We live in such busy times that when we come up against a problem, we don’t stop to think whether someone may have already solved it before us. And so when we are asked to “design a building which reduces energy loss to a minimum” we quickly reach for a 19th century handbook, when perhaps the problem had already been solved way back in the 10th century.

It has taken us a while, but we have finally realised – at the cost of the air we breathe – that in recent decades, architecture has strayed far from adaptation to the environment in its urge for standardisation. It is not possible to use the same type of building everywhere in the world and expect it to be efficient and sustainable, and yet that is precisely what we have been doing for the last 100 years.

Perhaps we should stop a moment, look back at traditional architecture, and ask ourselves why no climate control devices were necessary back then. Or we could perhaps even label it bioclimatic architecture to make it look more attractive (or #ArquitecturaBioclimática, when sharing on Twitter).

Standardisation is cheap, but it comes at a very high cost

The expression “like hot cakes” comes to mind when we look back and observe the moment, way back in the 19th century, when all European buildings started to be built in the same way. Although quick to make and affordable for the pocket, hot cakes have a high calorie cost which few of us can afford in the long run.

Something similar can be said about the buildings which were mass-produced to the detriment of the environment, when pollution was not yet a problem. Fifty-six percent of our building stock went up well before any energy standards existed, and 39% was built under standard NBE-CT-79 – which already now seems out of date when talking of energy efficiency.

As a result, even when the last of our combustion vehicles leave the roads for good to make way for electric vehicles, our buildings will continue to emit greenhouse gases for decades to come. That’s the cost of affordable buildings.

Building on snow and on desert sand

Nothing is clearer than the contrast between extremes, so let’s begin by looking at two of the planet’s most extreme habitats: the Equator and the North Pole. The latter is where the Inuit people live, albeit now increasingly in blocks of flats.

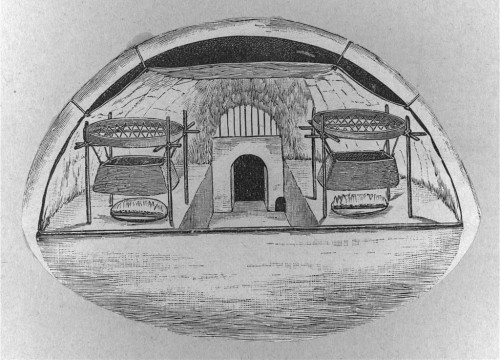

The picture above shows a region lying at a latitude of 65N, and therefore well used to blankets of thick snow even in the warmest summer months. At least, that’s what it was like in the 19th century, when Inuits built their igloos at temperatures below freezing, on snow which was at 0ºC. And the question we all used to ask ourselves as children: how can they survive in there, even if they are sheltered from the wind?

Contrary to what we here in the west assumed, the inner walls of the igloo are not at 0ºC, but rather closer to 2ºC. And it may seem surprising to learn that the air inside was at a temperature of around 16ºC (290K). This meant that these northern peoples could shelter inside for the night at temperatures which were very similar to those of a fresh summer morning in a Mediterranean climate.

They achieved this partly by covering the inside of the igloo –made with blocks of highly compacted snow – with a layer of cloth for insulation. It was rarely necessary to use energy to heat the igloo. (What has modern construction to say to that!)

The other extreme is a home in the equatorial desert, which is subjected to very high temperatures during daylight hours – more than on any other place on Earth. For example, a Tuareg home, which is basically made of cloths hung in such a way that they ward off the sun and prevent the entry of hot air and, more importantly, the sand carried by the desert winds.

Anybody who has ever stood under a sunshade (or under a leafy tree) will know what it is to immediately feel a radical drop in temperature, followed by an even greater drop in the sensation of heat. Something which is achieved in the hottest place on earth by using nothing more than mere carpets. We in the west would need an air conditioning unit.

