The age of floating transportation and its implications for major cities

17 of October of 2018

The ways that we get around in cities are constantly evolving. Current trends are moving toward renting over owning property, and in variety of ways of covering short and medium distances. Thanks to this, all sorts of “mechanical inventions” beyond cars, motorcycles, and bicycles are cropping up, as well as new formulas for hiring them out. It is an interesting future that presents many challenges for cities.

Those in charge of Citymapper, one of the most popular apps for planning how to get around in big cities, have coined a term for all of these new forms of mobility: the suggestive designation of “floating transportation.” Unlike traditional services, these do not have fixed stops or infrastructure, and they can take the form of any vehicle, always available where people need them.

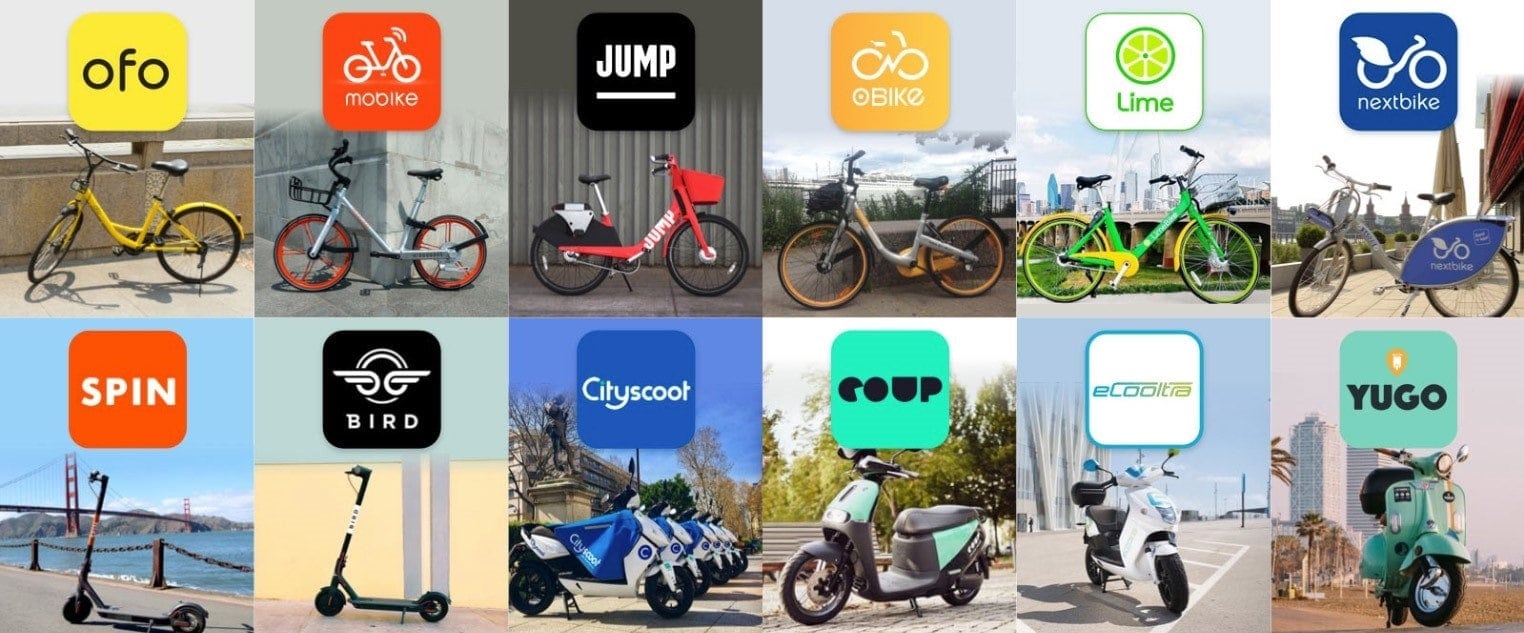

Making a comprehensive list of these new modes of transportation would be almost impossible: apart from private vehicles, there are:

- Fixed-term car rentals (carsharing)

- Bicycles for loan or rent

- Electric motorbikes

- Electric scooters

- Segways

- Hoverboards, unicycles, skates, and the like

Many of these modes of transportation – almost all of which are electric or hybrids –reduce polluting emissions and noise, contributing to the betterment of cities. But it is from their coexistence with cars, buses, the metro, and pedestrians that problems also arise: where do these vehicles operate? Where do they park? It is convenient for them to share the sidewalk with pedestrians?

Curiously, what seemed like an idyllic future has become a headache for those who invent and promote these alternatives, since they did not talk to those who use them: urban regulations, conflicts with already-established sectors (like taxis), vandalism… It looks like the future was more complicated than it seemed.

Mobility linked to phones and apps

Source: Unsplash | Author: Yomex Owo

Floating transportation shares several common characteristics. One of them is that it is almost always linked to mobile phones and the apps to access each service. The phone serves to locate electric cars, motorcycles, or bicycles on the map, as well as unlocking them and starting them. And they are also the most natural payment method, linked to a credit card – though in some cases, like that of BiciMad, special cards or cards combined with the other modes of transportation in the city are needed. Additionally, companies make sure that the people who use these services are perfectly identified, and that they have clear contracts, the proper licenses (like a driver’s license), and insurance in order.

