Roads that generate electricity: cars create energy at 70 miles an hour

02 of November of 2016

History is the time when someone says: “that cannot be improved”, and gets it completely wrong. It happens all the time: when it was believed that tar would be the future of our motorways, and when it was later taken off our roads. Or even when some years ago we included recycled materials in roads.

We believe that what has become the norm will be eternal and unchangeable. That existing building methods will remain unaltered for decades or even centuries. But technologies seldom have the chance to reach their peak efficiency level before a new one comes along and takes their place. And we’re now on the verge of experiencing the most amazing synergy: the moment when motorways start generating their own electricity.

Why is it necessary for roads and motorways to generate electricity?

We are living through a historic moment in time. Charging a hi-spec device such as our phone only costs a few pennies per year, but there are now processors in practically every single one of our gadgets, and the clear trend is towards connecting them all through the internet of things.

And it’s not only smartphones. It’s the fridge, the thermostat, our earphones and loudspeakers, chargers, and even lamps (LED drivers are fitted with chips that use some energy).

Everything we connect to the Internet now or in the future will require a permanent source of power. Source: Pixabay/jeferrb

In other words, we have fragmented large localised power consumption (for example, the light bulbs we were using last century) into thousands of delocalised micro consumption points. And here’s where energy-generating roads come into play: in doing away with the cost of transporting electricity.

In order to power up a light bulb located 15km from the nearest town, you need a power line of 15km up to that bulb. In other words, a continuous line of cable with the corresponding posts every 10, 12 or 20 metres, with all the associated costs: for laying the line, plus operation and maintenance costs, together with losses through inefficiency.

For the longer a power line is, the more energy you need to pump into it to get the required amount at the other end; the copper cable must be thicker to cope with this increased power; and more insulation material is required. This all means a greater cost and greater environmental impact. To say nothing of the intermediate transformer points needed, which further reduce the efficiency of the whole system.

Street lighting. Source: Sergey Zolkin

If each lamp post, traffic light, signal or emergency point had its own generator on the motorway, activated and fed by the actual cars using the motorway, a large part of these costs would be eliminated, repair would be easier (almost a case of plug&play), installation and maintenance costs would be reduced, and it would all be better for the environment.

But how can roads generate electricity?

OK, so we’ve seen that something like this is necessary. But how do we go about it? Where do we get the energy from, how do we store it and take it to where it’s needed? How do we transform it into electricity? Although research is ongoing in many different areas (solar roads, or wind farms closer to points of use), here we’ll talk about two relatively new technologies:

Piezoelectric pumping

Although it may sound rather strange, we’ve all held a piezoelectric generator in our hands at some stage: the loudspeaker of a greetings card. This is a gadget that emits a specific sound upon application of a particular current and voltage, which cause deformation. This deformation is what produces vibration and a sound in the air.

How a piezoelectric generator works. Source: Wikipedia

But if the process is reversed, and the piezoelectric element is deformed in a specific way, current and voltage are generated. This can, for example, charge a battery. Piezoelectric pumping is a type of energy generation by impulses which consists in deforming or pressing a piezoelectric material a number of times per minute to charge a battery.

Given that the greater the mechanical force (weight) applied to the piezoelectric element the more energy is generated, it would be a good thing to use on roads, where force would be applied dozens of times per minute. The UK’s Environmental Transport Association proposed a mechanism which generates 400 kW per kilometre and has been designed and tested in Israel with excellent results.

The system uses and generates power from weight, movement, vibration and temperature changes. And this means that it can also partially capture the wind.

A wind mine on each road

If piezoelectric generators can capture micro variations in air pressure, there is loads more energy in the form of high-speed winds. Just what cars moving along a road generate, in a similar way to the waves that are created by a speedboat moving through the water.

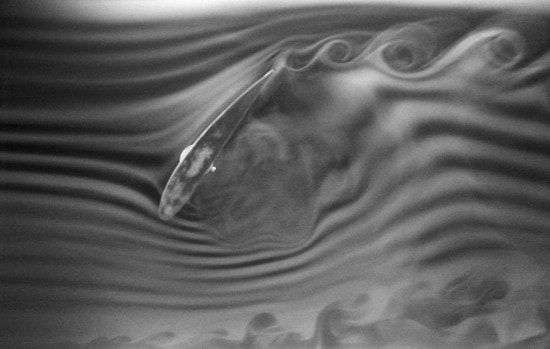

Waves created by an airfoil profile (such as an aircraft wing) when moving left in a straight line. Any object, when moving through the air, leaves behind it pressure waves of different shapes and speeds. Source: Wikipedia.

In 2009, Pennsylvania State University carried out a study on the potential design of roadside vertical wind turbines to capture the waves created by passing vehicles, an energy that is currently going unused. This invention, which would be a substitute for the concrete barrier used as a road median, utilises such energy.

