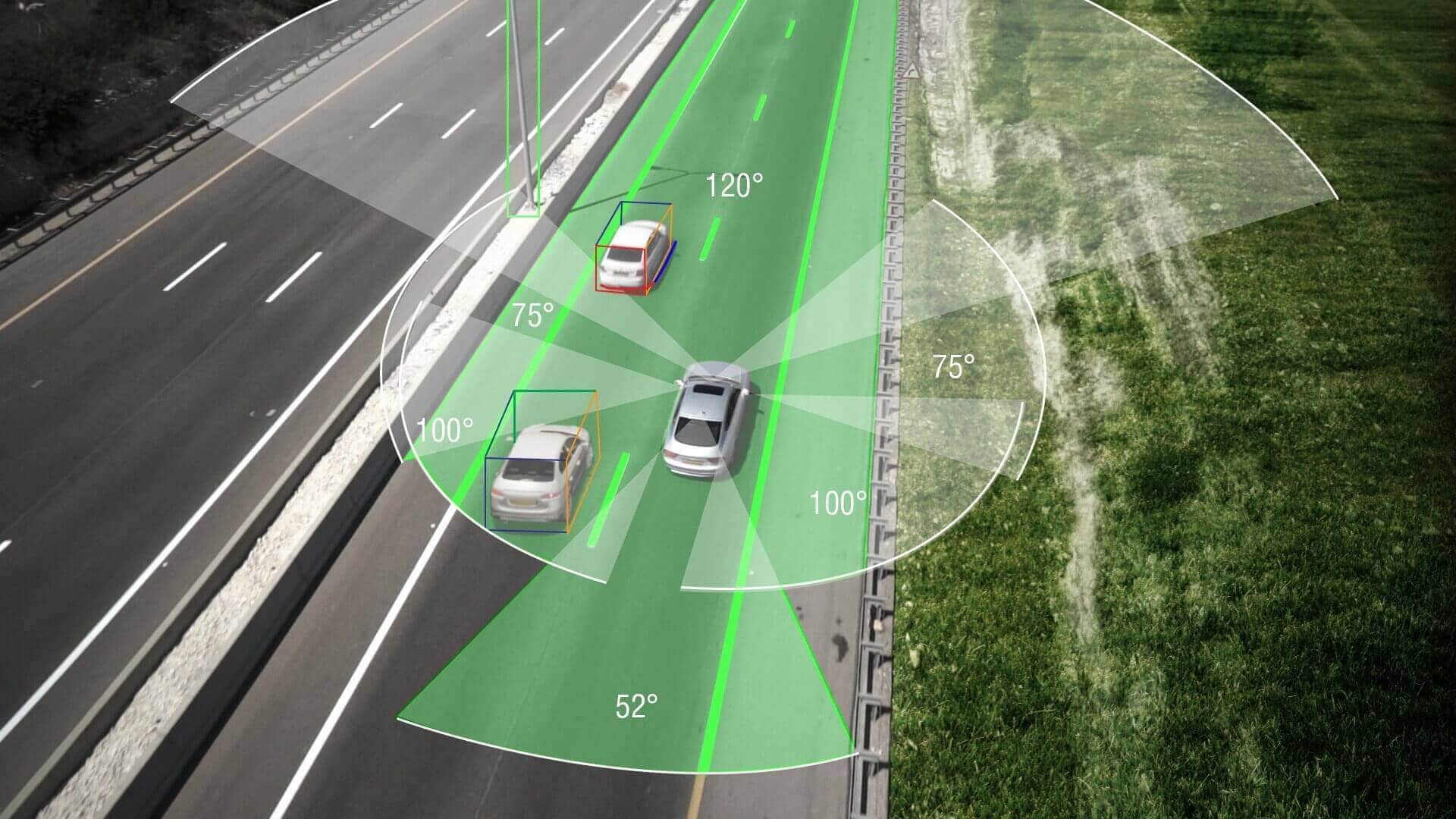

One of the challenges for further development of autonomous vehicles and their adaptation to environments such as cities and motorways is that they must be totally safe to drive. This can be achieved through the considerable number of sensors and cameras they are fitted with, including high resolution video and sensors. But beyond sensors – and these can be many, varied and practical for use in contingencies –, the best technology is having a good map of the motorways, roads or streets that the cars are to drive along.

