Water Infrastructure to Combat el Niño

Under the business responsibility program Social Infrastructure, and along with the NGO Ayuda en Acción, five Ferrovial employees visited the community of Cura Mori to set up the basis for access to potable water.

05 of June of 2019

It’s only been two years since the Peruvian government declared a state of emergency across the country. Floods from the El Niño phenomenon left catastrophic figures in its wake: 1.4 million Peruvians affected, more than 160 deaths, and over 280 thousand victims. These numbers highlight the raw force of nature. The effects of climate change threatened to return in 2019.

From January to March of 2017, it devastated the Latin American country. El Niño brought torrential rains throughout Peru, which especially punished the northern part of the country. Specifically Piura, the region most affected by this phenomenon. Many of the residents of the city told us, as if it were yesterday, how on March 27 the river rose over the dams and devastated the region. The river’s overflow exceeded 3,000 cubic meters of water per second.

As residents from this northern area told us, the El Niño phenomenon happens when seawater exceeds 25°C for long periods of time. During those days, the primary roadway infrastructure collapsed, the streets were rivers of mud, and many citizens had to seek refuge in improvised shelters on the Pan-American highway. This was the case for residents in the town of Cura Mori, a place that the government of Peru declared to be at unmitigable risk.

For this reason, Ferrovial, along with Ayuda en Acción decided to launch a project to help improve the lives of the more than 1,000 residents from the districts of Chato Chico and Chato Grande, belonging to the town of Cura Mori. In this area, the river’s overflow caused flooding in both communities, limiting access to public services and destroying the water supply systems. During our visits to the communities, we were able to see how families currently have access to potable water for about two hours every two or three days; many of them do not have access to water; and a majority do not have bathrooms in their homes or any other sort of sanitation. Cura Mori is an area with some of the highest poverty indexes in northern Peru.

To kick off this project, we chose different profiles from the company to promote the study. Through the selection and evaluation phase, a team of volunteers composed of experts in different subjects was formed: Miguel Sanz and Anna Grassot, Civil Engineers specializing in structures and hydraulic construction; Lidia Cazorla, specialist in Topography; Jaime Fagoaga, expert in Communication, and Inés Cruces, head of the Health and Wellness field.

Drinking water channels, eco-latrines, and awareness

- The project involves improving the quality of life for the community through access to water supply systems. The performance fields include:

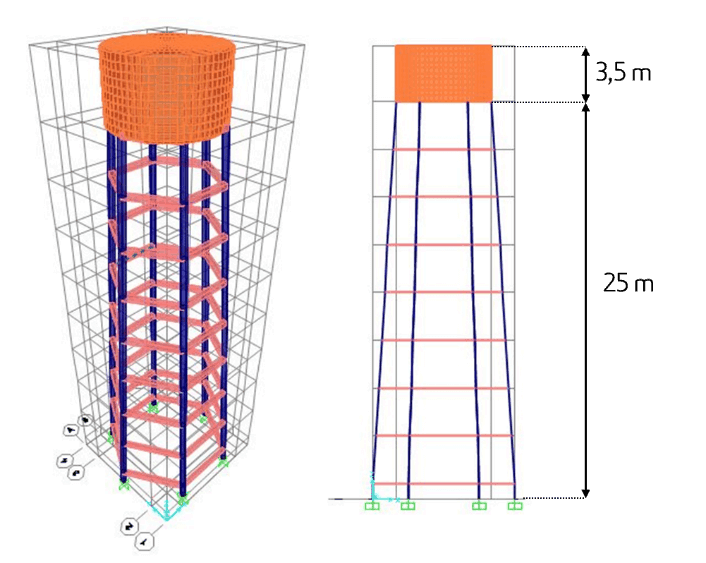

- Demolishing the existing tank and building of an elevated tank that provides water with the necessary water flow for 24 hours a day, as well as improvements to the domestic supply to guarantee access to potable water. The current elevated tank has a capacity of 80 m3 and is 25 meters tall, and it has fallen into disuse and is in danger of leaking.

- Improving the sanitation infrastructure by installing 84 eco-latrines and providing maintenance kits for the latrines. That will enable improving

- Raising awareness among the population about healthy habits through workshops and training in water management systems.

