The first electric street lights in Portugal

Pina Manique, chief superintendent of police and founder of Casa Pia, carried out a small experiment with street lighting in Portugal between 1780 and 1790, when he required shopkeepers to provide and pay for their own street lamps. This gave rise to a very limited public street lighting system using gas, petrol and oil lamps, with a person responsible for lighting them when night fell and putting them out at daybreak.

Terreiro do Paço, highlighting the equestrian statue of D. José I and the lighter of lamps, Municipal Archive of Lisbon, AFML – A12592

Night watchmen (locally called serenos) were very common in the past. Before the advent of electric street lights, public lighting worked because night watchmen used long sticks to light the lamp burners and put them out.

Electric street lighting in Lisbon first appeared in October 1878, when King Louis I of Portugal offered the City Council six Jablochkoff arc lamps which had been used for the first time on 28 September of that same year in the citadel of Cascais, for the birthday celebrations of Prince Charles.

These lights were the same as those used in the square outside the Opera in Paris. The king gave orders to buy six lamps for trialling in Portugal. Up until them, both public and private lighting in Portugal used gas supplied by the Companhia de Gaz Lisbonense.

After the first trials, however, electric lamps were not installed throughout the city given the costs and resources involved, an expenditure which the autarchy at the time was not prepared to make. Moreover, relations between the Chamber and the Lisbon Gas Company were tight to say the least, with a gas supply agreement in force until 1880.

This resistance to the introduction of electric lighting lasted until 1887, with the gas company arguing that caution was called for and this new energy should first be closely monitored; that the cost of buying the new machinery was very high and the concessionary system required to be made with the Chamber very complicated, as the gas network had recently been extended in urban centres such as Belém and Olivais.

Given the difficulties encountered with the Lisbonense gas company, in October 1887 the City Council signed a 30-year agreement with the Belgian company S.A. d’Eclairage du Centre for supplying gas to the city, on condition that they provide electric street lighting in the Avenida da Liberdade and in the Restauradores square for the same price as the rest of the gas lighting. In that same year, the company – which changed its name S.A. Gaz de Lisboa – built a gas plant in Belém, extended the piping network, and installed thousands of gas lamps in the city, thus triggering a large growth in the field of street lighting and paving the way for the introduction of electricity.

And so there was light… electric light.

In May 1889, electric lighting was finally installed in some key areas of Lisbon, drawing large numbers of people attracted by novelty and progress, and sparking comparisons with the modern city of Paris. It marked the end of street lamps as they had been known on the streets of Lisbon.

On 10 June 1891, the old Lisbonense gas company merged with S.A. Gaz de Lisboa to create CRGE, Companhias Reunidas Gaz e Electricidade, which over the next 75 years gradually developed, expanded and distributed electricity in Lisbon, both for private and public lighting. In fact, the last gas lamp was “put out” in 1965.

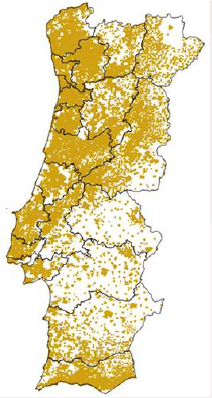

And so began the process of electrifying the whole country, a process which would not be completed until 25 April 1974, when electricity finally reached all of the country’s rural areas.

A more energy-efficient public lighting system

Public lighting in Portugal is largely the responsibility of town councils, who have opted to include public lighting within the power distribution concession. In the event of changes to the public lighting network, these must be approved by the concessionary, and there is a standard system created by the concessionary company itself for the authorisation of agents, both installers and equipment manufacturers. This has the advantage of guaranteeing the quality of such agents, but it is otherwise a very restrictive system in terms of options, and very much in the interests of the actual concessionary company.

Today, concessions for electricity distribution are provided to a single operator, EDP (Portuguese Electricity) Distribuição, which is the holder of the concession for exploitation of the National Distribution Network (RND stands in Spanish for Red Nacional de Distribución) for medium-voltage (MT stands in Spanish for Media Tensión) and high voltage (AT stands in Spanish for Alta Tensión) electricity, as well as local concessions for distribution of low voltage (BT stands in Spanish for Baja Tensión) electricity at municipality level.

The first concessions began in the 1980s, with further public tenders envisaged for 2019 for new concessions. It is expected that from 2019 there will be openings for other operators, as defined in article DL 31/2017 of 31 May, which approves the principles and general regulations relating to the organisation of tendering procedures for the grant, by means of a contract, of concessions for exclusive exploitation of local municipal low voltage electricity distribution networks.

