An Impossible Project Between the City of Tiles and the Hillsides of Wine

11 of January of 2021

As the 19th century drew to a close, the banks of the Duero River saw busy businessmen and workers coming and going near its mouth to the Atlantic. Porto rivaled Lisbon in leading Portugal as the standard-bearer of liberal values with strong, organized industry. The time had come to equip the city with new buildings and infrastructure at the height of its importance.

Two of those works survive to this day. They’re connected as part of a project that was considered impossible for many years. One is the Porto-São Bento Station, whose atrium is lined with over 20,000 tiles. Though it has been in operation since 1896, it wasn’t finished and inaugurated until 1916, when its pastel mosaics, a symbol of Portuguese Art Nouveau, were complete.

The other project was the Dos Guindais Funicular, a light rail line that climbs over the hill of tiles. On the other side of the river, it overlooks Vila Nova de Gaia, the home of the fortified wine that has made the city famous. The cable-car was short-lived. It closed only two years after its inauguration in 1891 following a serious accident. However, the project was eventually revived and reopened to the public in 2004.

Today, the tiled station and the cable-car line between the Ribera del Duero and Praça da Batalha are part of a larger network that’s partially underground. Once postponed for decades, this infrastructure has become the backbone of the metropolitan area of the city in a short time. With its 70 kilometers of lines and 82 stations, the Porto metro has more than 60 million passengers each year.

Ready for some soccer

A Porto metro car as it travels through the city over the Luis I bridge. Wikimedia Commons/Barcex

A Porto metro car as it travels through the city over the Luis I bridge. Wikimedia Commons/Barcex

The history of cities is framed by the development of their infrastructures. When Porto mayor Fernando Gomes gave the green light to the metro project in the early 1990s, many thought it couldn’t be done. It wasn’t the first time there had been talk of connecting neighborhoods with the sort of rail infrastructure that could be found in major cities around the world (including the capital, Lisbon, since 1959).

Even so, little by little, administrative procedures and financing were completed. On March 15, 1999, when Gomes had barely been in office for six months, construction officially began. Line A, between the Matosinhos city hall and the Trindade station in the heart of Porto, was opened in December 2002. It had 11.8 kilometers of tracks above ground (except for a 500-meter tunnel at Lapa) and 18 stations.

This first line was expanded in the following two years to connect the city with the new Dragao stadium, one of the venues for Euro 2004. This work on extending the line with five new underground stations was done just in time for the soccer tournament, which drew nearly one million visitors to Portugal. With that, Line A was complete.

From then on, there was one extension after another. In 2005, the first section of line B opened. Today, it runs through the metropolitan area from east to west. This line is built along part of an old railway route that linked Póvoa de Varzim with Porto in the 19th century. Then came line C, which connected with Maia to the north, and line D, all in the same year.

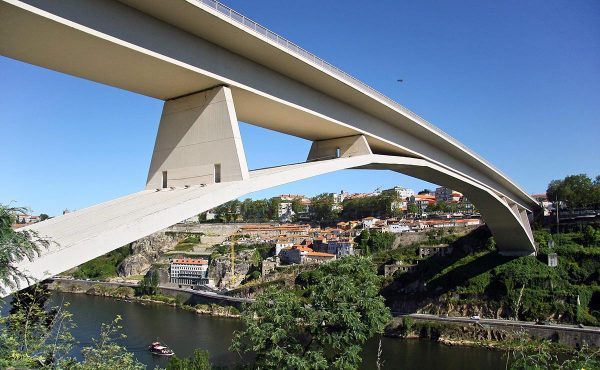

Line D is the most-used today (not counting the common artery consisting of several lines in the city center). It connects the university campus and the São Bento hospital with Vila Nova de Gaia, as well as the tile station, the railway junction in the heart of the city. The line doesn’t cross the Duero underground; it soars over the river via the Infante Dom Henrique bridge, a lone arch made of reinforced concrete spanning 280 meters.

Almost all of the connections continued expanding, and lines E (to Francisco Sá Carneiro airport) and F were added. D was last extended through Vila Nova de Gaia in 2011 to connect to the Santo Ovídio station, the first underground station in the city. The next stretch of metro line will start there, and Ferrovial Construction will be in charge of it.

The Infante Dom Henrique bridge over the Douro River as it passes through Porto. | Wikimedia Commons/Vitor Oliveira

The Infante Dom Henrique bridge over the Douro River as it passes through Porto. | Wikimedia Commons/Vitor Oliveira

A tunnel to the south and a circular route

In three years, the Santo Ovídio station will no longer be the southernmost end of the Porto metro. Nor will F be the newest line of this transportation infrastructure. In the coming months, the metro will undergo one of its most ambitious expansions, led by a consortium consisting of Ferrovial and Portuguese construction company Alberto Couto Alves.

The expansion will be divided into two projects. On the one hand, the yellow line – D – will gain a new stretch of 3.15 kilometers south of Santo Ovídio. This new route will connect three neighborhoods in Vila Nova de Gaia: Mafamude and Vilar do Paraiso, Oliveira do Douro, and Vilar do Andorinho. The line’s construction, which includes a 770-meter tunnel and a viaduct, will then have three newly-built stations.

The second project will entail the construction of a new line, the pink G line. It will be a 3.1-kilometer circular route entirely underground, connecting the Casa da Música and Plaça da Liberdade stations near the Azulejos station with various points near the riverbank, including several departments, a hospital, a maternity center, and the Praça de Galiza.

In all, this will be over six kilometers of connections for a project that no one thinks is impossible today. Rather, it’s an essential connection between the hills of the second-largest city in Portugal.

There are no comments yet