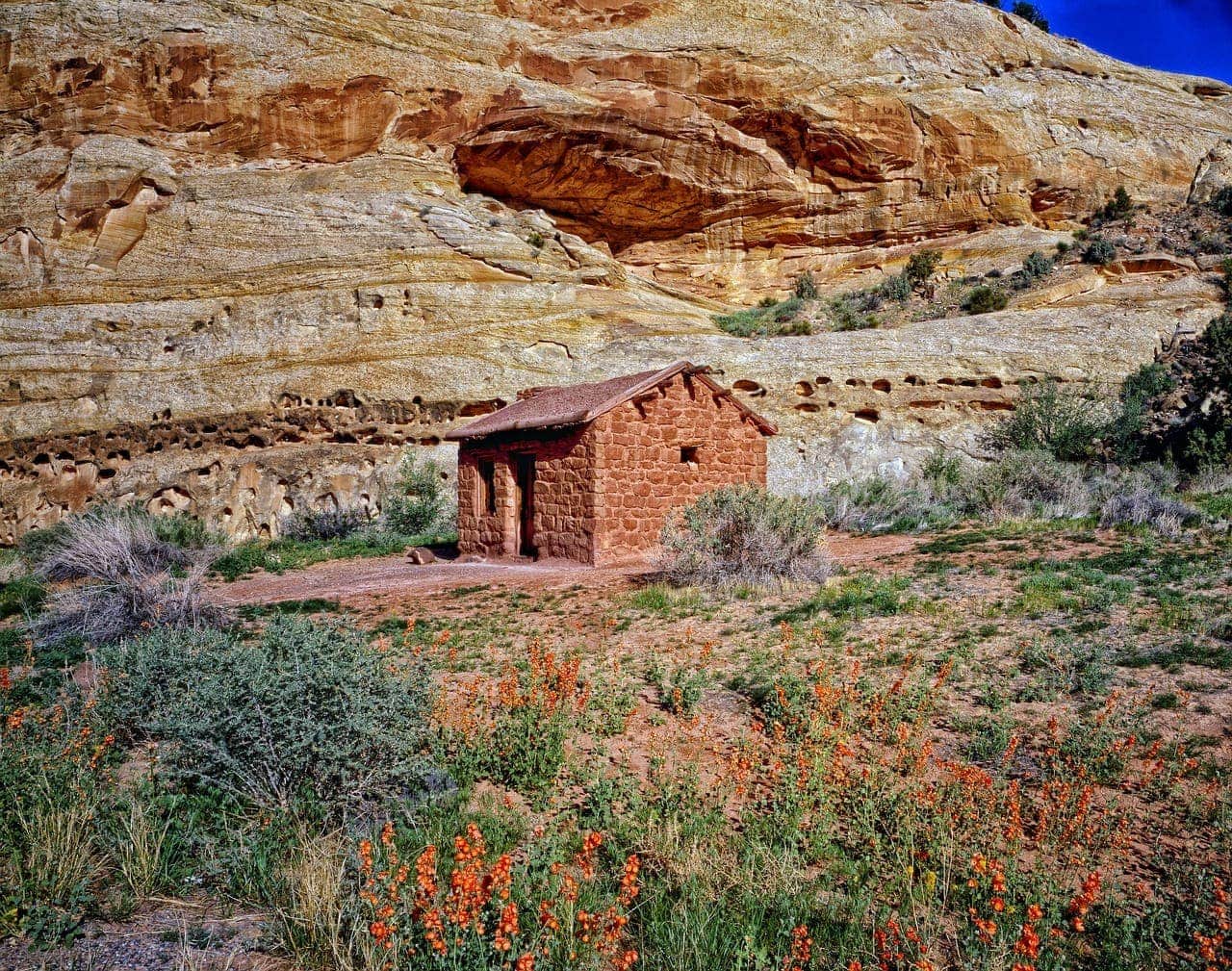

And right up against these hot Tuareg sands, the sedentary population of previous civilizations built using thick walls. People tend to ask: were they not roasting hot in such buildings, without air conditioning? And the answer, obviously, is no, or they would have built differently.

The people living in this and other fortified cities used thick walls not just to protect themselves against their enemies. Heavy, dense, thick walls have a high thermal mass and, despite absorbing much of the outer heat which they then give off inside, they do so very slowly: in 24-hour cycles, with a time lapse of approximately 12 hours. Which meant that when the sun stopped shining on the outer walls and these started cooling down, the inner walls started to give off heat, thus warming up the colder air and protecting the residents against the colder night-time temperatures. In the morning, the walls were cold again, but the sun soon started warming them up.

It seems rather striking that none of the buildings we have mentioned need a heater or a cooling unit. And we could of course provide more examples. One (or several) per region of the world. And how many of these examples are we copying in our buildings? None, of course. Please, we’re a developed civilization, we use climate control.

Why do we use climate control?

We have illustrated several extreme examples. Most people in Spain don’t have to put up with temperatures of -30ºC or 45ºC for more than a few minutes per year. (Or more, perhaps, if we travel to the exotic indoor world at the bottom of our freezer.) On top of that, a large proportion of the world population lives close to large expanses of water (seas and oceans) which soften and buffer extreme temperatures. In other words, things are much easier for us than they are for the Tuareg or the Inuit peoples. So, why are we using climate control?

The basic reason is that we have standardised our buildings to such an extent that we apply the same design the world over. A design which is perhaps ideal for a narrow region of latitude close to the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, for short periods of the year, but very inefficient for the rest of the year and the rest of the world. We use the same architectural design in much the same way as a master key is used in many doors: it works pretty badly in most, and even worse in a few.

A different construction design would need to be used for every inhabited region of the world. Or almost for every valley, even if the surrounding valleys use similar designs with few variations. The problem is, obviously, the cost of designing and putting up the buildings, even if they had the same shape as they do now.

