Closing the gap between the citizen’s outcomes and the ‘expert’s’ vision is key to unlocking innovation within local government

13 of February of 2019

Infrastructure planning and development has traditionally been an exceptionally paternalistic affair, with experts defining and executing their vision, alongside strict commercial instruction from governing authorities. When considering the workings of a future ‘smart city’, this top down approach renders us with a rather Bauhaus vision of intelligent sensors and transport arteries, relaying a constant stream of data back to a central control hub. In this techno-dystopia, our controllers would usher us through their ecosystem based on principles of efficiency and safety, with no distribution of knowledge and no agency to affect the system from the outside. Because this top down approach is not agile towards the changing demands of the citizens it serves, the user experience suffers. We often define a dystopian future by its lack of citizen agency, but the reality is, that almost all our infrastructure is guilty of either an overzealous technocratic approach to organisation, or a myopic prioritisation of commercial gain.

In the opposing corner, is the city digitalised from the bottom up, with its innovation driven by the citizen’s needs; in this future, smart technology is not based around billion-dollar investments by central organisations, but a distributed network of participating individuals and technological elements both transmitting and receiving information with their own autonomy. With George Orwell’s 1984 as our moral backstop we have made remarkable progress towards a state of distributed agency , with apps and social networks allowing us to navigate, edit and influence the cities we live in, telling authorities what we need rather than waiting to be told. It’s only relatively recently that the development of our cities and the vision for their future has begun to swing towards citizen centricity within the planning stage of infrastructure, with citizen engagement traditionally a retrospective evaluation, if done at all. Rapid maturation in digital technology is bringing citizens closer to their surroundings, creating choice and dispersing agency across communities. Despite digitalisation now being a key driving force for urban growth, this was not always the case.

Boston city centre

During much of the 20th century, there was a logical expectation that the de-centralising characteristics of technologies such as rapid transport and the internet, would lead to the explosion of sub-urban communities and garden cities, which we saw during the latter part of the 20th century. However, city living has seen a renaissance in the 21st century. If the rapid urbanisation of see today continues, over 70 percent of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050 (UN DESA, 2018). Urbanisation is at its most potent in developing countries, where the standard of living can dramatically increase in towns and cities. Cities provide the perfect platform for a fast-paced populace to flourish and can offer levels of choice and diversity in consumption that are only sustainable within the dense environment a city provides.

The expansion and digitisation of cities has shined a new light on the competing forces of top-down technological and expert vision with bottom-up citizen driven outcomes. Western cities are littered with examples of form-driven technocratic city planning;

City plazas designed throughout the late 20th century are the product of an architectural vision rather than a facilitator of outcomes for the citizens intended to use it. Sharp angles, water features and wide-open spaces may be visually striking and cheap to maintain, but how does a citizen use them? Or dense high-rise accommodation, which is designed and constructed with the ambition of supporting the maximum number of residents per square metre, with little appreciation of the lived experience of the user. Innovation in infrastructure services and construction has traditionally centred around asset lifecycle cost, however there are ‘green shoots’ suggesting we are now seeing a broader set of outcomes being considered.

High-Line in Manhattan

The High-Line in Manhattan is an example where a city and a community have come together to not only save and re-purpose aging infrastructure, but achieve an entirely different set of outcomes from which the original infrastructure was intended. Seen as an eye-sore and an impediment to further residential development, the dis-used rail line in New-York was due for demolition in the early 2000s. However, a community group, run entirely by citizens, emerged as a force for its preservation. This group was able to evidence that should the railway be turned into a public park, the economic, social and cultural value generated would far outweigh its cost to demolish. This group was successful in ensuring the High-Line’s preservation, and eventually evolved to fund, manage and maintain the asset. The park achieved planning feasibility based on 40,000 visitors a year, however the outcome has been that it is attracting 5 million visitors a year, making it the second most visited cultural attraction in New York with an estimated $2.2 billion impact on new economic activity. Increased tax revenue from the High Line neighbourhood will bring in almost $1 billion.

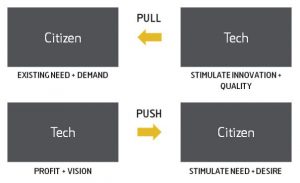

Scenario 1 and 2

The concept of competing forces of ‘expert’ (or in the case of smart cities – technologist) and ‘citizen’, came from a workshop with our ‘Leaders in Urban Excellence’ group in the UK. Our members are passionate about bringing their own vision in line with that of their community and see this lack of concordance as a key blocker to successful innovation scale of the local network. In an age of increasing technological maturity, tech is pushed towards the consumer (Scenario 2), an example being in the luxury consumer tech market where almost all existing demand/need has been met already.

In infrastructure procurement, this dynamic translates to an environment where clients are faced with a market of products, rather than solutions. Investment in new, technologically-enhanced physical assets, without use-case or outcome identification, hinders successful innovation because the value of the intervention can never truly be understood. When it comes to digitalisation, we must identify the value chain of the intervention, with the outcomes of the citizen driving our decision making (Scenario 1). Involving the citizen and placing their needs at the heart of the planning process is key to unlocking digital innovation within local government. As evidenced by the New York High Line, thinking innovatively around outcomes will allow us to not only procure better, but realise the potential of our existing fixed assets facilitating a closer relationship between citizens and experts.

There are no comments yet