The conflict between humans and machines: perhaps we’re not ready for a revolution

14 of August of 2017

A world dominated by machines that enslave humans as a source of energy. A robotic system that acquires its own mind and decides to destroy all traces of the human race. A planet facing rebellion from machines no longer willing to put up with the humiliations they are subjected to by man. Science fiction has provided us with plenty of arguments to make us believe that the humans vs machines conflict will end badly. Is that the case? Is it time we destroyed our smartphones and defended a technology-free world?

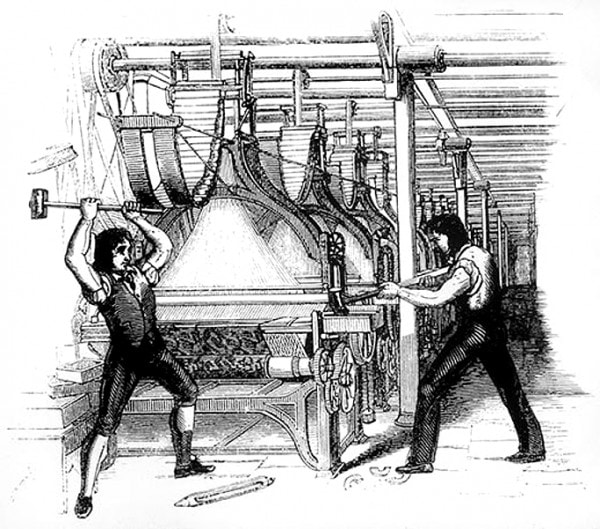

As the world becomes increasingly computerised, the debate around whether our society will be able to adapt to the revolution of machines grows accordingly. Some of the issues now being debated are new, but others have been around for some time. In England, towards the end of the 18th century when our industrial society started to emerge, groups of workers staged the first rebellions, furious that mechanical looms were robbing them of their jobs.

The key is in employment

The Luddite movement of 250 years ago was perhaps the most violent expression of man’s revolt against machines. But mechanical looms have not been the only innovation to challenge the labour market. Phone operators, essential for our communications sixty years ago, have disappeared. The milkman and the water carrier have long since made way for supermarkets and running water systems. And the town crier put down his bell in favour of other, less noisy, means of communication quite a few decades ago.

All of these individually are small changes on the slow road towards a world dominated by machines and artificial intelligence, with robots the most prominent expression of such change. Are we ready for this revolution? Or rather, have we ever been ready for any revolution?

A now famous study by Oxford University, published in 2013, points out that by about 2030, almost half of all jobs in the US will be performed by robots. “Our model predicts that most workers in transport and logistics occupations, the bulk of administrative workers, and labour in the production sectors are at risk,” claim authors Carl Frey and Michael Osborne.

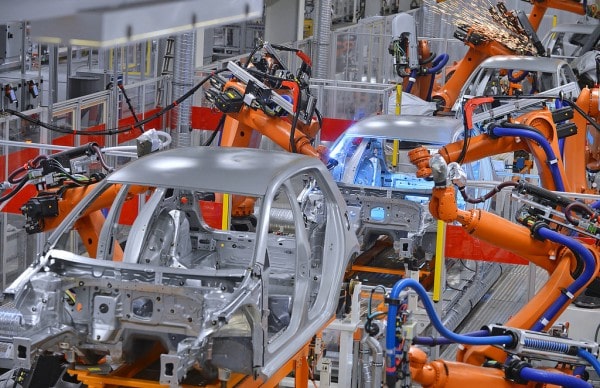

Without wanting to paint a Domesday scenario, these predictions seem altogether plausible. Particularly if we think of work as we know it, without considering types of future employment which we cannot imagine today. According to the >National Bureau of Economic Research, a public US organisation, the computerisation of factories has destroyed close to 700,000 jobs in the US since 1990.

Replacements are on the way

Robots are already replacing workers, and not acknowledging this would be akin to looking the other way. Again using the US as a reference, the latest report from the Robotic Industries Association claims that American enterprises acquired close to 10,000 robots in the first quarter of 2017, almost 28% up on the previous year. Moreover, the report points out that companies are increasingly turning to robots to boost productivity without having to invest in cheap (human) labour from developing countries.

The most pessimistic predictions on the impact of robots on employment are centred in China or Southeast Asia, where more than 70% of all jobs available today in these countries could disappear. This is because employment there is based on a model of poorly-qualified workers with low salaries producing consumer goods mainly for western markets.

“As machines learn not only to do more things, but to do them better, and certainly better than people and at a lower cost, it is simply absurd to think that the availability of the jobs we know today will increase. If we focus on employment as we know it today, forget it, there will be a lot less. However, we have to think of a world in which many people will be doing things that today are not considered jobs, but will be in the future,” explained Enrique Dans, professor of innovation at the IE Business School in a recent article published in the El País newspaper.

