What do a ghost base, life on Mars, and a wind sled have in common?

10 of May of 2019

Since February 12, Manuel Olivera has been getting back to his daily routine little by little. For two months before that, his life was far away from the offices at Ferrovial where he now spends eight hours a day. Over the course of those weeks, his workday was spent under a sun that never set, with temperatures at a high of -20º. He was steering a WindSled that made history on the Spanish exploration and research expedition to Antarctica.

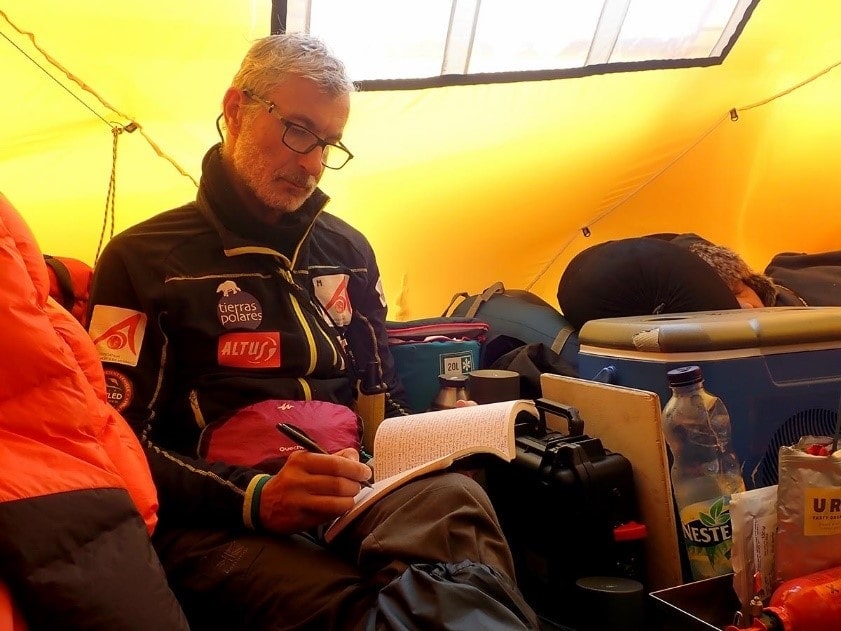

“The best thing about getting back to your routine is seeing that you can get back to your routine. Because when you go to Antarctica for two months, you totally forget what your life was like before that. You don’t even know what you were doing or what you left behind.” Back in Madrid, Manuel Olivera has been going back over his third expedition on board this polar vehicle dreamed up by explorer Ramón Larramendi. 53 days and 2,538 kilometers on the frozen continent, full of adventure and science.

Freeze-drying Asturian stew

Facing a nearly two-month mission in Antarctica takes a lot of logistical planning. The weeks before leaving Madrid were crazy for the team composed of Olivera, Larramendi, Hilo Moreno, and Ignacio Oficialdegui. “We get along well, even though there are things that come up at the last minute that you think are going to be easy, but they turn out to be more complicated. Like freeze-drying, for instance,” Olivera recalls.

“We put a friend in charge of them, someone who had gone on the previous expeditions. Now, he’s started a freeze-drying business for sailors. We were his pilot test. He didn’t get the food to us until the day we were leaving.” The wait and tension do seem to be worth the risk, given what was on the menu. Ten different meals, including Asturian stew, lentils with chorizo, and cod with potatoes.

The logistical prep work didn’t end in Madrid. The team was in Cape Town, South Africa, for almost a week finishing up the last touches. “Above all, sewing and gluing logos from sponsors on at the last minute, and buying food like rice, biscuits, and sugar.” Then came the move to the Russian base in Antarctica, Novolazárevskaya, where Hilo Moreno suffered a minor illness. That gave them three more days to get ready. “I felt relieved in some ways. It was stressful for me to think about how we would be in -25º temperatures in an hour,” Olivera explains.

A (really) white Christmas

A few days later, the temperature climbed up from -25ª. Or at least, it got up to the highest temperatures they could enjoy on their expeditions outside. Even though they don’t have the official records from la Agencia Estatal de Meteorología (AEMET), it was 40 above zero several times during the 53 days they were there for their mission. “For me, the hardest thing is that constant, intense cold. Your body gets used to it, but it’s hard, you have to stay alert, making sure your extremities are okay.”

Even so, they had a few minor issues with frostbite. During the first few days, they got burns on their cheeks and nose from not being careful enough. “You just have to leave a little bit of skin exposed, and it’ll freeze,” Olivera remarks. He was the only person on the expedition who had more significant problems, though they weren’t too serious. “I suffered first degree burns on the pads of six of my fingers. It happened on January 29, shortly before the expedition came to an end. From then on, I was really careful and cautious, avoiding certain tasks. The problem with having frostbite is that it gets worse because you still have to be exposed to the cold.

