In the 1890s, construction on the Woman’s Building divided Chicagoan society. While some praised the initiative – a building that illustrated the role of women in history – and the architectural beauty of the construction, others saw it as a means to uplift the suffragettes and get women to occupy a space that, up until then, they had been barred from.

The Woman’s Building was designed by Sophia Hayden Bennet, a young architect who was only 21 years old at the time. She saw her project modified, criticized, and judged. Despite the fact that much of society applauded her, the criticism ended up weighing more heavily on her than the praise, and she decided to abandon professional architecture forever.

The first female architect at MIT

Sophia Hayden Bennet was born in 1868 in Santiago de Chile, but her family soon moved to Boston (United States), where her father was originally from. She soon developed an interest in the design and construction of buildings. After finishing high school, she enrolled in the architecture program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Before spearheading the design of the Woman’s Building, Sophia Hayden Bennet had already engraved her name in the history of architecture: she was the first woman to graduate in this field at MIT (where she shared the blueprint workshop with 90 other classmates, all men), and she did so with honors. Despite this, her first attempts to earn a living as an architect didn’t go well: tired of having doors shut in her face, she began working as a technical drafting teacher at a Boston high school.

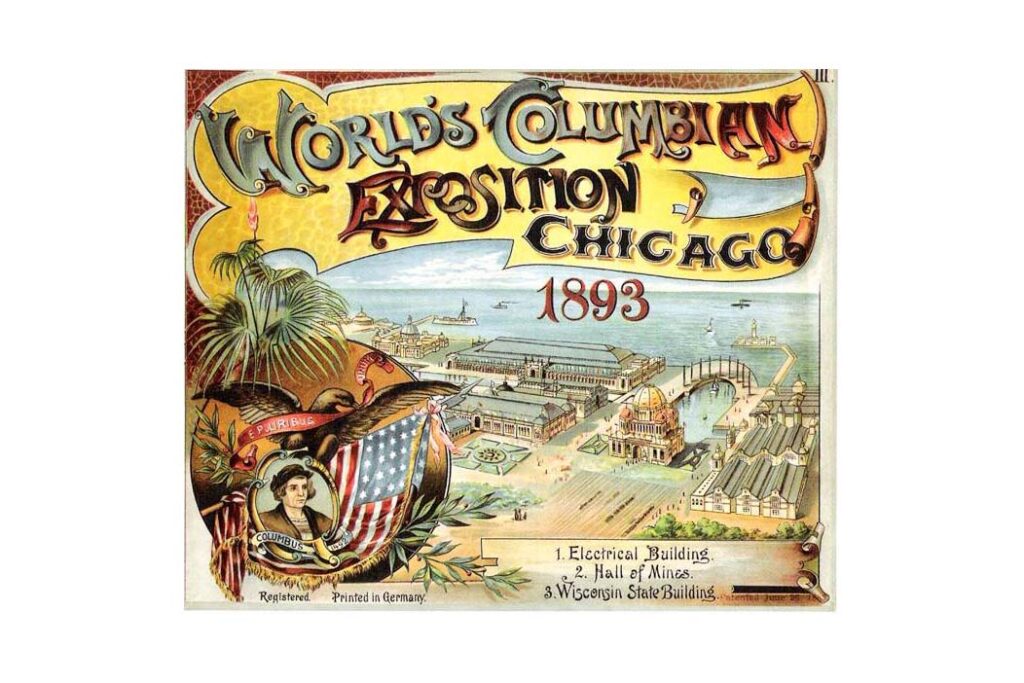

However, another woman’s work would soon give her another opportunity in the field of architecture. In the early 1890s, the City of Chicago was preparing the World Columbian Exposition, which commemorated the fourth centenary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival to the American continent and the advances that Western civilization had made since. It was decided that one of the many pavilions at the exhibition would be dedicated exclusively to the achievements of women throughout history.

Poster for the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Wikimedia Commons

At the forefront of this project was Bertha Potter Palmer, a wealthy and well-known patron of the arts. She decided that not only would the building’s contents be dedicated to women: women would be the ones designing it. Of all the projects submitted to make the Woman’s Building a reality, she chose Sophia Hayden’s.