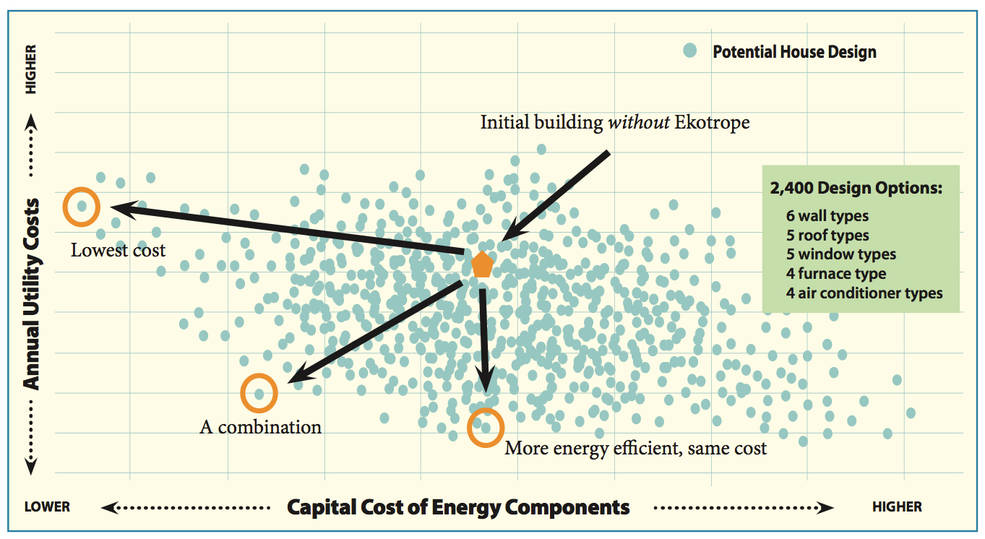

The above diagram (from NASA´s IA Ekotrope project) shows the energy cost of use relative to the energy cost of construction based on a series of parameters for homes shaped as a parallelepiped:

Though disperse, the point cloud (where each point is a home) shows that the higher the initial energy costs (homes more highly adapted to a specific area), the lower the energy costs for decades. Our buildings are located to the left of the graph, where the orange circle is. They are affordable, but their Annual Utility Costs are very high because of the need for climate control.

How should we build in Spain?

There’s no need to travel the world to see the complexities of building according to the climate. Our cultural diversity, of which we can feel rightly proud, is to a considerable extent due to temperature differences, although the cultural and climate differences from north to south, from seas to oceans, from deserts to inner mountainous regions, amongst others, would be hard to distinguish from the shape of our buildings. Because they are all the same.

Yes, granted that different finishings are used (different thicknesses, different windows… oh look! a chimney!), but the shape of our buildings is essentially always the same.

In the cold, mountainous north, where wind, rain and snow are frequent, heat must be retained within the buildings. There are numerous traditional ways in which this can be done: with a green roof, a layer of snow, or simply a thick layer of earth; solid wooden walls (tree trunks); or surrounding the building with a windbreak of tall, densely packed trees, such as pines, amongst other methods. Instead, we use bricks, and turn the heating on.

In hot, dry deserts, of which there are a few in our country, buildings must be kept cool. We could build something like at Ait Ben Hadu, or even tall, narrow U-shaped housing blocks facing southeast-south-west. Instead, we use the same bricks and the same colour as in the north, forcing our cooling units to work for most of the summer.

In temperate, slightly humid climates, buildings should be permanently covered by a roof (even if this is a hanging roof between floors) to avoid the sun heating up the building in the hot months when it is at its highest point in the sky, but which does allow it warmth from the sun when it is at a lower angle in the colder months. Instead, we use sunshades on the windows only, and have to install both heating and cooling systems, pay for both and emit CO2 throughout the year as if this had no cost.

In hot, humid climates streets must be narrow with white buildings reflecting the sun and providing shade for each other, thus cooling the city. Or public fountains and vegetation for cooling the air. But following our imposed standards, new buildings use bricks, and are separated by wide streets.

As an excuse, we claim that “we have always built like this”. Which is of course not true. We invest a lot of time in designing buildings, but we do this by using and reusing the same generic handbook with very few adjustments to take into account where we are building, and with a total disregard for the traditional knowledge which built up an area’s architectural heritage over many years.

It is indeed true that buildings designed to take the climate into account are more expensive that “standardised” buildings, but the difference between paying slightly more for your mortgage and having to foot the bill for heating or cooling your home year after year is not much. And the mortgage will eventually be paid off – in a short time, we hope –, whereas the climate is much more stubborn than the banks. Perhaps we should start adapting to it, don’t you think?

There are no comments yet