totally clear, as long as the pilot awaits instructions before crossing a runway taken up by another plane.

This saves time and fuel – two valuable resources in air traffic control – as planes are in the air for a shorter period of time. However, if communications between tower and pilot are less than perfect, very dangerous situations can arise. Including the pilot crossing the runway instead of waiting for the tower to confirm he can do so.

Very often, operations on the runway mean that pilots put their blind trust in controllers. If the Hold Short order isn’t adequately given, the pilot could enter the runway, causing a serious and potentially dangerous conflict.

In such cases, there is usually an accumulation of errors in tower-pilot communications, such as the pilot not confirming the instructions received in an operation with additional risks, or the pilot not carrying out a visual inspection before crossing.

Aerodromes for pilot training

In the case of Cuatro Vientos, situations outside standard phraseology are more diverse and unpredictable. “All pilots have to do a first solo flight at some point, and all sorts of situations arise”, says Alberto Varela, Director of Control Tower at Cuatro Vientos. For example, it isn’t unheard of for a pilot to take off and, simply, get disoriented. Or, even land at the wrong aerodrome.

People like Harrison Ford, who has a pilot’s license, can also make this sort of mistakes, according to Alberto Varela, who mentioned it as an example of this type of irregular circumstance. Recently, Ford nearly caused a serious accident when he attempted to land on the wrong runway at John Wayne Airport in Orange County, California, where a passenger plane with 110 people on board was taxiing.

This incident, as is the case with all irregularities in procedures, is investigated by the corresponding bodies, in this case the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration).

