It is not too much a stretch of the imagination to say that art, like the advancement of science, is a never ending endeavour for mankind. In part one of this article series we looked at the connections between abstract art and construction as expressed in ITER. In part two we continue our exploration of the world’s most unique site com gallery.

From the temporality of art…

In the 1960s and 70s an interdisciplinary group of international artists in Europe experimented with artistic performances that emphasised the artistic process rather than the completed artwork. What was artistic was the path that led to the object, not only the final product. This form of art attracted not only painters and sculptors but also composers, poets, designers, singers and artists working in other genres. It was the art of movements like Fluxus, the Happening and Situation Art. These new trends de-dramatised the artistic process and opened the door to impulsiveness and creativity.

The layout of the prefabrication areas and the storage zones are a goldmine of Fluxus and Happening references. Without the rigid demands of the final construction works, everything flows more fluidly. Objects are arranged irregularly and naturally, changing position and shape every day, while elements come and go. We tend to underestimate the importance of these places, but it is through them that we fulfil our objectives; it is thanks to our foremen and the people in the Logistics and Plant Departments that we know where everything is and that there are no parts missing.

In a natural evolution of these movements, time was incorporated into art as a form of expression as the era of the fourth dimension dawned at the end of the 1960s. One of the first controversial artists of this movement was Richard Long. The temporary lid of the central pit echoes this temporality, hinting at Long’s large pebble circles and spirals. The enormous round shapes laid down in the landscape by Long will one day disappear forever, as the temporary lid covering the central pit did in 2020. The lid was erected as a provisional screen to separate the work in the pit from the exterior and it was elevated in a heavy lifting operation. The steel lid was dismantled after the construction of the Crane Hall was completed to allow assembly of all the components that make up the puzzle of the Tokamak reactor proving its temporality.

Lifting of the temporary lid in the central pit reminds of the work Ireland (1967) by Richard Long.

Lifting of the temporary lid in the central pit reminds of the work Ireland (1967) by Richard Long.

Another British artist, Andy Goldsworthy, creates art in a changing landscape using perishable materials that he finds in the natural environment, such as leaves, sticks, flowers, stones and ice. Through his work, he seeks to convey the need to understand that nothing in life lasts forever. Goldsworthy has dedicated an important part of his creative process to holes that he builds using different natural materials. These holes symbolize the blaze of the energy present in a black fire. We can find a piece of Goldsworthy’s art not far from the site at the impressive Château La Coste in Le-Puy-Sainte-Réparade. When we arrive on the site platform, four black holes draw our attention.

Reinforcement of openings in the central pit reminds of the work Screen (1998) by Andy Goldsworthy.

Reinforcement of openings in the central pit reminds of the work Screen (1998) by Andy Goldsworthy.

These immense openings in the front wall on the L3 level, surrounded by orange circular plates, greet visitors entering the site. It is through these holes that men will replicate the energy of the burning sun, occupying the space with ducts and pipes that will pass through the imposing concrete walls.

Detail of concrete in L3M area reminds of the work Untitled (1986) by Ulrich Rückriem.

Detail of concrete in L3M area reminds of the work Untitled (1986) by Ulrich Rückriem.

…to the eternity of massive sculptures

Artistic expression grew larger during the last quarter of the century. Given the limitations of exhibition spaces, these artists are usually forced to exhibit their work outdoors in site-specific installations. It is impossible not to draw an analogy here with the massivity of civil constructions. The ITER project is unique in its widespread use of highly reinforced structures and high-performance concrete, with densities and properties that cannot be captured by the eye.

