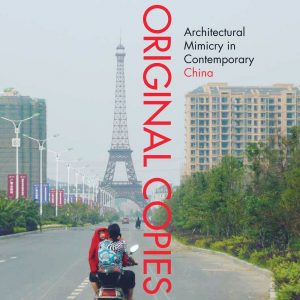

Inspiration, homage, and replica have always come up against each other in architecture throughout time. But that has, if anywhere, inevitably been in China. There, scattered throughout cities all over the country, can be found faithful recreations of the Eiffel Tower to scale, the London Bridge, the canals of Venice… Not to mention entire London neighborhoods, the White House in Washington, D.C., or the Great Wall of China itself.

Reporter Bianca Bosker explored this curious phenomenon in a book titled, Original Copies: Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China, listing current emblematic places, explaining how they came about, and most importantly – describing how that architecture affects those who live in those places. Because, far from being mere fake monuments and enclaves where you can take photos, the majority of those buildings and structures are perfectly functional, and people live and work in them. How does this peculiar atmosphere affect the population? What sort of urban planning do they entail? Why do these structures fascinate those who live there?

“Duplitecture”

Source: Bianca Bosker

In the fantastic podcast about architecture, 99% Invisible, they recover the term “duplitecture” to describe this phenomenon – which, as they explain, is not exactly new, nor is it unique to China: the San Franscisco Ferry Building, built in 1898, was inspired by the Giralda in Seville (from the 12th century), for example. The White House, where the president of the United States lives and works, took its design from the Leinster House, the Irish house of parliament. And even in Kolkata (India), there is a 30-meter tall replica of London’s Big Ben.

The case of China is paradigmatic because it combines architecture from all over the world. And because the feeling that these “planned cities” give could not be any stranger. In some ways, the photographs of them show completely artificial places, recreations that could be said not to have “a life of their own.” But many of them are not mere attractions for tourists but are considered to be places to live. There are those who say that they even slightly resemble the planned Soviet architecture of the second half of the 20th century.

The key, it seems, is that many of these places are recreated by Chinese architects and promoters simply to demonstrate that they can do it just as well as Westerners – something that is far from mere imitation out of some sort of interest (as happens with imitation brands, stores, or products) or from simple theme park homages. But sometimes, these “social experiments” have not turned out as well as hoped: it was expected that ten thousand people would live in the mini replica of Paris, with its characteristic buildings and boulevards, but there are barely one thousand occupants. And that is with a monumental, hundred-meter Eiffel Tower (a 1:3 scale to the original) towering over another vast recreation of the Champs-Élysées.

Symbols and cities

Thames Town in Songjian, Shangái | Source: Flickr | Author: Huai-Chun Hsu

Thames Town, in Songjian, is a replica of the most characteristic parts of the city of London – it even takes its name from the Thames River. With one million square meters of surface and room for some 10,000 inhabitants, there you can find its traditional church, the classic pubs, and even fish and chips stands. As it is relatively close to Shanghai (about 30 km from the city center, near the metro lines) housing sold rather quickly. The profile of its occupants? Primarily influential people that took single family spaces as second homes – which is why its streets suffer from the “ghost town” effect for a good part of the year.

In the port city of Dalian, there is a recreation of the canals of Venice, with its traditional bridges over several kilometers of canals. More than 400,000 square meters in all, encompassing an area where around one billion dollars were invested and that – as its inhabitants explain – lets those who cannot travel to Europe “get to know what the cities of the old continent are like.” In fact, the setting is rather peculiar, with gondoliers transporting people through the canals while they admire architectural replicas in various styles – a combination that turns out to be somewhat outlandish – around them.

New South China Mall. Arc de Triomphe

In Nanchang, there is even a replica of the Great Wall of China, something rather paradoxical since it is located right there in China. It measures just four kilometers (far from the original’s two thousand kilometers) and is built with modern, “aged” materials. Despite not being “the original,” thousands of people visit it every day – some even confusing it with the actual one. In the city of Huaxi, there is another replica that is also Chinese: Tiananmen Square. There is also the Sydney Opera House – and many other buildings from all over the world – scattered throughout the surroundings.

In 2012, even a replica of the Austrian town of Hallstatt was built in Guangdong. The inhabitants of the European Alpine village found out about the curious homage when construction was already well underway; their mayor stated that “perhaps it is beneficial to awaken interest among tourists that want to come to our town, and as cultural exchange.” Certainly, better to take it in good spirits.

More and more replicas

Wangjing SOHO | Source: Zaha Hadid

In a video from the architecture channel B1M, where they present a fantastic visual review of “the ten best replicas in China,” it is explained – again citing Bosker – that “for China, replicating many of those buildings and monuments is no display of hostility, nor is it an attempt to make perfect homages. It is more a show of power: the point is to make it understood that China can also create [or recreate] the best architecture that the world has offered throughout all time.” Will this give way to copy-paste architecture in the future? Is everything fair game when it comes to being inspired, imitating, or recycling the work of others?

An especially peculiar case – now entering the realm of modern architecture – is that of Meiquan 22nd Century. This is about a group of buildings with the same appearance as the Wanging SOHO and Galaxy SOHO complexes from the Zaha Hadid studio. With their characteristic, smooth forms and curves, they were presented to the public in 2011 for their construction to be completed around 2014. But in 2012, Meiquan 22nd Century appeared in the sector’s news and fairs, with an unmistakably similar appearance, and with the ironic fact that it would be completed before Zaha Hadid’s. Accusations went flying; lawsuits were even discussed, and it was said that the imitators were based on the 3D renderings of the original design. Even the Chinese Office of Intellectual Property – typically rather lax when it came to this regulation – had to intervene to study the differences: one had three towers, the other two. And it is well-known that it is difficult for two identical buildings to exist in the world, given their location, the terrain, sunlight, the environment, etcetera. The developers of Meiquan 22nd Century claimed that “copying was not the intention, just surpassing.” In the end, 22nd Century was delayed, and Wanging SOHO could finish beforehand.

Meiquan 22nd Century | Source: SouFun

Come what may, in some sense visiting these Chinese buildings and infrastructure also means revisiting other carefully cloned parts of the world in an attempt to demonstrate that anything is possible in China – whether that is the London Bridge, the neighborhoods from the French City of Lights, or the United States Capitol. All a show of power.

There are no comments yet