“The most advanced technology in building construction to date.” That was the opinion expressed in the 1975 World Congress on Architecture and Public Works held in New York on the Torres de Colón in Madrid. Known originally as the Jerez Towers, the Torres de Colón are two skyscrapers located in Madrid’s Plaza de Colón which were built in reverse, from the top down. A case of “starting the house by the roof,” as the saying goes in Spain.

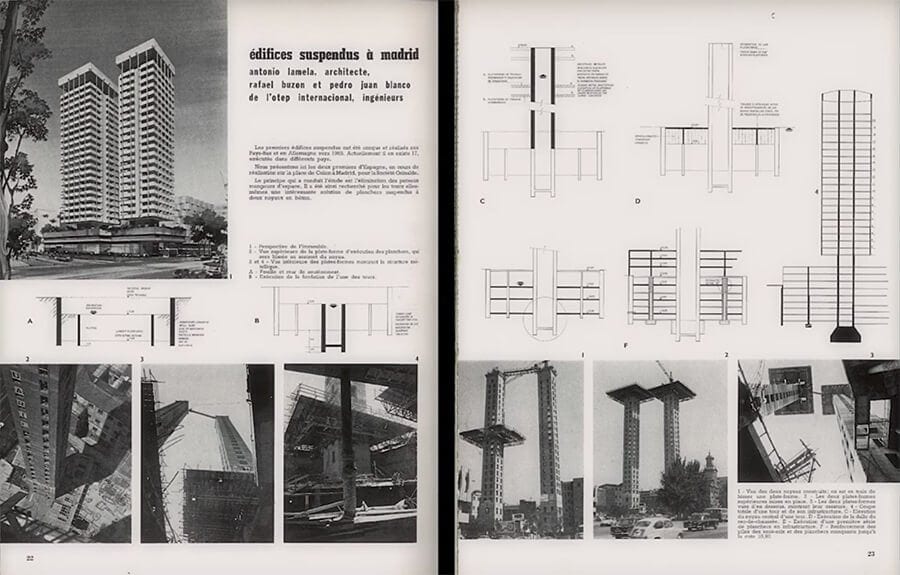

The towers were built between 1967 and 1976 by architect Antonio Lamela (Madrid, 1926-2017). Their suspended or hanging structure was a technical novelty at the time, and the building constitutes one of the architect’s most symbolic works. The documentary Torres Colón: Antonio Lamela’s hanging architecture, by Héctor Gómez Rioja, reviews the history and the repercussions of the work of this Spanish architect, who died on April 6 of this year.

In addition to the documentary in memory of the architect, the professional association of architects of Madrid published the book “Antonio Lamela y Torres Colón: Historia de una de las realizaciones más relevantes de la Arquitectura y de la Ingeniería estructural del siglo XX” (Antonio Lamela and Torres Colón: The story of one of the most impressive works of architectural and structural engineering of the 20th century), in which Concha Esteban charts the life and work of the architect, from his first commissions to his most iconic works both in Spain and abroad.

How the Torres de Colón were built

The video (Starting from the roof) visually explains the process of construction of these two towers, which began with the provision of a core pillar from which the tower floors would hang. At this stage of the building process “people still had absolutely no idea of what these towers were about. ‘Who could be crazy enough to build such narrow buildings?’ they wondered.” The hanging structure model was new at the time, having been applied in fewer than 20 buildings in the whole world.

However, following construction of the Torres de Colón, “Spanish architecture adopted and developed the hanging model”, according to the publication Informes de la construcción (Building reports) in 1977. The publication also explained some of the reasons why Antonio Lamela opted for this type of structure… “the only possible functional solution given the nature of the plot on which they were built – small and irregular – and the character of the projected towers – tall and with a reduced floor area. The hanging structure, supported on the ground by only a central concrete core, allowed the provision of ramps and parking spaces in the basements, something which would have been practically impossible in a traditional building, and meant that there were no structural constraints on the internal design of the tower floors, thus allowing the flexible open-plan distribution required for the proper functioning of the offices they were envisaged to house.”

The documentary describes some of the challenges which the builders faced, such as that relating to the freezing of the concrete. Concrete was prepared in non-stop shifts, 24 hours a day. As the sliding formwork crept upwards, the concrete was carried up by a lift provided within the core. At a certain height of the tower, wind speeds could reach over 100 km/hour “…so the concrete froze as we put it in the core, and when it got to the top there was no way it would set. The concrete had to be heated before sending it up, so that it was still warm when it got there and so could be used,” explains Amador Lamela in the documentary.

The use of concrete created greater challenges than a steel structure would have done, but Lamela preferred it because it meant that the building would be more resistant in the event of fire. In addition to the greater complexity in the use of concrete, the hanging structure drove up the cost of the building by between 10% and 15%: the cost of building the Torres de Colón was 1 700 million pesetas, or over 10 million Euros at the time.

Some years ago Antonio Lamela explained in an interview why it was that he decided to build two towers, instead of one. “We thought of one tower initially, but it would have had to be too tall, with over 40 floors, and it would not have fitted in at all well with the landscape. So I proposed to my clients that we have two towers instead of one, in order not to break up the city skyline. I had a difficult time with this, as the town council architect insisted it was impossible. “You are planning something that goes against the rules, because instead of one unit you bring me two towers.” To which I replied: “Excuse me, but that’s not correct. What I bring you is a couple of towers. A couple is a unit comprised by two individuals.”

Antonio Lamela and Ferrovial

Throughout his career, Antonio Lamela worked with Ferrovial on several projects, such as the extension of Warsaw airport. The construction of Terminal 2 and the north pier “marked a turning point in the history of construction of large works in Poland”, which until then had been very much influenced by the construction styles of the post-communist period.

Lamela also worked with Ferrovial on the construction of Terminal 4 of Madrid-Barajas airport (2000-2005), with its spectacular ceiling, and on the Ebrosa (Property Developer) office building in Sanchinarro (Madrid). The Ebrosa building is unique in that its all-glass façade lights up with different colours at night, and the construction design uses the garden areas around it to regulate temperature and humidity in the building more efficiently.

There are no comments yet