Aside from that, these transportation networks usually provide their information to the companies that develop mobility apps so that users can search Google, Citymapper, and similar apps directly for the various ways to make a trip – without having to open five or ten different apps to search for availabilities on each service when they want to go someplace. In this sense, the trends of smart cities point toward open data, which, in the case of transportation operated by public administrations, is almost universal nowadays.

Regulations that must be settled

Source: Flickr | Author: mhobl

Since there have been people who have walked while others rode horses, there has always been some conflict over the use of public routes. In the 21st Century, this can sometimes come to seem like a “free-for-all” that is hard to resolve: drivers against cyclists on roads; cyclists against pedestrians (in the bike lane) and pedestrians against cyclists (on the sidewalks); tourist vehicles like Segways and tandem bicycles against everyone else… Who does the road belong to, the sidewalk, the bike lane, the parks? It is no joke: there are even pedestrians who feel steamrolled by the ever more numerous runners, and they in turn feel pushed around by regulations like the Ley de Seguridad Ciudadana (Public Safety Law) to the point that the Traffic Department had to confront the issue and clarify that it would not ticket runners for breaking the speed limit while using sidewalk space for sports practice.

The recent invasion of electric scooters and other next-generation vehicles is a perfect example of the implications of this difficult coexistence. To start with, mobility regulations and ordinances vary between cities, and moreover, they change frequently over time depending on “fashion.” Even though these scooters technically qualify as “personal mobility vehicles,” there are several types, and a scooter is not the same as a Segway, a hoverboard, or a unicycle. They are generally differentiated by their maximum velocity, weight, and risk factor (among other things).

Even though some of these vehicles may be operated on roads – depending on the type of street and if it is one way or two, has several lanes, etc. – the “steamrolling effect” that cars and buses have makes those that use these new contraptions tend to use the sidewalk. They then come into conflict with pedestrians, who see how the stealthy scooters that can weigh up to 25 kg “fly by” at 20 km/h right next to them. This is more or less as it has been for a long time with bicycles – which also have conflicts with scooters, skates, Segways, and more in their dedicated lanes. Common sense suggests that, when sharing the sidewalk, the speed limit should be that of a “person’s walking speed,” but not everyone respects this.

So many gadgets, so little sidewalk

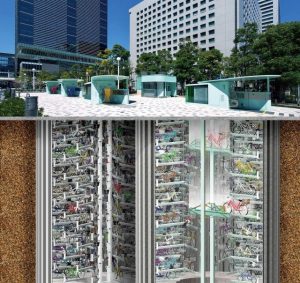

Source: Giken.jp

Another source of friction is parking. Just as there are those who complain about the “invasion of bar terraces” in some cities because they reduce the amount of sidewalk space for walking, there are ever more floating vehicles parked on the sidewalks. In addition to the motorcycles and mopeds that can park on the sidewalk as long as they are not a bother and leave enough room to get by, there are now bicycles that, unlike services like Bicing in Barcelona or BiciMad in Madrid, do not have their own bases and can be left anywhere.

For this problem with the electric bikes and motorbikes, the British newspaper The Telegraph used the dichotomy between “the future of transport” or “street litter.” Various world capitals have faced the same problem: as these bicycles only have a GPS, there are not enough bike racks on the street, and many people do not park them responsibly where they are not in the way. They then wind up abandoned wherever, vandalized or piled up as if they were junk – passing the problem on to the next person who wants to use one. Mountains of bicycles: yellow, red, blue… They are so cheap that they go from being hundreds to thousands in just a few months: they are called the Uber of Chinese bikes. The color changes, but the problem stays the same.

Solutions for all tastes

None of these situations has a simple, definitive, tested solution, but the companies and entities that manage floating transportation have learned from experiences in other cities, and moreover, technology always helps.

In addition to planning cities with better bike lanes that all sorts of users of alternative modes of transportation can use – including electric scooters – many initiatives are looking to expand parking spaces specifically for bicycles. Some are urban parking lots restructured for bicycles, like those of Don Cicleto in Madrid, Barcelona, Zaragoza, and Seville. In Japan, a company called Giken has robotized, subterranean parking lots that lower bikes up to 11 meters below ground to leave the sidewalk free for pedestrians. Ideally, the new bike racks would also be equipped with power outlets or chargers. In some cities, it has even been suggested that one parking space for a car should be changed out so that up to eight bicycles can park in front of every supermarket – to the benefit of nearby businesses, as well as the safety of the bikes themselves and traffic, too.

Those who manage floating transportation have also learned a lot in these years: data collected about where trips start and end allows planning certain actions better, with trucks and operators to carry bikes from the center to the periphery (or vice-versa) depending on the time of day in order to avoid shortages or bases being full. Vandalism has gone down with surveillance cameras and better antitheft systems. As for carsharing, the areas of circulation are growing as time passes, and they may now reach zones like airports close to cities, an important need for those who use cars for work.

A technical way of solving some of these problems includes allowing advance reservations so that it is easier to find a car, motorbike, or bike when needed. Standby fares also play an important role, which, as in the case of Zity electric cars, allow users to keep them at a reduced rate if they are going to make several stops in one trip or if they want to make sure that it will be available for the return trip when parking somewhere for a while.

Every city has its own peculiar characteristics, and some solutions are more adaptable than others. But what seems clear is that floating transportation has come to stay, and urban planning for the cities of the future, and adaptation for current ones, must take it into account.

There are no comments yet