Tactile Paving, a Useful Invention That Is Part of the Silent Language of Cities

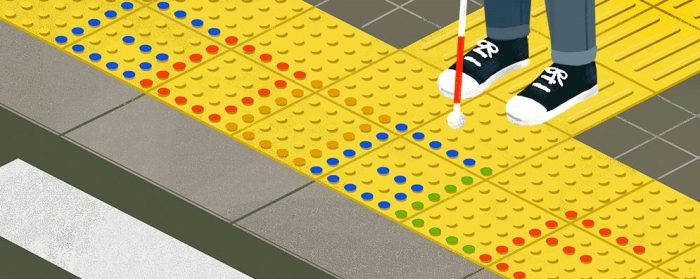

One part of the city that goes unnoticed by many of its residents but that is all around us on sidewalks and in public spaces is tactile paving. These small, raised bumps are typically square and painted yellow, are set off by dots or stripes, and are located in strategic zones: intersections, curbs, lanes, and metro stations. They go by many names, but all have the same creator: Seiichi Miyake, a Japanese man who had this wonderful idea around 1965.

22 of July of 2019

An invention born of necessity

Miyake’s invention goes by many names all over the world: Tenji blocks, tactile blocks, Japanese Braille – though the technical name for them is tactile paving. It is useful for blind individuals or those with vision problems in getting around on the street and in public spaces. It is an accessibility feature that can easily be detected with a cane, with feet, or even with the help of trained guide dogs when installed on pavement.

As the story goes, Miyake thought up this invention to help a friend who was beginning to have vision problems. Around 1965, he invested his own money in manufacturing these tactile blocks, which were raised to indicate two different situations: “caution” (dots) and “it’s safe to continue” (parallel bars).

The city of Okayama was the first to install this invention in 1967, doing so with bright yellow blocks so that individuals with vision problems could make them out, as well. In the 70s, when they proved to be especially safe in stations and on platforms, Japanese National Railways began using them and made them obligatory. In 1985, they were in use all over the country and then the world, where they have been a regular, necessary part of “urban language” for some time now.

A theme and variations on it

Photo: L3 (CC) Carlos Alvz. Cor. @ Flickr; Celebrating Seiichi Miyake / Google

Tactile paving hasn’t changed much over time, as the basic concepts are still the same. The bricks sometimes change in size, but they’re usually square or rectangular. The main thing is that they offer a change in contrast and texture. They are manufactured in cement, stone, rubber, or sometimes as a high-resistance adhesive strip placed on conventional pavement. There are also polyethylene and metal versions (especially for interiors) and variants in colors like yellow, pipeclay, and red tile. It’s normal for this paving to be installed in metro and train stations, at bus stops, hospitals, shopping centers, and other public spaces.

Since tactile paving makes surfaces irregular, it can be a little uncomfortable for those who cross it in wheelchairs, strollers, or with walking sticks. It is therefore used only when strictly necessary, not on all pavement. Its use always follows a few rules: the round blocks mark the edge of sidewalks and crosswalks; the bars appear where there are no obstacles of any sort. They are not normally installed along walls, though they are where there is any feature that might be an obstacle.

For some specific projects at ADIF stations, there are more detailed accessibility regulations that specify what the blocks, safety strips, and yellow stripes on the pavement and at the edge of the platforms, stairs, and doors must be like to guide all travelers with visual impairment.

Tactile paving is already something so common and woven into city life that Google even paid tribute to Seiichi Miyake with one of its doodles to mark the anniversary of the first installation of his invention.

There are no comments yet