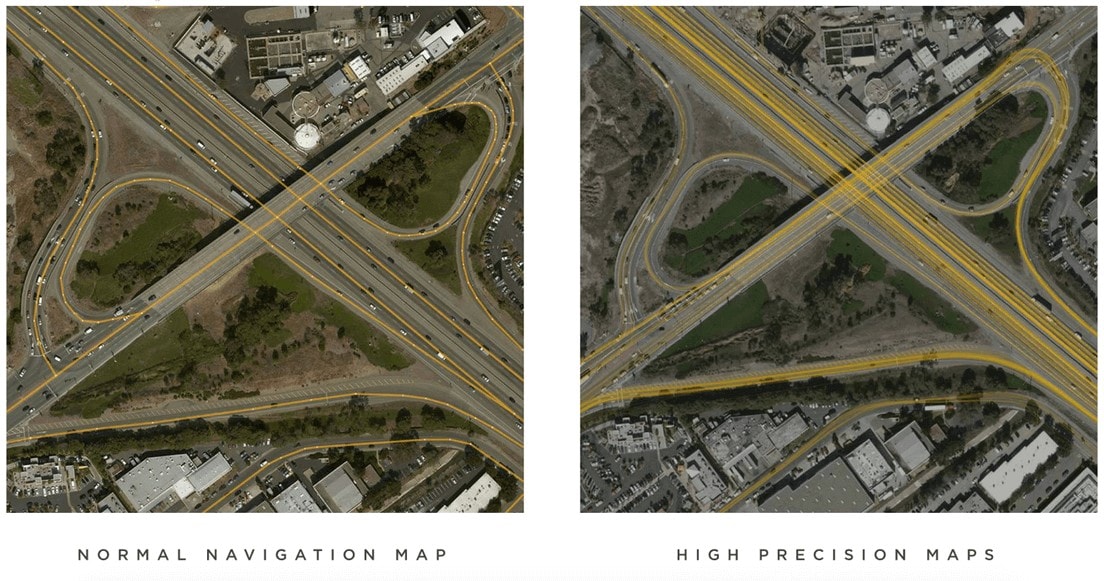

In this sense, it is an enormous advantage that there are ever more and better highly accurate maps, thanks to the huge development of aerial and satellite photograph technology. Maps – and these include not only Google Maps or Nokia Here, but also maps from other specialist suppliers and services (Garmin, Navigon, MapBox) – are highly accurate and useful. But their usefulness relies on knowing the vehicle’s exact position, something which is usually calculated through GPS positioning.

GPS dependency

This causes a series of problems. First of all, GPS cover is not always available (for example, in tunnels or narrow streets with large skyscrapers nearby), and, on the other, even if there is cover, GPS is typically accurate to a few tens of metres only. And despite the fact that there are “improved versions” in certain GPS receivers, with new enhanced positioning, such versions are not yet available.

But there are other technologies. One of these is that used by Tesla, which obtains data from its own fleet of cars to “improve” maps. Amongst other things, such data divides a large motorway into its various lanes, draws wider-angle bends which more clearly resemble those actually taken by cars when driving, and pinpoints more accurately the position of street junctions and motorway access and exit slip roads.

Tesla boasts that its Fleet Learning system makes for more accurate maps, including traffic signs and other markings which do not normally appear on maps. A practical example is when there is a sign on a sloping road or a tunnel. The car cameras or radar would detect this object and could believe that the car was on a collision course (neither the GPS nor the altimeter have the required degree of accuracy to know whether the car will have sufficient clearance or not). But the vehicle fleet will have previously already detected such signage and stored it in the database, together with the fact that cars usually get through without any issues. If in this sort of “improved map” the cars in the fleet have not braked when they supposedly should have done so to avoid the (inexistent) “obstacle”, the conclusion is that it is safe to go through, and therefore emergency braking is not triggered.

New maps for a new era

Other manufacturers such as Mobileye/Intel use a technology called REM (Road Experience Management) with the aim of reducing what is known as the TTRR (“Time to Reflect Reality”) for the car’s “brain”. REM is a kind of ultra-high-resolution map, not only of the roads themselves, but also of the road signs and other road markings.

Data feeding the REM comes from any car equipped with a camera. An analyser studies the position of the car at each point of the video and analyses these images searching for recognisable elements, such as traffic signals, lanes, etc. By uploading information from several cars on a particular location on a single server on the cloud, a more accurate version of the map at each point is created: the definitive ultra-map.

It is not surprising that some Tesla engineers created the company Lvl5, which specialises in creating maps using these technologies from videos provided by drivers, a type of collective initiative (crowdsourcing). Their idea is to subsequently license it for use by different car manufacturers.

Demonstration videos show the REM system working in a driverless vehicle next to an aerial image from Google Earth. Yellow lines show the “physical boundaries”, i.e. the sides of the streets or roads. The purple lines show the lanes and the green lines the ideal path for cars driving in each lane. The aerial image shows the same data superimposed on a conventional map, with circles indicating vertical sign posts (speed limits, bans, etc.), such that the car knows where it can go, where it cannot go, and where it will find complementary information. All this information is used to improve its positioning.

New infrastructures

Projects for adapting and enhancing motorways, such as VIRIATO (Vehicle Road Infrastructure Adaptation test under Open traffic) also aim to help cars with more accurate mapping from the road itself. This project, which has been test piloted in the Norte Litoral motorway in Portugal, managed by Cintra, combines several technologies.

One of these is the differential correction system which can improve the accuracy of GPS positioning systems in autonomous vehicles up to around 1 cm. This is tested in low and high-speed tracks, with two types of vehicles (a connected-type vehicle and a driverless vehicle), as well as on real stretches of motorway, taking care to interfere as little as possible with actual traffic. The technology used for the correct positioning of vehicles is differential GPS – which provides high quality and minimal error, better than mainstream GPS –, which complements preloaded high definition maps, reading of road markings and preloaded maps with a high level of detail. These three sources of data provide a high degree of reliability for the vehicle to drive to high safety standards.

Adaptation of tunnels is one of the most important aspects: this is where driving is always more difficult, given low visibility and little or no GPS cover. Here, visibility is improved to aid the functioning of car sensors reading the road markings (lines and lane separations).

Certain points of road infrastructure require special attention when introducing technology for vehicle autonomy: these are motorway access slip roads (critical points for driverless vehicles, as are exit slip roads) using traffic monitoring systems; more signage or communication between vehicles, and warnings of sudden congestions or incidents. There is also the possibility of adding special infrastructures: one of these is emergency stops where autonomous vehicles can get to on their own if the driver does not react within a given time; or fast lanes for use by autonomous cars only.

All of this is in line with the strategy for development of autonomous vehicles in the coming years, evolving from what is known as Level 1 (no autonomy) to the current state (Level 2 and 3, partial autonomy) and up to Level 5 (the sought-after 100% autonomy). This will perhaps become a reality around 2030, which is when vehicles may have better road and motorway maps, in addition to more accurate and fast sensors for acting in real time.

There are no comments yet