Extreme Engineering: Building a Solar Thermal Plant in the Driest Place in the World, the Atacama Desert

29 of May of 2020

During some trip to a remote, exotic place akin to paradise, you’ve probably seen unique construction and considered how difficult they must be.

What do you think of the Atacama Desert in Chile? Surely, we’ve all heard of it because it is the “driest place in the world” (0.5 cubic millimeters was the average precipitation between 1964 and 2001).

The Atacama Desert is located in northern Chile, and it is known for being comparable to Mars. As such, several scenes of the Martian landscape have been filmed there, one of the best known being the television series Space Odyssey: Voyage to the Planets. Its unusual features have led NASA to use it as a testing ground for future expeditions.

Another one of the desert’s main features is that it has abundant natural resources. Its soils are home to the largest reserve of copper and non-metallic minerals on the planet, thus the high concentration of mines in the region.

On the other hand, it is the location on the planet that receives the highest levels of sunlight, a yearly average of four thousand hours of sun.

With these characteristics, we can say it as a unique place to build something, don’t you think?

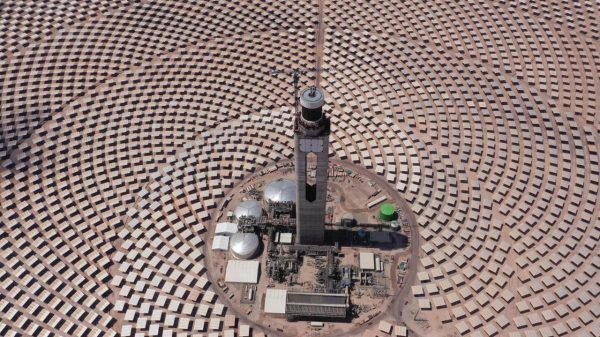

This is how the Cerro Dominador Solar Thermal Plant is located in the commune of María Elena, and it has a storage capacity of 17.5 hours and a production of 110 MW. It is known for being the largest plant in South America.

At the epicenter of the plant is the tower that houses the receiver at 220 meters high, thus reaching a total height of 250 meters. It is surrounded by 10,600 heliostats that follow the sun’s path with movement on two axes. This tower is the second tallest structure in Chile, following the Costanera Center in Santiago de Chile. This complex will prevent the emission of 870,000 T per year of CO2 by supplying clean energy.

Because of these extreme conditions, Edytesa, a Ferrovial company specializing in unique construction endeavors, was entrusted with this project. And I assure you, this project is quite unique.

What are slipforms?

Slipforms are a construction technique that facilitates the execution of certain structures. This technique consists of a rigid formwork, which moves vertically at a rate of 5 to 20 cm/h while hardening the concrete poured into layers in the slipform, and it is lifted by a hydraulic jack system.

Among its other singular features, this system offers a constant 24-hour working rhythm, so the organization must be done down to the millimeter.

My experience as an engineer in the Atacama Desert, Chile

After carrying out the project in Spain and sending some of the necessary material, it was time to pack our bags to embark on a new adventure.

Landings don’t tend to go smoothly, and this was no exception. As soon as we arrived, we were met with the first administrative and bureaucratic complications. It took several days to sort things out until we finally got the green light on the project.

During construction, the entire team stayed in the city of Calama, a city famous in Chile for being the city of the three Ps in Spanish – in English, Dust, Dogs, and the third word, also beginning with P in English, not for polite company. It isn’t looked upon kindly among Chileans themselves. Lodging was about an hour from the worksite, and part of the way was through the desert. It was our daily Paris – Dakar.

As I mentioned previously, some of the materials for the project were sent from Spain. Others were manufactured in the Chilean workshops, specifically, the heaviest, bulkiest parts of which the slipform was composed.

Well, once we received the material, we got to work. The slipform’s assembly was rethought, with resulting nerves and hastiness at first, but in the end, the work, along with the effort of the team’s first advance, came out ahead.

After a lot of coordination with the project, the workshop, the workers… D-day finally rolled around, which was none other than the beginning of the slipform. That day was full of nerves and preoccupation as many eyes were on us. During this sort of operation, I can assure you that many factors come into play, but it was all worth it because the button that started the slipform in the hydraulic power plant was a success. We didn’t expect anything less.

As I said, the Atacama desert is known for being the driest in the world. Even so, it is curious that I think I will be one of the few people who has seen rainfall twice in the desert. For outside construction projects, rain is usually an inconvenience. I can assure you that this challenge multiplies in the desert, bringing an even greater need for management and coordination.

Another of the “curious” episodes we experienced were the earthquakes. The first one I went through happened during a project meeting; at first, I thought it was a steamroller going by, but as soon as I saw the local staff’s expressions change, I realized that this was not normal, so we got out of there as fast as we could.

Despite it all, we kept working and sliding little by little, fighting against concrete, auxiliary resources, problems with material deliveries, setting rebar, the soccer final at the Copa América, the sun, the temperature change from day to night, and different problems that came up with the project that we had to address in the best possible way so as not compromise our pace.

Even with all of these difficulties, both the project and the team were happy with the hard work we did. Until the day everything came to a halt. The standstill was the result of a strike, and it caused the pace of the project to slow down. After several weeks, we were finally able to continue our hard work, which lasted a few more weeks.

Fortunately, in some cases, as the song says, everything comes to an end, as it did when we pushed the last button, the last rebar was set, and the last bucket of concrete was poured. At that moment, we were all hugging and joyous, suddenly forgetting the hard moments and, of course, feeling so proud to have worked on the project.

There are no comments yet