The Crystal Palace of London and how it revolutionized the architecture of the time

03 of September of 2024

London, 1850. The advent of the industrial revolution led the major nations of the day to share numerous inventions and technological advances. And, after the success of the Great French Exposition, Henry Cole, royal adviser to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, persuaded them to hold a major exhibition in London to compete with the technological prominence of France.

This exhibition was to become one of the events of the century, attended by illustrious figures such as Charles Darwin, Karl Marx and Michael Faraday.

For this event, it was necessary to build a huge open-plan hall to house all the exhibits, inventions and technologies, and the old-fashioned buildings of the time, full of rooms, stairs and various nooks and crannies, were simply not up to the task.

For this reason, a decision was made to bring together the country’s preeminent experts to form a select group called ‘The Building Committee’, who decided to put the design out to public tender for a project to be built in an area of the famous Hyde Park. This with certain conditions:

As the exhibition was temporary, the building had also to be temporary. This meant the design had to be:

- Quick to build

- Easy to dismantle

- Cost efficient in terms of materials

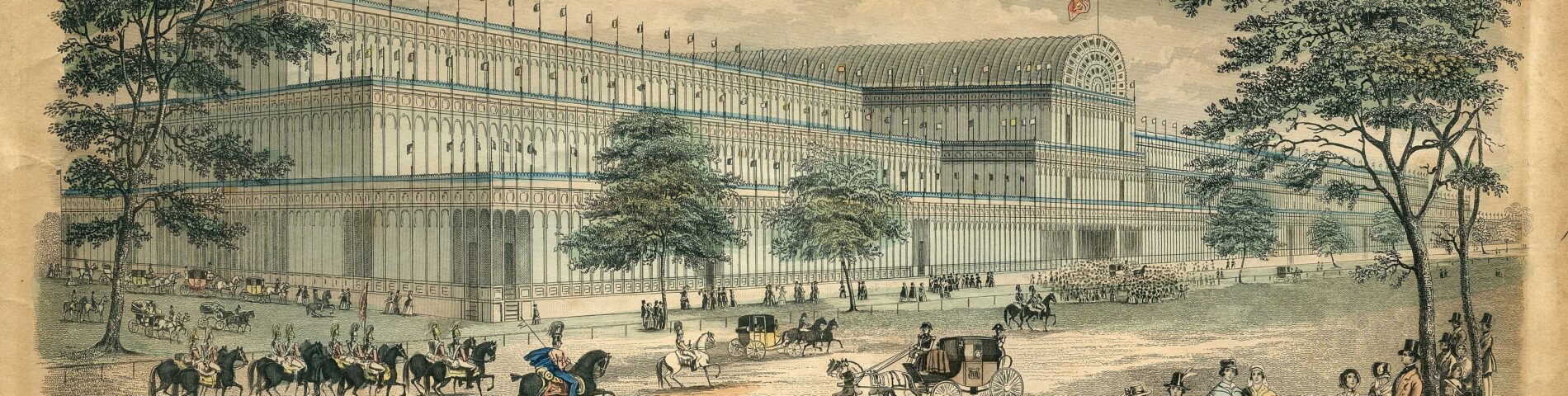

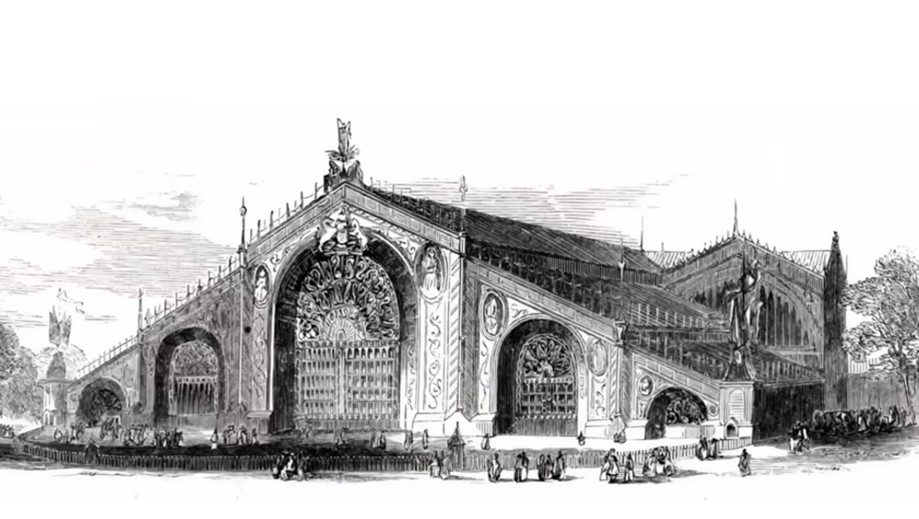

And, after a lot of work, this was one of the first buildings to be presented by architect Hector Horeau:

Taking into account the criteria of being very easy to build and quick to dismantle, this design would not appear to meet the requirements. And the designs that followed this one were not so different. The engineering necessary to meet the Committee’s requirements, while at the same time erecting an open-plan building large enough for a major exhibition, was a difficult challenge.

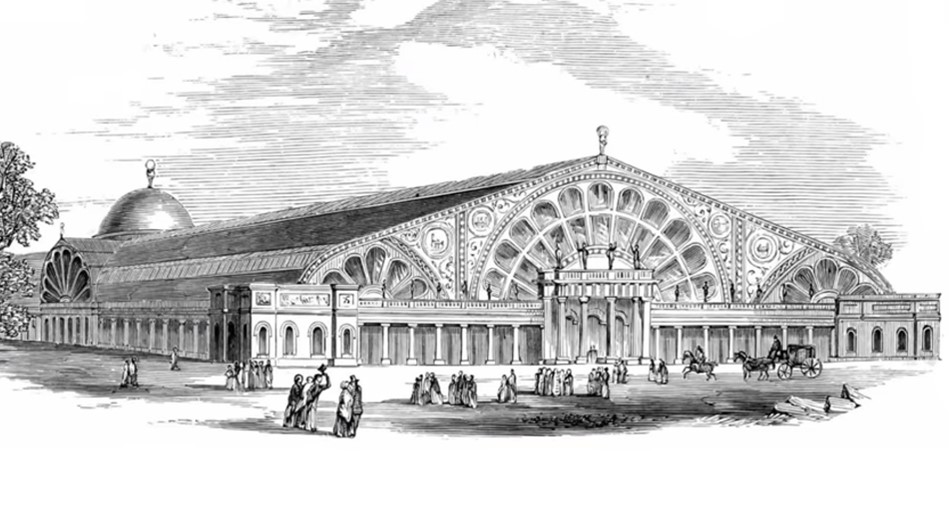

Here is another design:

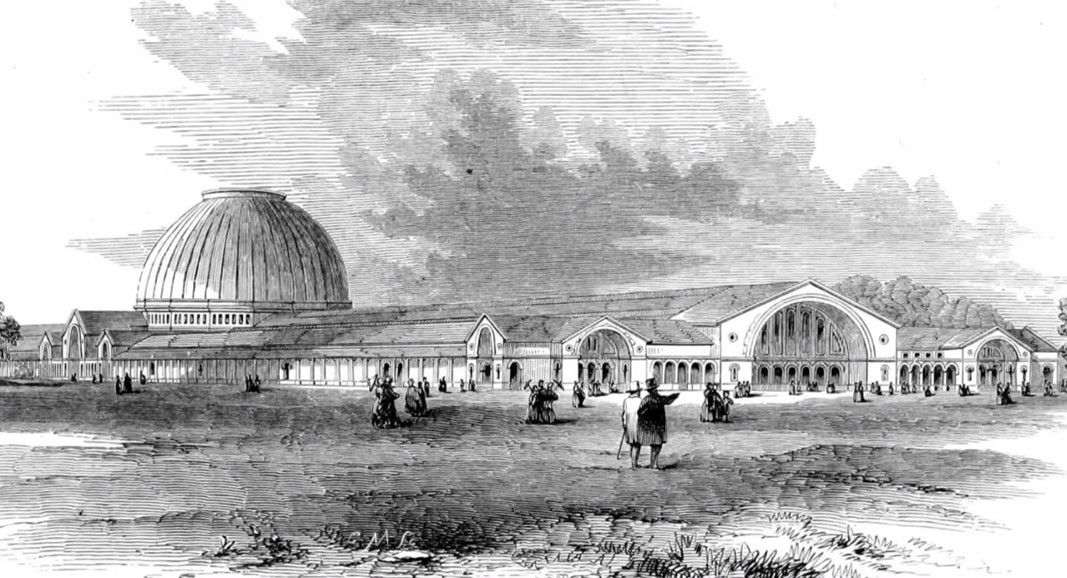

The committee, seeing the difficulties, even went so far as to make its own design, which, ironically, was even more complex than the others:

In light of the failure of previous proposals and the Committee’s brick design, which threatened to be costly, time-consuming and damaging to the esteemed Hyde Park, led London’s neighbors to begin to take issue with the project, even going so far as to denounce it before Parliament.

