Drones have become a common sight nowadays, but their beginnings date back to the 1940s, when the construction of a UCAV (Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicle) called Killerbee was proposed as part of a military combat project. Attention then shifted to surveillance and observation and, as a somewhat ironic play on words, these aerial vehicles came to be called drones.

Since then, UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles) have been used mostly in the military sector, on observation and combat missions. In general, these drones are worth tens of millions of dollars, have a range of hundreds of kilometres, and the capacity to transport radars or bombs.

But for some time now, drones have also emerged in the civilian world, not just as toys but also as devices that can fly at heights of more than 100 metres with a range of several kilometres. Some of these are of significant size and weight, and have very useful professional applications.

Indeed, Ferrovial in 2015 already secured a licence to fly drones in Spain for operations such as inspecting infrastructure and public lighting, and buildings management. A field of work which is constantly evolving and where there is still a lot to do, but which is already proving to be extremely useful for improving infrastructure management.

Drones and airports

But however much fun and however productive drones may be, they are devices that fly in airspace. An airspace in which there are also elements such as electricity cables, structures such as buildings or bridges, and others. And which must be shared with birds and, of course, airplanes and helicopters.

It may seem that airplanes fly at very high altitudes. Or that a drone is like a mosquito next to a plane and therefore, if they were to collide, nothing would happen to the plane. But this is not the case.

A drone weighing between 1 kg and 3 kg in collision with a passenger plane during take-off or landing at speeds which may range from 180 to 350 km/h, or with a helicopter or light aircraft, can seriously damage the structure of the plane or some of its flight systems, including the engines.

Airspace, which to us may seem immense and uniform, is highly regulated in order to avoid conflicts in use. With a growing number of aircraft in the air, and the proliferation of helicopters and, now, of drones, it is important to know where flying is allowed at any given time.

AESA, the Spanish Aviation Safety and Security Agency, is responsible for ensuring appropriate planning and use of airspace. For instance, the 120-metre height limitation for drones flying under any circumstances is due to the division of airspace into different altitude bands. You can check current legislation here.

Controlled and limited airspace

Basically, there are two types of airspace: controlled airspace and limited airspace. Controlled airspace is the area around airports, where safety protocols which controllers have to follow in the event of an incident apply.