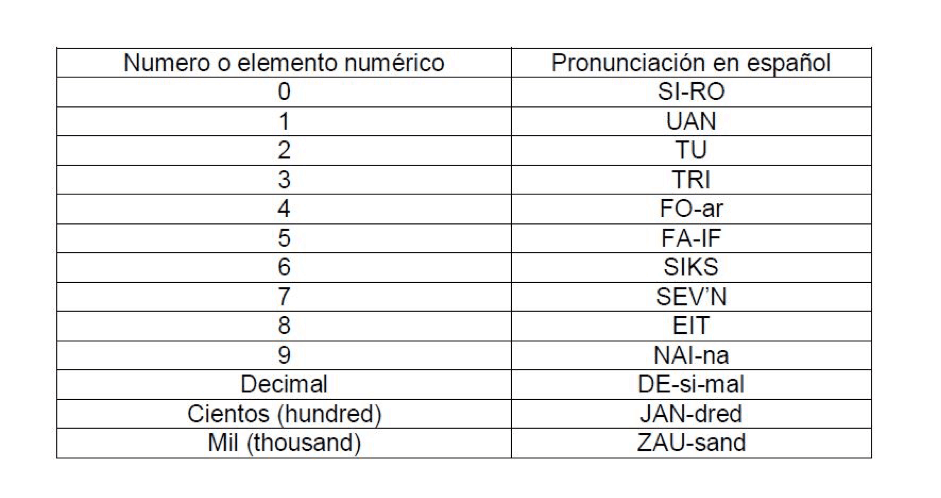

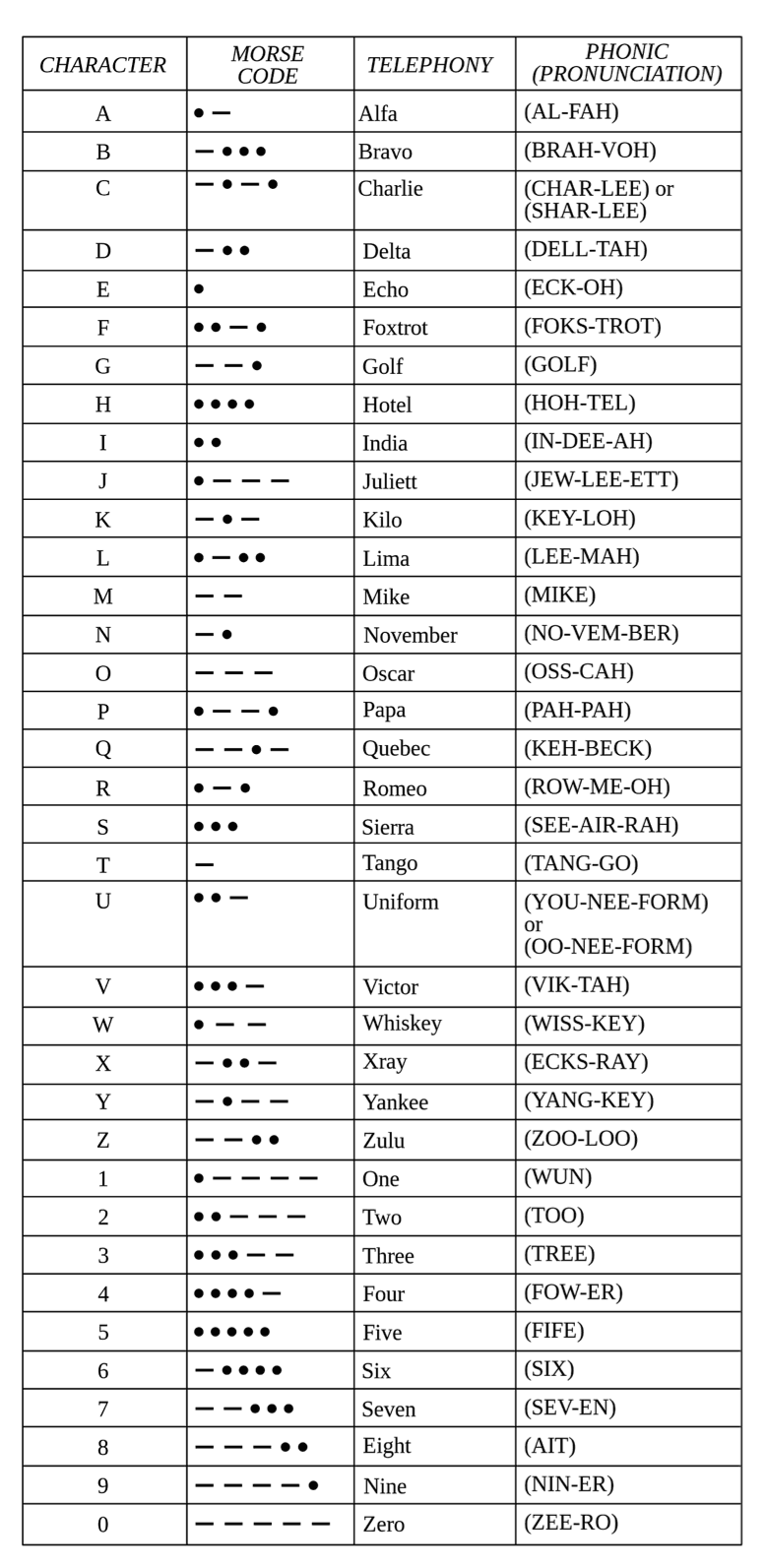

At Cuatro Vientos, the language for tower-pilot communications is Spanish. The rules allow using the local language if there is no conflict with foreign pilots. But the universal language for communications is English. And phonetic indications are even provided to those whose mother tongue isn’t English for pronouncing numbers in English.

The language used for communications in the case of conflict with a country’s local language is English. To ensure there aren’t any problems in pronunciation, phonetic tips are given to standardise pronunciation.

More than just words

Air traffic control phraseology is more than just words. It also contemplates the use of rigid syntax in which perfectly specified elements must be present, in a certain order and a standardised structure.

Whether for identifying the aircraft being controlled, or for meteorological parameters such as wind intensity and direction, confirming orders and repeating requests to verify they have been correctly heard and understood are common practice in tower-pilot communications.