The fact that there is a market which is a virtual monopoly for a single operator has contributed to a very obsolete street lighting network in Portugal. History, however, has shown us that evolution can be delayed but not stopped, and Ferrovial Serviços is an example of this, having installed street lighting for the Vouzela town council. We have been in charge of the management of the public street lighting energy efficiency contract in this municipality since XXXX, and have changed the whole network to LED lights, given that of the close to 7,000 light points making up the system, some 4,000 were at the time still mercury vapour lamps. Mercury is a highly harmful element, both for the environment and for public health. In fact, it is a technology the use of which has been discouraged for many years now, and which is actually banned in the EU since 2015.

Institutional video of the Vouzela town council to present the new LED lighting:

According to figures from the current concessionary company for energy distribution, there are currently close to 3 million light points in 278 municipalities on mainland Portugal comprising:

- 400,000 mercury vapour lamps

- 2.4 million sodium vapour lamps

Despite the fact that current concessions have planned investments for updating the grid which go back to the 1980s (the 20th century), some 17% of light points in the network are still mercury vapour lamps, and LED technology used is as yet so small as not to be even mentioned.

LED technology beyond light: the path to smart cities

With the introduction of LEDs (light-emitting diodes), it is expected that the old technology based on sodium and mercury vapour will be totally replaced over the coming years.

LED technology has revolutionised the way we see public lighting. On the one hand, it is a technology which represents a quality leap forward in the type of light emitted, with much higher colour restitution indexes than sodium vapour, thus completely transforming urban nightlife: where before everything was a yellow/orange colour, we can now see people, buildings and objects in their own natural colour. In addition to this, it also represents significant savings in terms of energy consumption. Savings which can be as high as 60% or 70% if all lighting were simply changed to LEDs, and even greater if flow control elements are added, in order to use the light resources more efficiently. In other words, adapting the light emitted by LEDs according to needs, whether of pedestrians or vehicles.

Remotely controlled street lighting is also a reality in several world cities, allowing the lighting network to be managed through any internet access point.

Today, we can collect real-time information on how much energy each particular lamp is consuming, whether it is on or off, not functioning and why, control on/off switching and light flow, operating hours, etc. This implies a huge decrease in operational costs, avoiding the need to physically send out a team to figure out what the problem is. In other words, an additional saving to that achieved by the actual reduction in energy consumption.

This involves an integral transformation, not only because of this new technology but because of the opening up of the market. This transformation will necessarily affect street lighting, to the benefit of all citizens, since most of us have a lamp close to our front door, school, place of work, etc.

We live in a time of great technological achievements, where the speed at which information is transmitted is crucial and the IOT (Internet of Things) is already a reality, allowing us to transform any object or Thing into a point of access to the Internet and thus a source of information.

Everything conspires for us to stop seeing street lighting simply as a public, often undermaintained, service involving significant financial expenditure for town councils, to become one of our most valuable resources. Town councils will be able to contract the same street lighting network out to different companies for different uses: lighting, information, communications…, with the need that first gave rise to it – the lighting of streets and roads – being conceivably but a small part of its future role.

The public lighting network will become a means for transmitting information, accessible to all, thus enhancing democratisation of access to information.

It’s not difficult to imagine each street lamp as a point of access to the Internet, with specific information on the municipality, the area, important references or contact numbers, etc. For example, a number of street lamps in a certain area could carry relevant information on the area, such as public transport schedules, restaurants, bars and other services. All of these possibilities are there and would lead to smart cities, with street lights evolving beyond being a mere collection of installations and services.

This evolution in thinking will allow greater returns on investment for communications infrastructure and the introduction of additional uses, such as:

- Waste management

- Environmental monitoring (air quality, noise maps, etc.)

- Monitoring of forest areas

- Irrigation management

- Monitoring of public infrastructures and buildings (security, environment and technical management, amongst others)

- Parking management

- Rental bike infrastructure management

- Traffic management and sensors

- Agriculture and livestock management

- Public lighting

In other words, it will transform our current urban centres into smart cities through the use of sensors (for movement, parking, noise, environment, etc.) with open communications protocols, allowing interaction with other platforms used for collecting information on the city. Technological developments allow us to think already of real solutions with a practical application in the short term such as, for example, the use of the LoRaWAN network, which has the following characteristics:

- Long range: 3 to 15 km

- Low energy consumption

- Low cost: reduced CAPEX, almost no OPEX

- Reduced broadband: 400 bytes/hour

- Flexible, dynamic cover

- Safe: 128-bit end-to-end encryption

But all of this requires investment and integral thinking, and urban planning viewed from a holistic perspective.

What started out as a very limited public street lighting system using gas, petrol and oil lamps, changing gradually to more modern electric power, and subsequently improving with the change to LED technology, is exactly what happens in the real world. In other words, we find it difficult to change, but progress is a must and technological changes happen ever faster and demand constant renewal. LED lights, practically infinite in their duration, are the first step on the road to a truly smart city.

There are no comments yet