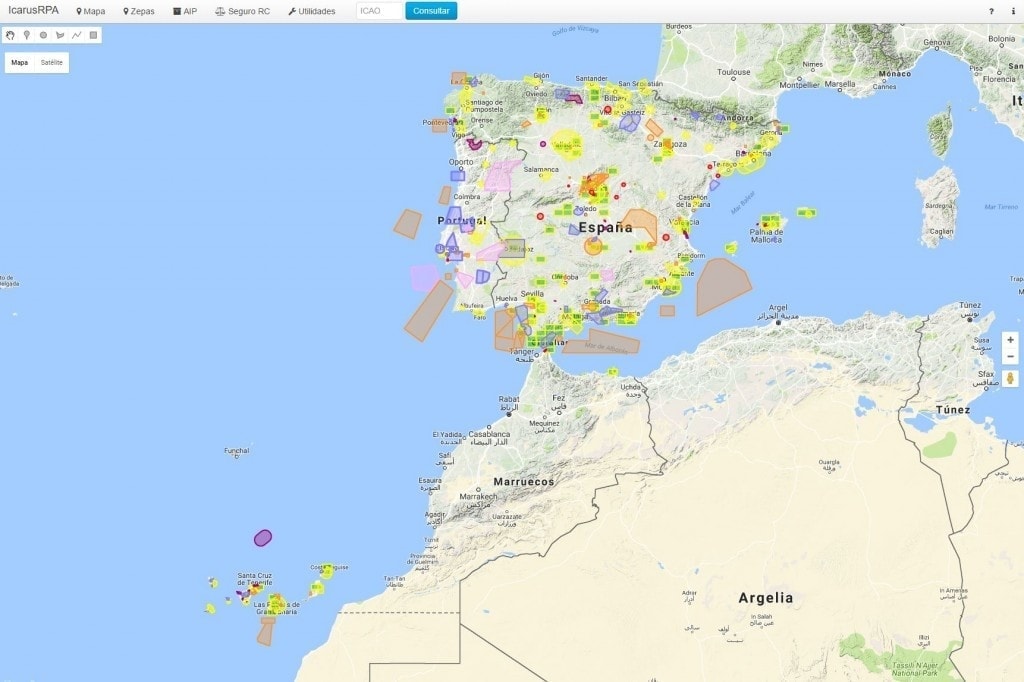

For a general view of Spain’s airspace zones check out this interactive map. In general terms, controlled airspace covers areas of between 8 to 15 km around airports, depending on whether visual or instrument flight procedures are used.

It is possible that outside these areas there may be other bans in place due to being in a limited airspace, but what is absolutely certain is that drones cannot be flown near airports, at least within the 8 km radius.

During our visit to the Cuatro Vientos Control Tower we were lucky enough to talk to Alberto Varela, Control Tower Manager, about drones and how they affect a controller’s job. Cuatro Vientos uses visual flight procedures, so the radius of controlled airspace is 8 km.

Despite the above, Alberto told us that they were just reporting a recent incident with a drone to AESA. In controller jargon, when a drone is detected in controlled airspace it is called a ‘sighting’. And far from being anecdotal, they constitute serious drawbacks with many negative implications for air safety.

Some important crises

Incidents with drones aren’t something new, but they have experienced a surge in recent years with the increase in popularity of very powerful drones at affordable prices. All accidents are equally important in terms of personal and material consequences, but those involving large, commercial passenger planes such as the Airbus A380 have potentially greater impact.

According to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), 764 incidents in which a drone put a passenger plane in danger were reported in 2015.

In March 2016, an A380 with more than 500 passengers on board nearly collided with a drone at an altitude of 1 500 m on its approach to Los Angeles. In February 2016, an A320 also had a near miss with a drone on approaching Paris.

In Spain, an incident with a drone was reported in Santiago de Compostela in December 2015.

None of these cases resulted in a collision, but safety was severely compromised in a field where any deviation from the norm may tip the safety balance and cause an accident.

What is done in the event of a sighting?

Although it may appear simple, the procedure followed by controllers in the event of a sighting is critical for maintaining the safety of control tower operations.

According to Alberto Varela,

The sighting of a drone is considered a safety incident. AESA takes these incidents very seriously and, whenever there is a sighting, they ask us for all types of additional information. It’s a difficult issue. Many of the drones are probably toys. But they still pose a risk.

Regarding regulation, Alberto Varela claims that drafts have been drawn up to integrate drone activity and airports. For the time being, however, what is in place is a ban. Drones fitted with GPS usually have the coordinates of protected airspaces saved in their systems, in such a way that they will not even operate in controlled areas. But these drones can be, and sometimes are, manipulated to avoid these restrictions.

The procedure in the event of a sighting is simple, Alberto explained. The controller alerts the airport, which in turn calls the Guardia Civil (a special police force) for them to take the necessary measures. Once the incident is reported, AESA may ask for further details and, in the general context of tower operations, action protocols may be amended on the basis of an incident.

Legislation is stringent in these cases, and heavy fines are imposed. In this sense, there are precedents such as that of an Al Jazeera journalist who used a drone to take aerial videos of Paris and received a 1 000 Euro fine for not having the relevant permission. In Spain, the fines for breaching the law range from 4 500 Euros to 7 000 Euros.

In many cases, these violations may occur due to lack of information or awareness. Eight or 15 km is a considerable distance, and it is possible that we wouldn’t even know there is an airport or aerodrome close by. An issue with potentially very serious consequences.

There are no comments yet