The first elevators in the Eiffel Tower did not go into operation until May 26, 1889, eleven days after the tower was inaugurated at the start of the tenth Universal Exhibition in Paris. However, this didn’t tarnish its success: in the first week alone, more than 30,000 visitors climbed its more than 1700 steps, marveling at what was at that time the tallest tower in the world.

From its top, visitors celebrated its construction. Restaurants opened on the first floor, and the second even had a printing press where they made special editions of ‘Le Figaro’ that visitors took as a souvenir (and as proof they had climbed the famous Eiffel Tower).

On the ground, however, there were many others who didn’t see the structure in such a positive light. For years, the project was actually highly criticized by part of Parisian society. Some artists, architects, and journalists rose up against the Eiffel Tower, which they came to call an “iron monster,” a “tragic giant lamppost,” and a “watchtower skeleton.” They claimed it did not fit in with the architecture that had made Paris one of the most admired and most visited cities in the world.

From judgments to manifestos

The construction of the Eiffel Tower took two years, two months, and five days, and both on the date when construction began and when it ended (January 1887 and March 1889, respectively), it was expected to remain standing for 20 years. The news that an iron tower was going to appear on the Paris skyline for two decades was not always a welcome thought.

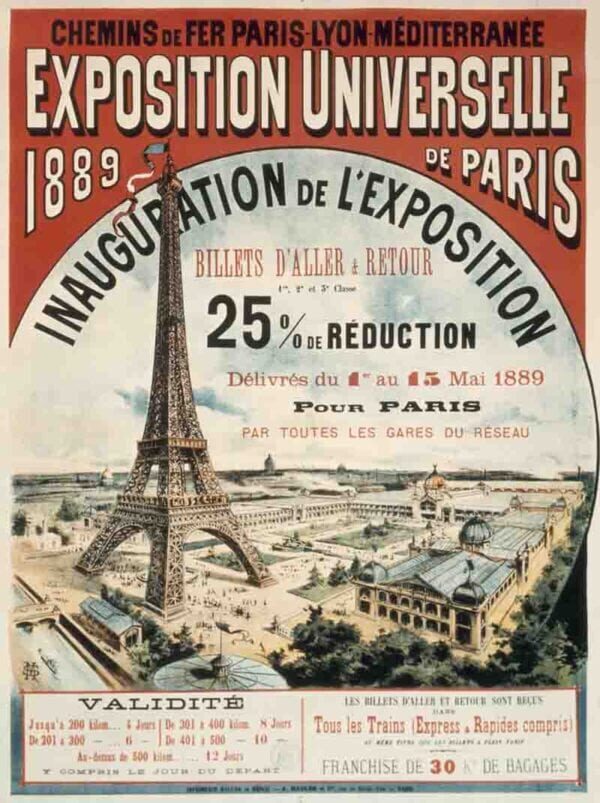

Poster of the Universal Exhibition. Wikimedia Commons.

Many of the neighbors who lived near the Champ de Mars in the seventh arrondissement of Paris tried to put Gustave Eiffel on trial. On February 14, 1889, a month after work began, the newspaper Le Temp published the ‘Artists’ protest against Monsieur Eiffel’s Tower’ on its front page.

This manifesto, which went down in history, was signed by such well-known and influential individuals as writers Guy de Maupassant and Alexandre Dumas (the son of the writer of the same name), the poet François Coppée, the painter William Bouguereau, and even Charles Garnier, the architect of the Paris Opera.

“We, writers, painters, sculptors, architects, and lovers of the beauty of Paris that was until now intact, come to protest with all our might, with all our indignation, in the name of the underestimated taste of the French, in the name of French art and history under threat, against the erection in the very heart of our capital, of the useless and monstrous Eiffel Tower,” the statement read.

Its authors considered the tower a disgrace to the city, a “tower of ridiculous vertiginous height… a gigantic black factory chimney that “even capitalist America would not want.” All of them – and many others – believed that it would bring an end to the beauty of Paris and that it would turn tourism away from the city forever.

Architecture in the spotlight

One of the most heavily criticized points of the Eiffel Tower was undoubtedly its size. When it was built, the tower was 312 meters high (today, it is 330 since an antenna was added), making it the tallest building in the world until the Chrysler Building went up in New York 41 years later. It is 125 meters wide, and its metal structure, made up of more than 18,000 pieces of iron, weighs more than 7,300 tons.