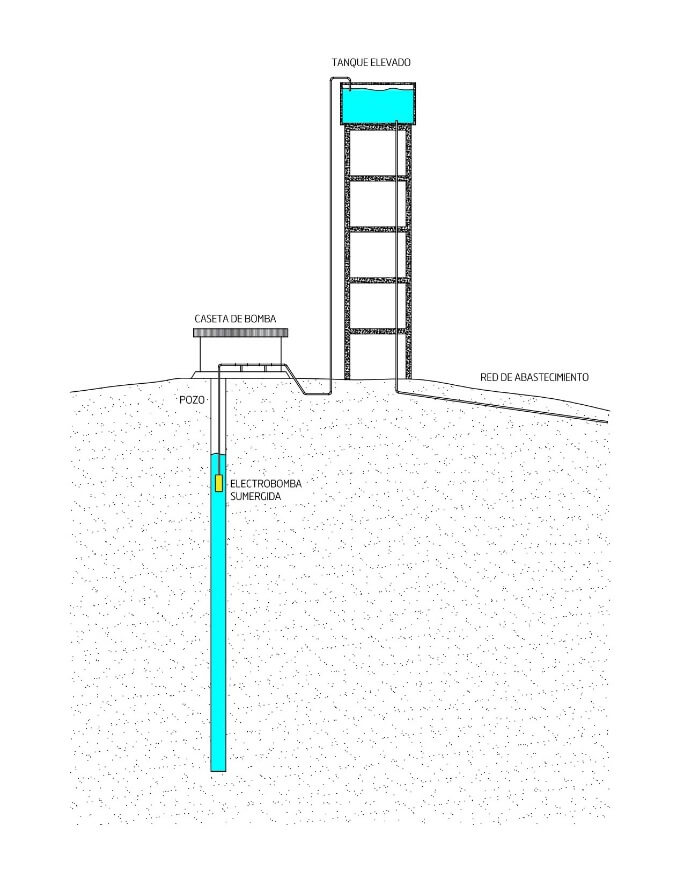

Graphics on how the water grid works

Graph of the height of the tank

Five volunteers and one environmental challenge

After several training, informational, and contextual sessions about the country, the team of five volunteers simply wanted to pack our bags and get to the area as soon as possible. The day finally came, and one Sunday at the beginning of March, we landed in Lima. After a few days of meetings with the Ayuda en Acción team, we traveled about 1,000 kilometers to the north of the country, to Piura. This arid city, surrounded by coast and desert, became our headquarters.

In the starting phase, our day to day work involved the project’s initial study. Site visits, infrastructure studies, pipelines, water tank, topographical measurements, as well as holding interviews and meetings with the residents in the communities and heads of infrastructure (the city council, the regional government’s infrastructure area…). The questions didn’t leave time for silence, as time was limited. Our agreement was clear: finishing a project proposal in a period of two weeks.

After this first part, there was a second phase more focused on implementing all the information gathered at the sites. The art of mathematical calculations, measurements, developing plans for security, and raising awareness interlaced in preparing a report to launch the project. This document was presented to the city of Cura Mori to come to agreements on priorities and raise awareness of the importance of the potable water supply in this region.

Climate, terrain, and available resources

As we were used to working in environments with all the necessary resources, the experience of developing a civil engineering project in Cura Mori opened our eyes and made us face a different reality. Among the challenges we faced were:

- Climate conditions: one of the biggest challenges we encountered was working in totally different conditions. The area’s climate is extremely dry with temperatures around 40 degrees. The terrain is desert sand, with little consistency. As a flood zone, we had to make sure that any interventions we made would hold up over time.

- Relating to the local population: another aspect to highlight is the relationship with the communities. People who have no idea who you are, who have been through very tough situations, and who are living in extreme situations, with no reason to open their doors to us and tell us all the details of what their day-to-day life is like in terms of water. This was very gratifying for us.

- The means available: another challenge was the means we had when it came to taking measurements or seeing the actual status of parts of the existing water supply network. The resources were scarce, and the use of technology or meters was non-existent.

- Back to analog: access to information records on construction that had taken place previously was another stumbling block. In Piura, the local administrations didn’t have a digital record of the documentation. We got most of the information from the community itself, through testimonials or on paper. This helped us understand that you can’t always have everything neatly handed to you, but sometimes hypotheses also work.

- Safety first: to tackle the water tank’s demolition, we had to go back in time, getting out of our comfort zone and looking for resources that third parties could provide. Even so, we managed to develop a safety plan to bring down the tank safely for those doing the work as well as the surrounding infrastructure and homes.

2020: potable water 24 hours a day

Thanks to this project, it is estimated that by the start of 2020, the 1,000 residents of Cura Mori will have new connections and infrastructure that will supply potable water 24 hours a day. Families will have 168 water meters to pay according to how much water they actually use; in addition, homes will have 84 latrines. We hope that within a year, these mere figures will indeed become real improvements to their quality of life. For us, we got so much more from this project than what we gave. But one thing is certain: we’ve had one of the best work experiences of our lives.

There are no comments yet