Over the course of the entire expedition, the team followed a strict routine. Nine hour shifts in teams of two steering the sled. Constantly checking clothing and temperatures. Regular, calorie-heavy meals. Six-hour rest periods. A routine they almost never strayed from, not even to celebrate Christmas.

“On Christmas Eve, we ended the day with two nine-hour shifts. Between thawing out water and heating the tent, it was already the 25th when we sat down to dinner,” the Ferrovial engineer recalls. “We had spaghetti with sausages, but it wasn’t a special meal or anything. We put on some Santa Claus hats. We had some special reserve rum they’d given us. And we shared a cigar that we could hardly finish. We also took out a fake little tree that was 30 centimeters tall, and we played some Christmas carols.”

150 kilos of scientific weight

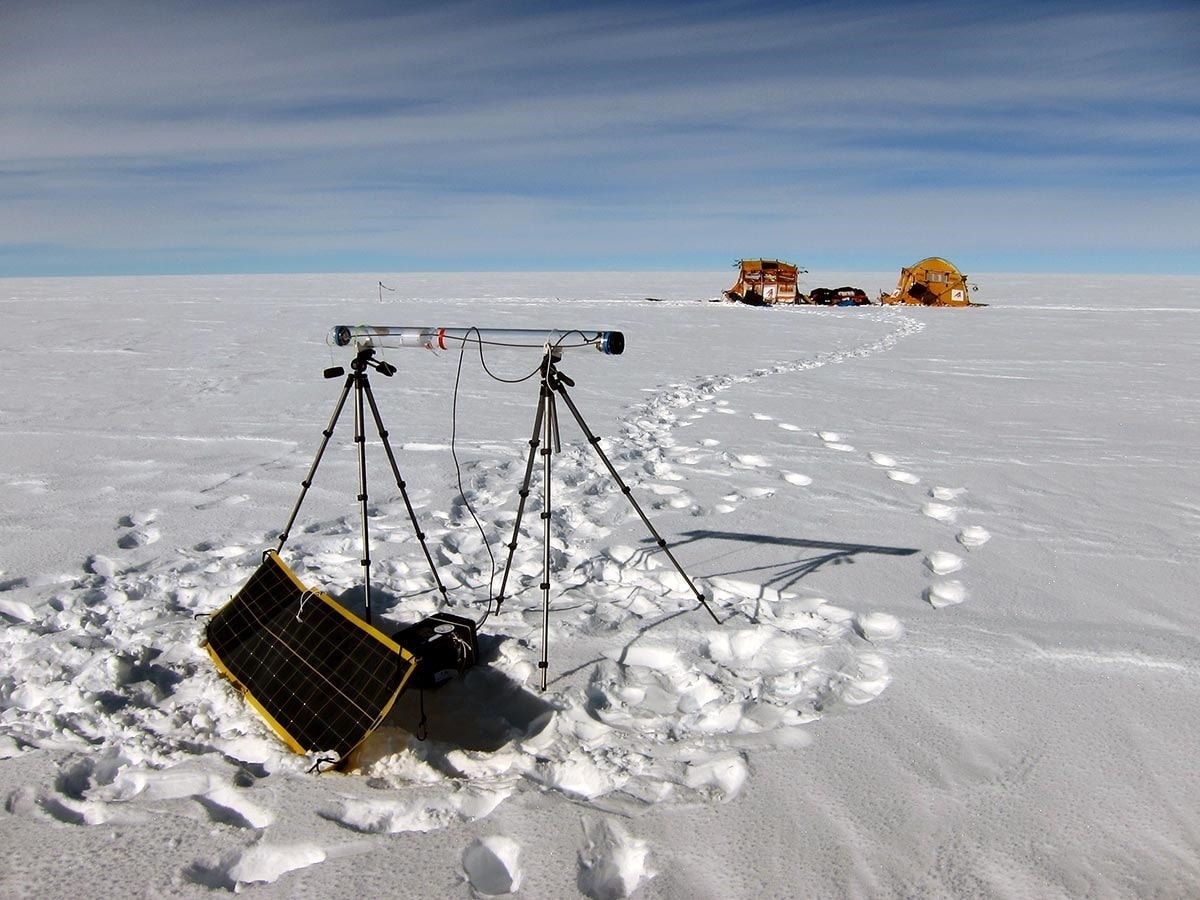

The main objective for the 2018-2019 Antarctica Unexplored mission was demonstrating the viability of the wind sled as a scientific vehicle. To do so, the team was responsible for handling 150 kilos of apparatus for taking measurements for a total of 11 different experiments. There still isn’t any official data, and it will be months, maybe even years, before the first publications are released.

