Open an app, press a button and a car comes to pick you up. This was the future Travis Kalanick and Garret Camp envisioned in 2009 when they decided to create Uber. They probably did not imagine that their new company was going to aspire to achieve a $100bn valuation and transform the world mobility paradigm, giving rise to a new industry, that of Transportation Network Companies (TNC).

Source: Time

But, how has this new service affected the airport business, beyond the fact that some passengers now use Uber -or similar services like Lyft– to get to the airport?

It has certainly had a significant impact. The emergence of TNCs has influenced the way in which passengers choose how they travel to the airport more than it initially may have seemed. This phenomenon has challenged a considerable part of airport revenue and, over the last few years, has caught the whole industry’s attention, with several studies and articles on the topic being published, such as that of L. E. K. Consulting Firm.

Source: stuckattheairport

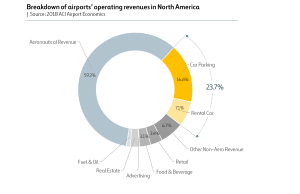

Firstly, it must be explained that the various methods of accessing an airport are as important for transportation reasons – since airports are usually located at a significant distance from the city center – as they are for economic reasons. These modes of airport access contribute decisively to the sustainability of the airport economy, adding up to, on average, around 25% of total operating revenues in North American airports, as it is shown in the “2018 Airport Economics Report”, published by ACI. Therefore, at first glance, it seems that the outbreak of this new form of mobility could have a great impact on airport finances. Given the higher maturity and impact of this service in the U.S., we will focus on understanding what has happened in North American airports.

Adoption of TNCs in the North American market

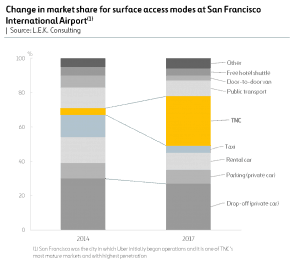

The use of Uber and other TNCs in the US has been massive – in San Francisco, for example, in 2016 the ratio of TNC to taxi journeys was 12:1 as shown in this report published in 2017 by the San Francisco County Transportation Authority.

Initially, one may think that this demand for TNCs has been completely taken from taxis and chauffeur-driven vehicles, given that they are very similar services. However, although it is certainly true that a large part of the demand comes from taxis, it has also, less dramatically, eaten away at other ways of accessing airports, such as personal vehicles that use parking, rental cars, and even public transport. The explanation for this phenomenon could be derived, according to survey results, from the fact that passengers see TNCs as a different service, particularly valuing aspects such as service convenience, competitive price, and the ease of use.

Another interesting change that it has caused in passenger behavior when choosing a mode of transport to use to get to and from the airport, is that some users, who used to travel in a personal vehicle driven by a friend or family member, now use Uber or another TNC. This seems to show the passenger sensitivity to price, since the cost of TNC services have decreased to the threshold at which a passenger may prefer this alternative rather than having to resort to favors from friends or family.

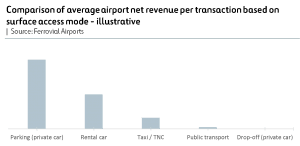

But, how does this new mobility system affect airport revenue? If we consider the average value per transaction for each airport surface access mode, we find significant differences. Modes of transport such as private vehicles parked in the cark park or rental cars generate high yields per transaction, whilst taxis, TNCs, or public transport generate lower yields.

Therefore, the increase in the use of TNCs means a significant loss in high-yield transactions, which could harm airport revenue. So, how is it possible to generate similar revenue in this new scenario?

The answer lies in the transactions that TNCs have gained from the passengers who previously accessed the airport via private vehicles driven by friends or family. This type of transaction doesn’t generate any revenue, since in the US they are not subject to any airport access fee. Therefore, the solution must find a suitable balance between the limited loss of the high-yield transactions and the monetization of a relevant volume of transactions which previously did not generate any value.

Source: hiveminer

Therefore, if airports implement an appropriate pricing and segmentation strategy – which on the one hand distributes demand optimally among the various access modes of transport and spaces in the airport, and on the other hand, generates an appropriate yield from new TNC transactions – in most scenarios, it will manage to maintain passenger revenues at a similar level to that of when before Uber existed.

In any case, the irruption of TNCs is not the only challenge facing airports. Other trends which are quickly developing, such as integrated systems for Mobility as a Service (MaaS), self-driving vehicles, and Hyperloop, will require the airport industry to adapt, sooner than it may seem, its business model in order to continue offering a competitive service in the future.

Source: Detroit Driven

To overcome this reality, the most effective strategy is anticipation and agility, which allow us to proactively manage change; because, from the right position, what may seem like worrying threats could become interesting opportunities.

There are no comments yet