Other rules apply to this phraseology. For example, numbers are given digit by digit. To give a time, only minutes are required. The reason is the use of UTC (Universal Time Conversion) in all aeroplanes and airports throughout the world.

Repetition of certain commands is crucial for avoiding confusion in communications. In some cases, they are a matter of protocol, in others, they are done on request. In this case, the term used is Read Back. To confirm that a message has been understood, the term Wilco (from Will Comply) is used.

Identification of control stations, for example, is done using the place name followed by a suffix indicating the supplied service or type of dependency.

But let’s take an example from one of the many online resources available on aeronautical phraseology. In this case, Tobalaba is an aerodrome in Chile.

Aeroplane: TOBALABA TOWER, (HERE) KILO SIERRA ALFA

Tower: KILO SIERRA ALFA, (HERE) TOBALABA TOWER, GO AHEAD

Aeroplane: KILO SIERRA ALFA, VERTICAL FLORIDA, THREE THOUSAND FIVE HUNDRED FEET, INSTRUCTIONS TO ENTER YOUR TRANSIT

Tower: KILO SIERRA ALFA ROGER, CLEARED TO ENTER LEFT TRANSIT CIRCUIT TO RUNWAY ONE NINE, FIVE KNOT WINDS FROM TWO ONE ZERO DEGREES, ALTIMETRE THREE ZERO DECIMAL ONE TWO, REPORT EN ROUTE WITH THE WIND

Aeroplane: KILO SIERRA ALFA, ROGER

As can be seen, the structure of communications is characteristic and uses words which may seem arbitrary but obey rigid and unambiguous rules, with concrete terms that have very precise meanings.

The table on phraseology terms shows that this is accurate. The phonetic alphabet is used for spelling out letters (as shown in the following image), and numbers are given digit by digit, or with thousands first, then the hundreds and then the units, depending on what information is being given.

It isn’t an exact science

However, this is not an exact science, and occasionally irregular situations do arise. Luckily, they aren’t always a security threat and can even be quite funny.

Generally, it is the pilots who break away from the formalities of the controllers on the ground, though according to the regulations they should stick to standard phraseology.

Sometimes amusing situations arise, such as this language-related one:

Lufthansa (in German): ‘Ground control, what’s our departure time?’

Ground control (in English): ‘If you want an answer, you must speak in English’.

Lufthansa (in English): ‘I’m German, flying a German plane, in Germany. Why must

I speak in English?’

Pilot from another plane (with a British accent): ‘Because you lost the lousy

war!’

(Source: Upsocl)

In practice, a controller’s mission is to reduce aviation accident statistics to a minimum. Statistics which are currently highly “biased” towards security, and a “light-hearted” conversation probably won’t significantly increase the likelihood of an accident. But the fact is that anything that deviates from the norm potentially contributes to the statistics becoming less favourable.

Any ambiguity in communications could result in a controller giving an incorrect order or a pilot taking the wrong action. That’s where the need for rigidity in phraseology comes in.

Each and every irregular event is checked and audited, and, if necessary, rules or recommendations can be changed.

Film phraseology

Now that we know a little bit more about phraseology, let’s take a look at the way it’s been used in some films to work out whether a film is well made or not.

One of the pioneers in this chapter is ‘Airport’, the first film in a saga which lasted several years and which put some of the most famous aeroplanes of the time in difficulty (from 747s to Concorde). The opening dialogue of ‘Airport’ (1970) is one of the most accurate ones on film:

– Global 45, Lincoln Tower. Clear to land.

-Runway two-niner. Wind: 15, gusting 25.

-Roger. Cleared to land. Runway in sight.

-Lincoln Tower from Global 45.

-We cut the taxiway short. We’re stuck in the snow.

-Please notify company dispatch. We’ll need assistance.

-We’ve got a condition four on two-niner at taxiway Echo.

-Change traffic to runway 22. Two-niner’s closed.

-Trans World 729, a change. Taxi to runway 22.