“Right now, we have unofficial information. For example, we know that the data we collected for AEMET, which they were going to use to recalibrate climate models, isn’t going to be taken very seriously because we apparently didn’t use the sensors correctly,” Manuel Olivera explains. They also developed two experiments for the European Space Agency (ESA). One of them successfully confirmed that the network of Galileo Global Positioning satellites is working in Antarctica, and it is precise to within a meter.

Their work may also contribute to future missions to Mars. “The SOLID project consists of a robotic arm for analyzing the existence of life on the surface of the red planet. It’s an arm for the rover that goes around testing terrain and analyzing it to see if there are any biological remains.” That is, it’s an instrument to detect life on Mars. Right now, its tests on snow were used to find Antarctic microorganisms, something that will surely be useful for the Astrobiology Center at the Instituto Nacional de Técnicas Aeroespaciales (INTA), Spain’s space agency which is associated with the NASA Astrobiology Institute.

Science and technology have also been central to the expedition’s success. AEMET sent a two-day forecast every day, forecasts that were 95% accurate. Communication technologies allowed them to stay in communication with the project’s press director and the media manager for the mission, Rosa M. Tristán. It even gave them access to telemedicine services.

Ghost buildings that move across ice

The Wind Sled had two key points marked in red on the map of its route. Plateau Station, an American base that’s been abandoned for 50 years, and the Fuji Dome, which was the starting point on their way back. “We got to Plateau Station on the shift when Ramón and I were driving. It was very exciting. We saw the tallest antenna on the horizon, and we could correct our route,” Olivera recalls. The team had the original coordinates, but the base had moved 3 kilometers. Because it’s built on the Antarctic plain, the building moves as the ice flows toward the coast. “After 50 years, it’s moved 3 kilometers, about 60 meters a year.”

With Ramón Larramendi steering, the sled drew near the base’s field of antennae. But there was no building there. “There was nothing rising up above the snow. We only saw some sticks and old footprints going one way.” At the end of those tracks, a plastic skylight stuck out less than a hand’s width above the surface. The rest was buried under snow. “By digging around, we ended up finding a wooden cover. We pushed it open and sent Ignacio in to explore. We didn’t even know if he could breathe in there,” Olivera emphasizes.

But he could. Insides, they found a rectangular living space of about 200 square meters with a central hallway and rooms ready for them on each side. The base was occupied for four twelve-month seasons long by four soldiers, four scientists, and one leader, a medical captain from the United States Army. “They left in January 1969, but it looks like they were thinking about coming back. Everything was ready. The beds had clean sheets on them. There was a lot of food and stuff for cooking. They didn’t move out.”

After abandoning the ghost base, the days before they got to the Fuji Dome were full of anticipation. “And concern, because we might not get there. At ten days in, things were looking bleak. We were totally stopped for a few days. But then, favorable winds came,” Manuel Olivera explains. In the end, they didn’t exactly get to the top of the Fuji Dome or the Japanese base. They were 25 kilometers away. “There wasn’t anyone at the Japanese station. The good thing was that we got to Pleasant site with people and some commodities. But passing through another place like the Plateau Station wasn’t motivating for us.”

The last few days were full of a tense calm. Exhaustion and few words. “Even knowing you’re going to finish and that everything is going to be okay, the last days get hard. You just count the minutes until you’re going back and seeing your loved ones.” And that’s when they’d managed to fix one of the camping stoves that had broken and they were almost through with the mission as expected. In Antarctica, a simple stove means food, drinks, and heat.

A shower, two months later

When they got back to the Novolazárevskaya base and brought the expedition to a close, the team’s priorities changed. “The first thing I did was go straight to the bathrooms at the base to sit down on a toilet for the first time in 50-some-odd days. You miss that a lot, the comfort and the cool. Then, we went to eat, and after that, I took such a long nap that, when I woke up, they had all showered, and I missed my turn,” Manuel Olivera recalls. After 52 days without showering, one more week of the return trip to the hotel in Cape Town wasn’t going to make much of a difference.

“When it’s that cold, there’s no smell, you don’t sweat, it’s not unpleasant. The problem was that in Cape Town, there’s a lot of droughts and water outages. In our hotel, there was only a drip. I didn’t really shower until I got to my house in Madrid.” Even though they got back February 12, the mission still wasn’t over. There were still several meetings, like the one held with the minister of Science, Innovation and Universities, Pedro Duque, who expressed interest in incorporating the wind sled into Spain’s Antarctic program; there were also many press conferences.

Little by little, they got back to the daily grind. At least some of them. “Hilo has already gone off to be a guide in Greenland. That’s his job.” Manuel Olivera isn’t thinking about returning to the polar landscape in the coming years, though he will still be involved in the project. “I’ve come to a lot of conclusions for continuing to improve the vehicle. I have a family and a job, and I can’t go every year. But I’ll still lend a hand.”

There are no comments yet