The northern border between Spain and Portugal is littered with shared places. There are mountains and valleys with virtually the same names; rivers collect water on one side of the invisible line between the two countries and spill it onto the other. The Támega is one such river. It starts in the Sierra de San Mamede in Ourense and comes to its end at the Duero in the Portuguese town of Penafiel.

The Támega will also help Portugal end emissions of 1.2 million tons of carbon dioxide annually. That will let the country increase the total energy it can produce by 6%. This will be possible with a set of three dams, three connected hydroelectric plants, and a huge water supply for storing energy for the future.

A reversible plant

The Támega is dotted with mills. Several of the buildings, though now out of use, can still be found along both the Portuguese and Galician sides. These mills allowed many generations to harness the river’s power to grind cereals. Using the water’s kinetic energy is an ancient practice, and it can be traced back to the Hellenistic period in the West. Other sources point to earlier origins further east in the Persian Empire.

Watermills became very popular during the Middle Ages, but it was during the Industrial Revolution that humans learned to extract all of the water’s energy. From the first hydroelectric power station built in Northumberland (the United Kingdom) in 1880 to harness the potential energy of water, things have changed a lot. Today, hydroelectric energy accounts for 16% of all electricity produced in the world; it is the leading renewable source on the planet, according to data from the International Energy Agency.

The Támega River, where it passes through Amarante in Portugal. | Wikimedia Commons/Carlos Cunha

The idea behind the plants hasn’t changed much since 1880, though. These facilities are made up of hydraulic structures (like dams or pipes) and electromechanical equipment (turbines or generators), as indicated by the Institute for Diversification and Saving of Energy. The electrical power obtained is always related to the water flow and the height of the waterfall used. So how do you turn a dam and a river into a battery of sorts?

This is where reversible plants come into play. This type of hydroelectricity was developed shortly after the first plant in Northumberland was set up. This type of infrastructure can increase water’s potential energy by pumping water up to a higher reservoir, usually during times of low electricity demand.

When demand rises again, water is released from the top, generating more energy than was originally needed to transport it up. This is how a network of reservoirs can operate like a large water battery with the capacity to store energy for when it is really needed.

The great Támega battery

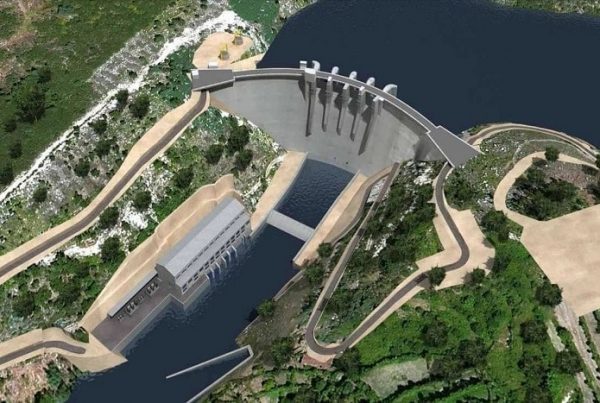

Proyecto del complejo hidroeléctrico del Támega.

The Támega hydroelectric complex, which Ferrovial is helping build, will have the capacity to generate 1,158 MW of power when it is finished in 2023. This will use three dams: Daivões, Alto Támega, and Gouvães, as well as three power plants. One of them, the power plant in the Gouvães cavern, will have 880 MW of power; it will be in charge of pumping water to the dam of the same name, which, in turn, will act as the large storage tank for the hydroelectric complex.

With this reversible plant, it will be possible to store water from the Daivões reservoir in the Gouvães reservoir, located 650 meters higher. So when there is excess production, some of that energy can be saved for another time when needed more. The main advantage of this reversible system is that the Támega hydroelectric complex will become a stable supply of electricity for the Porto metropolitan area.

When completed, the Támega’s so-called giga-battery will be capable of producing 1,766 GWh per year, enough to supply electricity to more than 400,000 homes. If necessary, the energy stored in the Gouvães reservoir could provide electricity for about two million families for a full day. The hydroelectric complex will also allow Portugal to diversify its sources for generating energy and stop importing 160,000 tons of oil per year; that oil consumption entails 1.2 million tons of CO2 emissions.

From the time it evaporates somewhere in the Atlantic or the forests of Europe until it cools down and precipitates in the San Mamede mountain range, seeping into the earth and filling the waterways of brooks and streams, the water completes its cycle, consuming a large amount of energy. Once in the Támega, a system of dams and turbines will be ready to harness some of that energy. The rest will continue to flow downstream to the sea, where it will all start over again.

There are no comments yet