-Runway two-niner is closed.

-Air Canada ninety-niner, hold short of taxiway Bravo. Emergency equipment will pass to your left.

-Runway two-niner closed account of disabled aircraft.

-Approach. Runway two-niner is closed.

-We’ll stay with 22 with everything.

-Global 10, clear for take-off.

….

Other films with more or less standard and dramatised phraseology are Ground Control (1998); “Pushing Tin” (1998), which is a film about air traffic controllers, although reviews by professionals haven’t rated faithfulness very highly.

“Sully” (2016), by Clint Eastwood, is one of the most recent films, telling the story of the water landing by pilot Chesley Sullenberger on the Hudson River after both engines failed just after take-off.

“Top Gun” (1986) is another classic film about planes. It isn’t an especially educational film, but the tower flybys are memorable.

In some films, for example, not even the numbers are given digit by digit, which doesn’t say much for the technical advisors who help screenwriters make the more technical parts credible.

In “Blue Thunder” (1983), an actual controller was taken on to help the screenwriters. And this is an extract of the original script:

“Tower, we have 330 degrees and 15.

Altimeter still 3000.

Clear to land?

1012 traffic, 1:00

two miles north-eastbound.

It’s a Cessna 182 to 5000 VFR.

Blue Thunder down at 2130.”

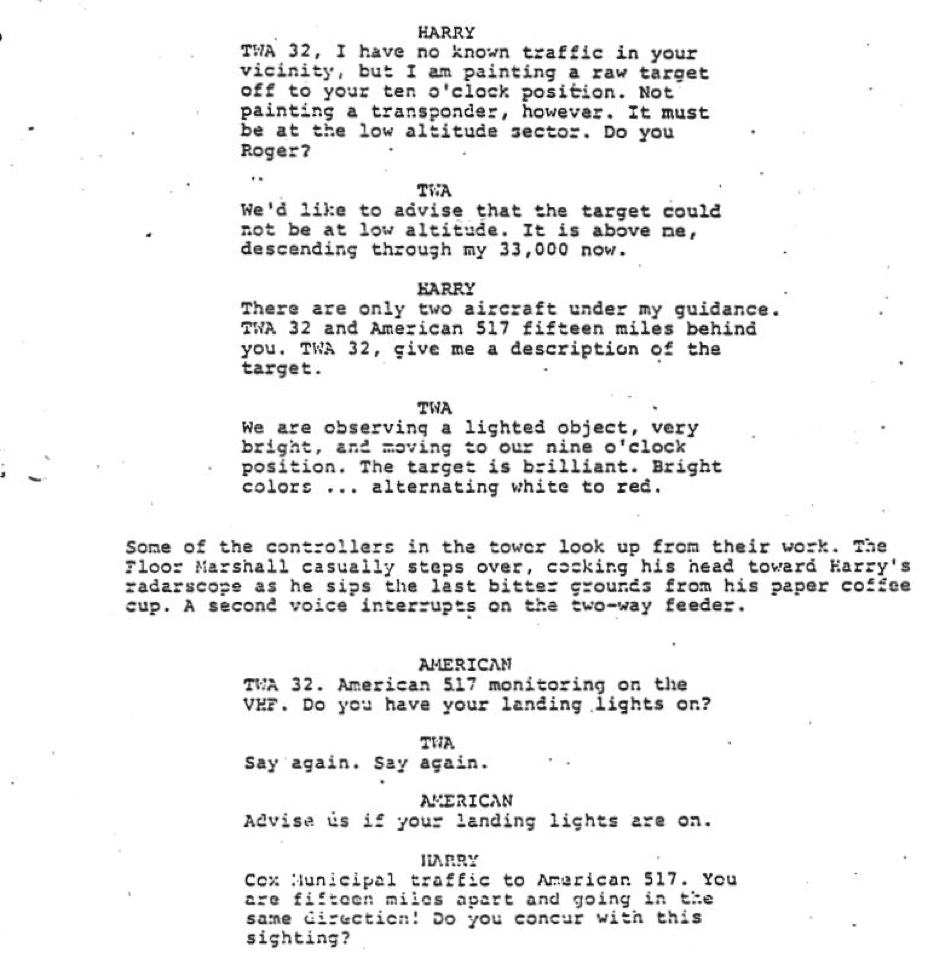

“Close Encounters of the Third Kind” (1977) also features a conversation rated as realistic by those with a certain knowledge of air traffic control.

