Every year, Madrilenians spend an average of 42 hours in traffic jams. And that’s even far from the worst city for jams on the INRIX 2017 Global Traffic Scorecard. A Bogotan wastes 75 hours every 12 months. A Londoner, 74. And those who live in Los Angeles spend the most time in traffic jams out of anywhere in the world at 102. Traffic slow-downs drain our time and quality of life, and they contribute to urban pollution, everywhere from big cities to smaller towns.

The fact that the roads and highways we travel on are full is the main cause of traffic jams. That is, if roadways don’t have the capacity to absorb all the vehicular traffic, jams happen. However, the problem is much more complex than that. Drivers’ habits and management of the highways themselves also have an impact. Sometimes, bad traffic even seems to happen for no apparent reason. These are some of the less obvious reasons that may be behind a traffic jam.

A technical definition of “traffic jam”

The friction between travelling vehicles is the fundamental cause of traffic congestion. According to the ECLAC, the United Nation’s Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, “up to a certain level of traffic, vehicles can move fairly freely at a speed constrained only by speed limits, the frequency of junctions, etc. When volumes are higher, however, each additional vehicle hinders the movement of the rest, meaning that congestion begins.”

The consequences of traffic jams are clear to anyone that has ever been stuck in one. The time lost and the resulting opportunity cost (being in a traffic jam isn’t a productive activity), the delays and impossibility of predicting travel time and cost, the fuel wasted and added pollution, the wear on vehicles cause by frequent acceleration and braking, and the drivers’ and passengers’ frustration are just a few.

The causes behind this friction between vehicles range from accidents to construction, weather conditions to even the path of the road itself. Nonetheless, as Spain’s Directorate General of Traffic indicates, “for a gigantic traffic jam to happen, there doesn’t have to be an accident, a winding road, or a lot of trucks.”

Braess’s paradox

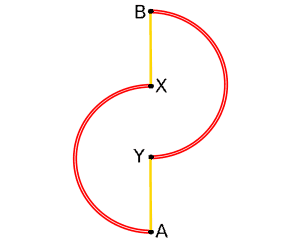

The behavior of traffic flow has a lot to do with how drivers react to unforeseen situations. And adding more lanes to a road doesn’t necessarily alleviate traffic. This is what is known as Braess’s paradox, described by German mathematician Dietrich Braess in 1968. With a simple experiment (see the figure above), Braess showed that by adding more lanes or space to a traffic network, users’ performance may end up being even worse.

Let’s image that the yellow lines are conventional roadways with one lane in each direction. By progressively increasing traffic over time, there are continually more traffic jams. So the decision is made to build a new roadway, a high-capacity highway (represented by the red lines). The effect that may be produced is that all the drivers choose the new roadway because it theoretically reduces travel time. This saturates the new infrastructure, and the problem is back to where it started.

Source: Unsplash | Author: Denys Nevozhai

The accordion effect

Just as in the previous case, mathematics and physics provide an answer about traffic jams that seem to happen for no apparent reason. In 2008, a group of scientists from the University of Nagoya in Japan showed the impact of the accordion effect on traffic. In their experiment, described in a paper published in the New Journal of Physics, they placed 22 cars on a circular track 230 meters long with only one lane.

They all started off by travelling at the same constant speed. Suddenly, for no apparent reason, one of the vehicles slowed down. In the real world, this deceleration may be caused by a distraction, an unexpected situation, or poor road conditions, among other things. The cars behind the decelerating vehicle started braking. The distance between them started to close until one of them stopped completely. From that point on, the rest of them found themselves obliged to stop, and there we have a traffic jam.

The effect also holds in the opposite case, as the DGT indicates. If, for example, there are 2,000 cars stopped in a single-file line, when the first one starts to move, the line of vehicles stretches out like an accordion. The second car starts a second later, the third two seconds later, and so on to the last one, which starts moving about half an hour later.

The rubbernecker effect and the zipper effect

Why does a vehicle slow down with no warning and for no apparent reason? According to an RACC study (Catalonia’s automobile club), looking for parking in urban centers, a cyclist or pedestrian, and roadwork are some of the reasons why drivers hit the brake. Many others fall under what has been described as the rubbernecker effect.

When something gets the driver’s attention, they tend to slow down or even brake to stop the car. This could be a broken-down car, the scene of an accident, or even an attention-getting billboard. According to the DGT, this rubbernecker effect causes traffic jams and may even cause accidents.

Ante un estrechamiento del carril, si tod@s aplican el efecto #cremallera, la fluidez del tráfico mejora. ?RT#paciencia #BienvenidoAgosto pic.twitter.com/XIBKJZJ4HT

— Policía de Madrid (@policiademadrid) 1 de agosto de 2017

In response to the rubbernecker effect (and a possible solution for the accordion effect), drivers also have the power to reduce traffic jams with a practice known as the zipper effect. If one of the lanes is blocked by an accident, construction, or a breakdown, the best solution is to alternate right-of-way between vehicles in both lanes. So instead of accelerating to not let the car that is stopped in or trying to “cut” into the moving lane, right-of-way should alternate between vehicles in both lanes.

Even though it’s true that the road’s capacity is related to traffic congestion, there are reasons that directly depend on drivers. Good trip planning (avoiding rush hour, if possible), using proper signaling in case of an accident, not letting oneself get carried away rubbernecking, and giving priority to the efficiency of traffic as a whole may contribute to improving traffic flow on the roads.

There are no comments yet