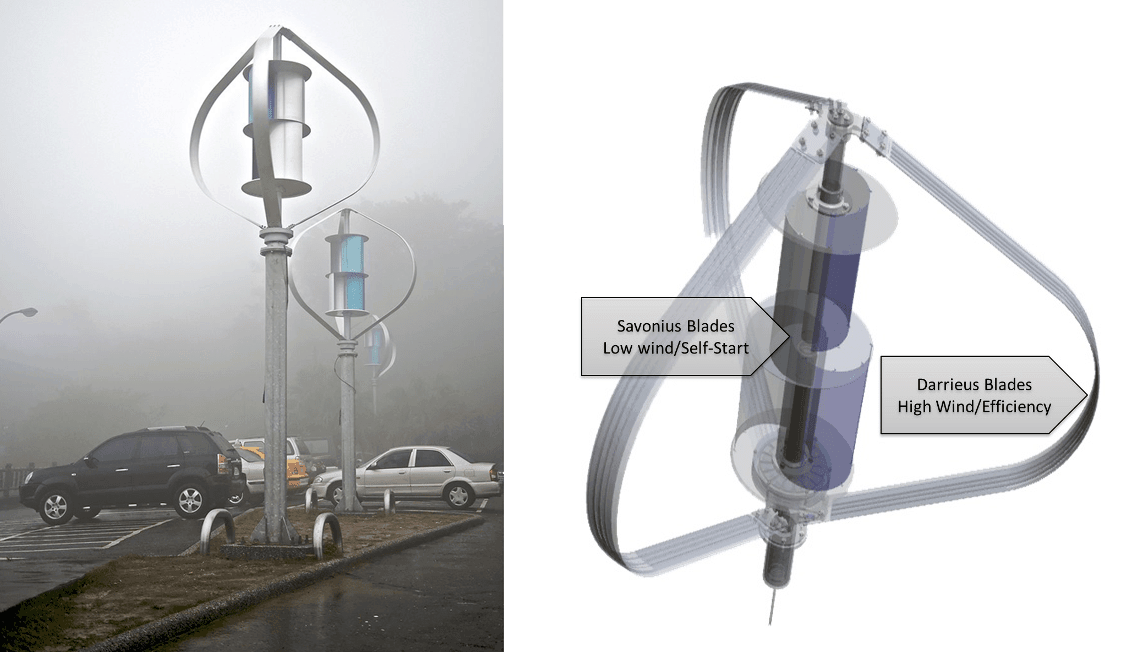

Darrieus-Savonius wind turbine (Taiwan, 2009). Source: Wikipedia

In that same year, the first tests of a turbine combining Darrieus blades (the three external blades) and Savonius blades (the seemingly solid blades in the centre) on a single turbine were carried out in Taiwan. This system, which has a cost of around £1000, recovers around £300 per year, with each unit generating an average of 5kW annually, so that it pays for itself in less than four years, and has an estimated useful life of ten. In other words, for 60% of its useful life it becomes a clean energy generator at zero cost.

These turbines obviously do not capture only the wind generated by fast-moving cars, but any wind there is. They can be installed along the motorway median (and are therefore easy and cheap to access).

As an example, if the turbines were set up all along the Madrid-Barcelona motorway, at a moderate distance between them of say 10 metres, the cost of all the turbines for the project would be of around 76 million Euros. But this cost would be recovered in less than five years, with 325 MW generated for the power grid. After this time, a second wind farm could be started along the Madrid-La Coruña road, financed by the savings from the first motorway farm.

A motorway median, a space which is today unused. Source: Wikipedia.

This type of distributed wind farms could be the future, given their advantages vis-à-vis large (5 to 10 MW) turbines, particularly due to the much reduced transport and maintenance costs. A large, broken-down turbine involves high costs in terms of time and money for repair, and spare parts are also expensive. But a small turbine can be substituted for another in a matter of hours.

Moreover, the 65,000 turbines which would be required on the Madrid-Barcelona motorway, to continue with the same example, needn’t be of the same brand or model. Industry has shown that the manufacture of small numbers of units by a small number of brands favours neither competition nor technological advances. A windfarm with a hundred different turbines is the perfect laboratory for ongoing improvement.

And the environmental impact is extremely low:

- They use a space which is available but currently unused, so there is no need to encroach on large swathes of countryside.

- Noise production is practically nil, especially compared to traffic noise.

- The danger of harm to wildlife, especially birds, is considerably reduced due to the low speeds at which the blades rotate.

- The synergies created with mid-voltage electricity lines located close by could perhaps even eliminate the need for the current electrical pylons grid.

In 2010, Spain had 11,432 km of roads and motorways. Using only this system of electricity generation, they would yield close to 5,700 MW, a tenth of Spain’s record of 45,450 MW in 2007, which still stands as the country’s highest consumption peak.

And all this without counting the potential for a mixed system, with solar panels covering part of the median under the wind turbines (amongst dozens of other possible alternatives to fossil fuels). Without a doubt, there is still a long way to go in the generation and use of energy, with new green systems emerging almost every year for generating energy in a more environmentally friendly manner.

In 2014 Deutsche Bank submitted a report which showed that Spain had reached grid parity with photovoltaic panels, as had 18 other countries. Green energy has only been around for a few years, and solar energy has already proved cheaper than nuclear or fossil energy over a period of two years, and its cost continues to drop month on month. Roads have a lot to say in the future of our energy.

Cover photo | Martin Ezequiel S.

There are no comments yet