Image from the original script of “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” showing a conversation between a control tower and a pilot.

Phraseology in real life

It’s well worth listening to live radio stations which transmit real time conversations from the control towers of certain airports.

Web pages such as Live ATC provide access to many different real-time broadcasts of tower-plane conversations.

To collate broadcasts with air traffic in real time, you can simultaneously check FlightRadar24, which will give you a view of a large part of the world’s air traffic.

TABLE

Phraseology terms and their meaning:

ACKNOWLEDGE

Let me know if you have received and understood this message

AFFIRMATIVE

Yes, that’s right or permission granted

DISREGARD

Ignore

APPROVED

Permission granted for proposed action

CLEARED

Permission to proceed under conditions specified

CANCEL

Annul the previously transmitted clearance

READ BACK

Repeat all, or the specified part, of this message back to me exactly as received

HOW DO YOU READ

What is the readability of my transmission

CONFIRM

I request verification of: (clearance, instruction, action, information)

Used alone, repeat, I didn’t understand you, I didn’t hear you

CHECK

Examine a system or procedure

(It mustn’t be used in any other context) (An answer isn’t usually waited for)

CONTACT

Change frequency or establish communications with…

CORRECT

True or accurate. That’s right

CORRECTION

An error has been made in this transmission (or message indicated). The correct version is…

SPELL

Spell portion indicated phonetically

WORDS TWICE

As a request: Communication is difficult, please send every word or group of words twice

As information: As communication is difficult, each word or group of words in this message will be sent twice

MONITOR

Listen out on… (frequency)

Tune in frequency and await call…

STANDBY

Wait and I will call you

SPEAK SLOWER

Reduce your rate of speech

IMMEDIATELY

Must only be used when immediate measures are required for security reasons.

UNABLE

I cannot comply with your request, instruction or clearance (normally followed by a reason)

MAINTAIN

Continue in accordance with the condition(s) specified or in its literal sense, Maintain VFR

NEGATIVE

No or permission not granted or that is incorrect or not capable

REPORT

Pass me the following information…

RECLEARED

A change has been made to your last clearance and this new clearance supersedes your previous clearance or part thereof

GO AHEAD

Proceed with your message or I hear you, you may continue with your broadcast or request

ROGER

I have received all of your last transmission

SAY AGAIN

Repeat all, or the following part, of your last transmission

I REPEAT

I repeat for clarity or emphasis

REQUEST

I would like to know… or I would like to obtain…

VERIFY

Verify and confirm entire message with the originator…

Table

Trade languages. Not only controllers speak “funny”.

Controllers have their own language, but they aren’t the first. Traditionally, language has been used for communicating amongst ourselves, but also for excluding those who aren’t welcome in a group or who aren’t part of that group.

It’s the case of ‘languages’ such as Bron, a dialect or jargon spoken by welders and cauldron-makers (or “xagós”) in Miranda de Avilés (Asturias), former craftsmen and exporters of copper boilers who, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, lost their status as craftsmen.

There are more examples, such as the Latin spoken by stonemasons in Galicia, the “Barallete” spoken by sharpeners in Ourense, or the “Burón” used by traditional muleteers and travelling salesmen from the region of Fornela in El Bierzo (León).

The difference is that jargon here was generally used to talk without the “bosses” getting to know of the various union plots being crafted, while the controllers’ phraseology is designed to maximise efficiency in communications.

There are no comments yet