Dans favours social changes for adapting to the new reality where robots will be doing all the hard work, while humans will concentrate on the productive activities they enjoy most and are best at. “I see increasing evidence that we are moving towards a model where a fixed basic income will be a core element, and this is the case both where political thinking moves along the lines of a fairer redistribution of wealth, and amongst those with more liberal views.”

Humans vs machines – the real battle is about ethics

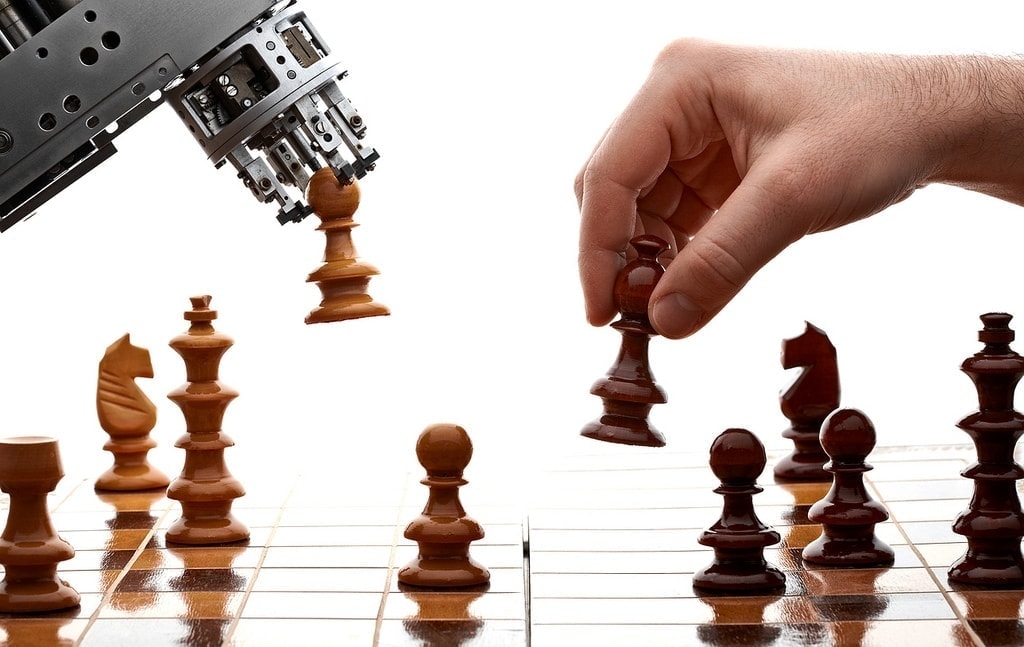

Going beyond Isaac Asimov’s laws of robotics and the specific impact of robots on our jobs, the debate is also centred on ethical and legal issues around a difficult question: can we really think of machines as our equals?

Well, it depends. “A machine will never be conscious of its actions. It may play a game of chess, but it won’t know that it’s playing, it won’t know what competing is, nor will it have the sense that it is competing with a person in order to win”, explains Ramón López de Mántaras, director of the CSIC’s Research Institute on Artificial Intelligence, in an article published by the EFE news agency. “There’s an element of motivation and intent which I doubt robots will ever achieve.”

Other experts, however, such as those working on the 2045 Initiative, believe that intelligence and robotics will evolve to such an extent that in about three decades from now we will be able to transfer our own human conscience to super-advanced machines which will overtake humans in all aspects, blurring the divide between man and robot.

The question regarding the motivation and intentions of artificial intelligence has many ethical nuances, particularly when debating the extent to which we will actually be able to trust it. How would a robot act in the event of having to decide between the lives of different groups of human beings? How would it determine what pain is, or the various levels of pain? Will it ever be possible to actually programme such aspects?

The future: apocalyptic, or rosy?

Too many questions, but not enough answers around. All we have are projections, some more pessimistic than others, and that unshakeable feeling, encouraged perhaps by Hollywood, that everything will be fine in the end.

Today, predictions regarding human-robot relations are led by two large groups, with much uncertainty in between. The most optimistic paints a happy future, where machines will take away all the hard work and us humans will simply live the life and be creative. The other, more pessimistic, group claims that the industrial revolution we are going through now is unprecedented and that we haven’t a clue what challenges lie ahead.

The optimists, such as the editors of the influential The Economist, suggest an overarching social compact to create a happier society, where workers will constantly change jobs and receive technological training, while the State provides a guaranteed basic income and social benefits underpinned by some sort of tax on robot workers.

Many experts from the more pessimistic group, whilst agreeing with this vision, believe it is unachievable. According to their view, inaction on the part of the State will lead to machines completely replacing humans in some sectors. In a world with fewer jobs, there will be neither the money nor the market confidence for consuming the goods produced. Their predictions are a massively computerised society with high rates of unemployment and deflation.

Our future will not be determined by Neo, nor by the replicants, nor by Terminator, not even by Wall-E. Once again, it seems that the ball is in our court. The technology is there and continues to evolve at a dizzying speed. It will all depend on whether we are able to adapt technology to our world. And trust that the way we do it will actually benefit us.

There are no comments yet