From plans to polemic

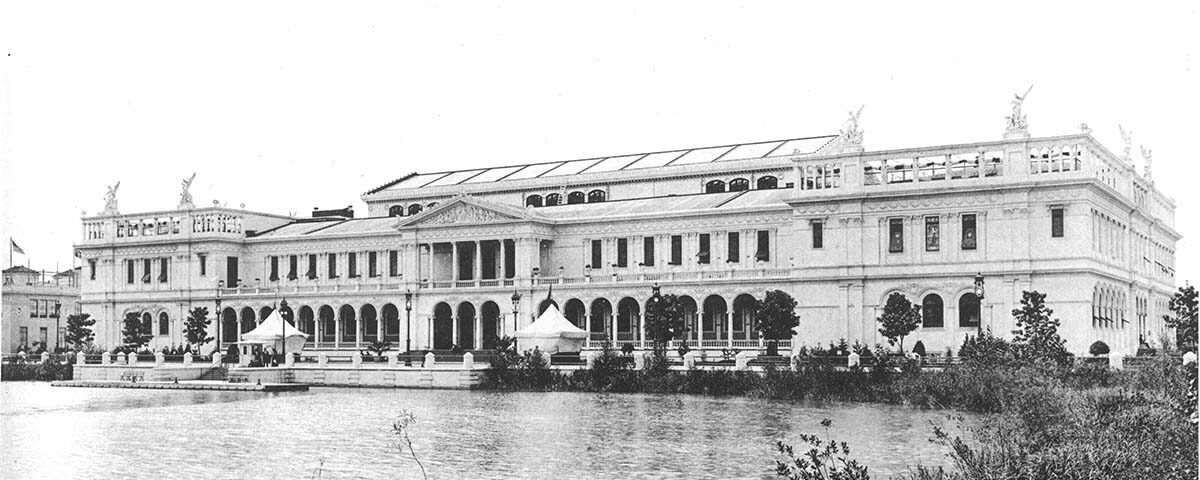

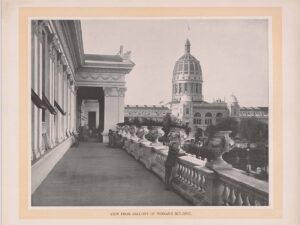

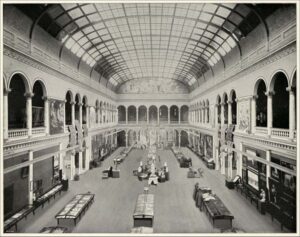

Hayden’s project sought to bring life to an Italian Renaissance-style building, with a large portico with Greek columns and an open, bright central space that was two stories high. This was an adaptation of her graduation project at MIT, which had earned a good grade. However, throughout the construction process, the initial designs received significant criticism and ended up undergoing many modifications.

Part of the exhibition’s organizing committee, led by architect and urban planner Daniel Burnham, deemed this building project irrelevant. Hayden’s style was also interpreted as feminine, and as such, it was less appreciated than those by other architects participating in the exhibition. Many other people from the world of art and architecture, however, defended Hayden’s work and role.

Balcony of the Woman’s Building. Ball State University (Wikipedia).

This division carried over to society and the press. Some articles of the day illustrate both the criticism and compliments of Hayden’s work, something that contributed to the debate that reverberated on the streets. “This composition is the work of a professional architect, and not, as some would have us believe, that of an architecture student,” reads an article signed by H.H. Bancroft in ‘Book of the Fair.’

In other publications, however, the work was described as a “women’s whim” that would end up being “a place to have tea under the shade of Japanese silk” or “a place where women can show the things they’ve done since men have allowed them to do them.”

The criticism, pressure, and difficulties that Hayden faced contributed to her growing frustration. Her detractors interpreted this as a sign of weakness and her inability to supervise the construction.

The short life of the Woman’s Building

Finally, despite these obstacles, the building was inaugurated in 1893. It was almost 120 meters long and more than 21 meters high. One of its most distinctive features was a large skylight that let the light from outside into the main room. On the sides were rooms intended to house exhibitions, conference rooms, and offices, among other purposes. One of its most outstanding features was its library, where thousands of books written by women were shelved.

Interior of the Woman’s Building. The Field Museum Library, Wikipedia.

For several months, the Woman’s Building hosted numerous debates and meetings between women from different fields, as well as international art exhibitions. Today, though, we can only see this building in photographs and illustrations from over a century ago: it was demolished in 1895 after standing for only two years.

Hayden was honored by the female members of the Woman’s Building committee. However, the exhibition’s organization paid her $1,000 for her work, some three to ten times less than what her male colleagues received. After this experience, she left her career as an architect forever. She dedicated her life to art and was a very active member of local societies that championed women’s rights until she died in February 1953.

Main image: The Woman’s Building at the World Columbian Exposition. Wikimedia Commons.

There are no comments yet