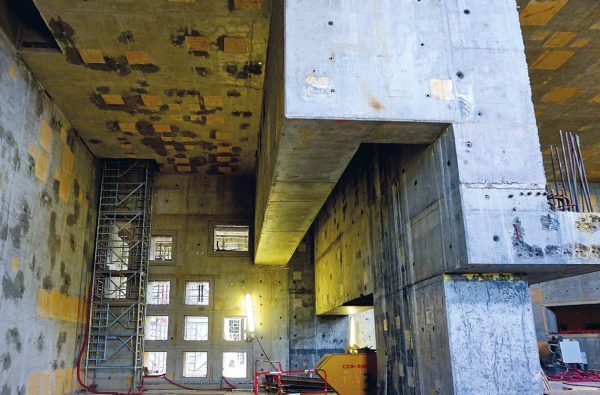

The abstract monumental sculptures of the 1980s are present all over the world. Eduardo Chillida’s sculptures made from concrete and steel are an example of monumental art. In his work, space is more than just an empty container. The shapes created by the concrete structures of the Neutral Beam Cell or L3 East level are overlapping and irregular, establishing an interesting dialogue between the mass and the void similar to that found in Chillida’s work.

Concrete structures in Neutral Beam Cell remind of the work Elogio del horizonte (1990) by Eduardo Chillida.

The ITER buildings are covered with a stainless-steel façade that gives a sense of mirroring or camouflage. A similar effect was sought by British-Indian artist Anish Kapoor with his large-scale abstract public sculptures in the early 21st century. Kapoor’s work deforms and inverts the landscape, creating a dialogue between the spectator and the space surrounding them. Kapoor’s Cloud Gate in Chicago aims to capture the life of the busy city by reflecting the surrounding environment, and it is these reflections that bring the artist to mind when looking at the façades of the buildings on the platform. Stainless-steel panels reflect the clouds and forests surrounding the ITER complex, landscapes that change with the seasons and evolve over time.

Reflections on the Building 13 façade remind of the work C-curve (2007) by Anish Kapoor.

Reflections on the Building 13 façade remind of the work C-curve (2007) by Anish Kapoor.

Kapoor’s work transports us to another massive sculpture by Japanese artist Kan Yasuda, Tensei Tenmoku. The name of the installation means “the door without a door” and it frames the infinite expanse of the Atlantic Ocean from the coastline of the Canary Islands in white Carrara marble. The doors are another component that plays a crucial role in ITER. The 46 large square openings of the Port Cell Doors will separate the toroidal magnetic reactor from the rest of the building and provide the only access from the bioshield walls to the plasma. The doors will subsequently be locked, enclosing the two spaces once they have been connected.

Coming full circle in steel

The concrete structures and equipment of the Tokamak Complex are crowned by another type of structure made from steel reminiscent of the art of Léger. The steel roof structure is a tribute to another American artist, Richard Serra, who attempted to challenge his audience’s perceptions with his massive steel installations. Observers can stroll around his curved steel plates, sensing the movement from inside and around his sculptures.

Serra’s installations reveal several parallels with the manufactured rolled profile beams in the Crane Hall. These colossal steel structures support one of the most impressive overhead gantry cranes in the world. The steel parts were lifted using large crawler cranes with super-lift counterweights, which are balanced with the same precision as Serra’s swing sets. In 2020, these delicate operations brought an end to the work of thousands of workers who helped to erect the concrete construction of the Tokamak Complex.

Steel structure in the Tokamak Crane Hall reminds of the work Trip Hammer (1988) by Richard Serra.

The footprints we leave behind

From the radicalism that cast off the chains of reality in the first few decades of the last century to the monumental abstract sculptures of the modern-day, humanity has continued to evolve at a steady pace. ITER represents a huge step forward in the technological and engineering world and we are privileged to have laid the foundations for this new industrial revolution.

Our project will soon be complete and, like in the art world, some of the knowledge we have acquired will be applied to other construction sites, reshaping the way in which our companies operate on other markets. What will remain with us forever is the exceptional human experience of being part of this project and my personal gratitude to all the members of the VFR community. This essay should be understood as greatly deserved acknowledgement of all those who contributed their commitment, perseverance, resilience and their hard work, in short, to bringing all the parts of the ITER buildings together.

Revealing the hidden art on the site to those who contributed to the project and making them proud of what they have built seems a legitimate way to thank them for their dedication.

There are no comments yet