When European colonizers started to ship maize from America to Europe, they noted that it adapted to the temperate, humid climate of Galicia well. The region already had buildings raised off of the ground that allowed them to keep grain crops and other food safe from inclement weather and animals. These were granaries.

Several hundred kilometers away in the peninsula’s interior, there were different needs. A different climate and crops brought about the construction of silos, dovecotes, and windmills over the years. For the most part, these structures are no longer used as they were but are still standing.

We’re going to review several traditional structures from different parts of Spain that were necessary at other times and are now part of these region’s histories and landscapes.

What is an Hórreo?

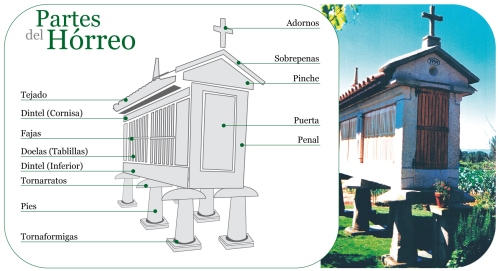

These typical spanish granaries are for storing, drying, and preserving food. In Galicia, Asturias, and northern Portugal, where they are more common, this requires good insulation, ventilation, and moisture protection.

These are storage chambers made of stone or wood, raised off of the ground with supports. Though their shape and materials depend partially on the area and the type of grain to be stored, they usually have a few common characteristics. There are, for example, what are called tornarrates in Galicia: usually convex surfaces that separate the chamber from the columns and other supports, and which prevented rodents from getting to the food. Similarly, there are usually tornaformigas at the feet. These are small pits filled with water that keep ants from climbing into the chambers.

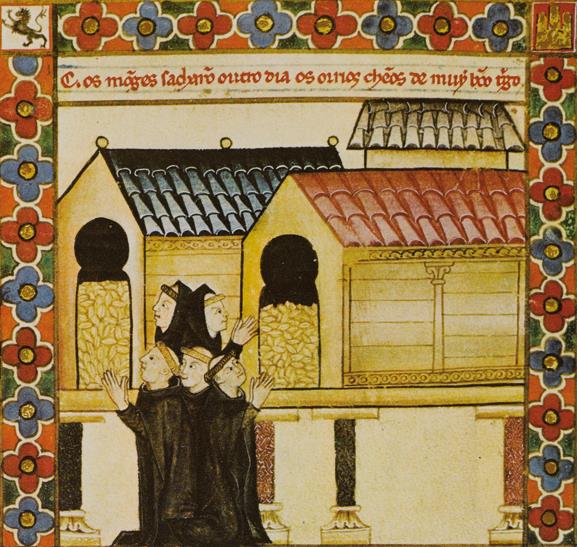

The granaries are thought to come from buildings once used in Celtic villages, even though the first visual representation that remains is in the pages of the Cantigas de Santa María, attributed to Alfonso X the Wise and dated to the 13th century. This evidence suggests that these buildings were in use long before corn was introduced to Europe.

However, once it was introduced, many granaries were built specifically to store this food. Some are still in use today.

The granaries of the peninsular northwest have many similarities with other raised granaries that can be found in different countries in Europe and other continents, such as Scandinavia, Switzerland, and Japan.

What is a Silo?

The use of silos, underground holes where grain and other materials were stored, dates back to ancient Greece. However, throughout history, many silos were no longer underground and started to rise as large towers.

In Spain, most of the large silos were built during the Francoist dictatorship. They are mostly found in the regions of Aragon, Castilla y León, Extremadura, and Andalusia, and they are so iconic that many know them as the cathedrals of the countryside. During the dictatorship, more than 600 silos were built, but the grain warehouses fell into disuse in the last few decades of the 20th century.

Their main purpose was none other than to store grain and other foods like olives, though some had other, more specific purposes. The structures were also used to facilitate introducing, issuing, and sorting the material. This sometimes involved the use of machinery, given their size: some silos can measure up to 30 meters high and can store tons of grain.

Generally, this machinery was based on elevators and systems that allowed the material to be divided into different cells.

Currently, this maintenance is complicated and expensive. Some of these buildings have been remodeled as museums, theaters, libraries, and even one student residence, to name just a few.

What are the dovecotes?

Another structure that is very characteristic of Castilla y León, especially in the Tierra de Campos region, is the dovecote. These were built to raise pigeons and chicks for their commercial use.

Dovecotes were built with materials like mud and adobe, and they managed to maintain a cool temperature while protecting from water, cold, and humidity. Inside were rows of small alcoves for pigeons to nest.

Over the centuries, pigeons were bred to either be sold as food or become carrier pigeons. In addition, pigeon droppings, called palomina in Spanish, were used to fertilize crop fields. However, raising pigeons declined in the second half of the 20th century.

Today, many of the dovecotes that dot Castilla y León have fallen into disuse and poor conditions, though they remain a cornerstone of its landscape.

What is a Mill and what type of them are there?

It is estimated that the first mills appeared as far back as the expansion of agriculture. For centuries, humans have used energy to power different grinding mechanisms.

Generally, the most basic mills consist of one fixed circular stone and one that moves. The latter rotates on the former, driven by energy from wind, water, people, or animals (forming windmills, watermills, mills powered by working animals, and so on). Over the centuries, mills were perfected so that it was possible to grind more material and achieve higher quality results with less effort.

Around the world, numerous regions have mills of different types from different eras. In Spain, the windmills of Castilla la Mancha are especially recognizable.

These mills, which were immortalized in the pages of ‘Don Quixote de la Mancha,’ are usually based on a cylindrical stone structure that a separate upper part rests on. This may be rotated to turn the blades depending on the wind direction.

Inside, a system of gears and stones make grinding – usually wheat – possible. From the 16th century on, mills were a vital part of the economy in some regions of Spain, such as La Mancha, up until the mid-20th century when they ceased grinding.

Today, the landscape of La Mancha combines these mills with current models, which generate wind electricity. Above all, they are visited by lovers of history and literature.

There are no comments yet