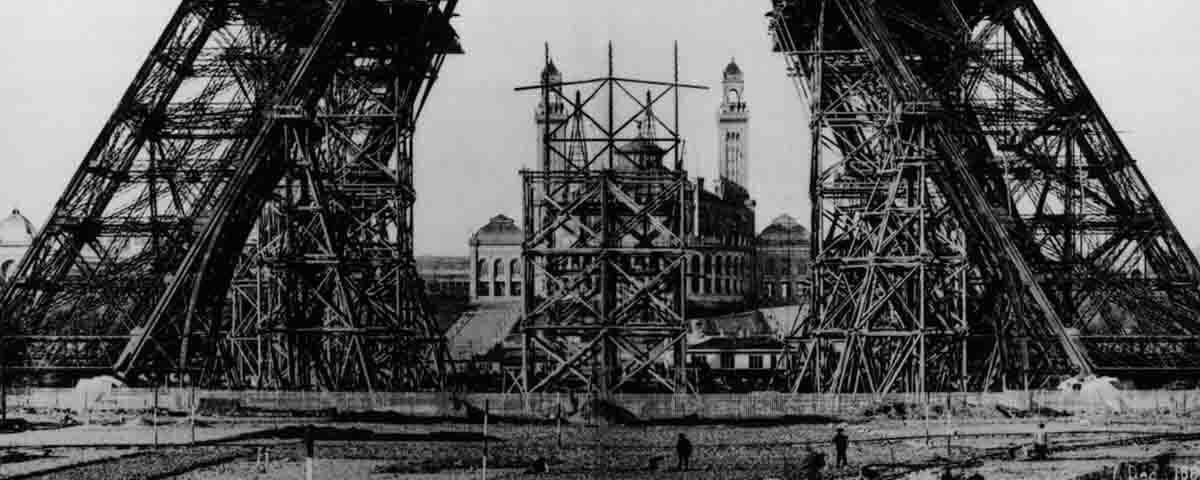

Structure of the Tower. Eiffel Tower Press Paris.

These figures were so impressive for the time that even some architects presented their doubts about the possibility of this construction. The magazine La Construction Moderne, for example, criticized the viability of the tower, especially its elevators.

As Bertrand Lemoine, French architect, engineer, and historian author of the book ‘The Eiffel Tower’ explains, Gustave Eiffel and city authorities always defended the viability, aesthetics, and future of the tower. The engineer compared it to the Pyramids of Egypt in the sense that they are both large constructions that symbolize overcoming technical difficulties.

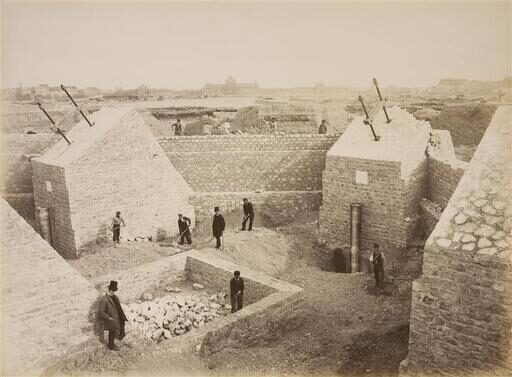

Construction of the tower’s foundations. Léna (Wikimedia Commons)

“Are we to believe that because one is an engineer, one is not preoccupied with beauty in one’s constructions, or that one does not seek to create elegance as well as solidity and durability?” Eiffel wrote. “Is it not true that the very conditions which give strength also conform to the hidden rules of harmony?”

The tower’s second life

Despite the criticism, Eiffel was able to build his tower and bring a new aesthetic to Paris. Criticism gradually died down as the popularity of the structure grew, and the tower became a symbol of the city.

However, some of the most critical voices held their position as the years went by. This was the case with writer Guy de Maupassant, for one, who said that he really liked the cafe on the ground floor of the tower with the following words: “It’s the only place in Paris where I can eat and not see that hideous tower.”

The structure took on various practical uses. Eiffel turned it into a large radio antenna and the center of numerous technical experiments, which saved it from being demolished in 1910 when the contract that allowed it to stand ran out. It played an important role during World War I and continued to serve as an antenna until many years later.

The Eiffel Tower in the Champ de Mars. Il Vagabiondo (Unsplash).

Today, the Eiffel Tower receives more than 1.5 million visitors every year and is undoubtedly one of the most iconic, recognizable buildings in the whole world. History once again shows us how changes and innovation are not always liked or well-received, and the world of engineering and architecture is certainly no exception.

Main image: The tower under construction at the end of the 19th century. Eiffel Tower Press Paris.

There are no comments yet