The press and popular opinion were beginning to jeopardize the viability of the project and of the exhibition itself, but the Committee was still looking for a way to solve the challenge:

How to design a building large enough while maintaining the light and space required for an exhibition of this caliber, but in a way that is efficient, quick to build, and easy to dismantle when finished?

After more than 200 proposals, it seemed an impossible engineering challenge for the architects and builders of the time. The building style in England prior to the 1850s was characterized by the use of traditional materials such as masonry and timber, as well as the application of traditional building techniques. This posed a major challenge for the design of the building that would house the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park in 1851, as a structure was required that would be large and strong enough to house the exhibitions, but also aesthetically appealing.

The solution? A palace of iron and glass

It was then that Joseph Paxton, a gardener and architect who had designed several greenhouses for the British royal family, came along. And it was his unique experience and profile that enabled him to come up with an innovative solution that no one else had even thought of: a design inspired by the structure of greenhouses, but much larger and stronger.

Its revolutionary design consisted of an iron and glass structure that allowed more natural light to enter the building and more open space. The structure was based on a modular system of prefabricated parts that were assembled on site. The construction of the building known as the Crystal Palace was completed in just six months and became a symbol of the Industrial Revolution and of the technological progress of the time. Paxton’s design was an architectural innovation that changed the way public buildings were constructed around the world. Its design became popular, and the public, and even Hyde Park’s own neighbors, came to love it.

Paxton also invented various efficiency systems for the building industry. Indeed, the Crystal Palace was innovative in many ways. Paxton used light and strong materials, such as iron and glass, to create a light and airy space. He also implemented natural ventilation and heating systems, which made it possible to maintain a comfortable temperature inside the building without using additional energy. These energy efficiency measures were revolutionary for the time and laid the foundations for sustainable building construction in the future.

The exhibition was a success. For the people it proved a privilege to move from large, partitioned buildings to a magical experience of light and space.

And when the exhibition was over, the palace was such a success that there was some resistance to its disassembly, with a decision made to transfer it to another area of London for the pride and enjoyment of London citizens. However, on 30 December 1866, a fire destroyed much of the building, leaving only the ruins. Although there were no fatalities, the fire caused great damage to the structure and it took several years to rebuild. The Crystal Palace of the Hyde Park Grand Exhibition was finally demolished in 1875. Despite the dramatic ending of the building, this iron and glass structure became an architectural landmark and an example of the new building style of the time.

The Great Exhibition at Hyde Park in 1851 was a turning point in the history of construction, showing the world the latest innovations in materials and building techniques. This event marked the beginning of a new era in architecture and construction in England, having an impact on other parts of the world.

A Crystal Palace in Madrid

When in 1887 a building was request on the occasion of another exhibition, the Philippine Islands Exhibition, architect Ricardo Velázquez Bosco decided to follow Paxton’s idea and use the same style of iron and glass construction that had been used in the London building, by then known as iron architecture. The idea was also to create an open and bright space in which the mineral and rock samples could be displayed clearly and visibly. The result was an impressive construction built in just five months and which today is one of the most iconic sites in the Retiro Park (see also this post on some of Madrid’s most iconic buildings, including the Palacio de Cristal).

The building stands out for its unique and elegant design, with a metal and glass structure that gives it a delicate and majestic appearance. And although it was built for the exhibition, the building has remained for posterity. Moreover, because of its beauty and size, it has witnessed historic events such as the proclamation of Manuel Azaña as president of the Second Spanish Republic in 1936.

The Palacio de Cristal of Madrid currently houses temporary exhibitions of contemporary and modern art from the Reina Sofía Museum and is one of the city’s main tourist attractions. Its location in the center of the park makes it an ideal place to enjoy nature and culture at the same time.

There are no comments yet