There are buildings that can convey a sense of calm. Orderly, bright, open spaces that invite relaxation and increase our level of well-being. For centuries, architects and builders have accounted for the proportions and materials that are most suitable for creating pleasant buildings. In the middle of the last century, the ambition to understand the connection between emotions and structures went even further: it began to be studied scientifically. Thus, neuroarchitecture was born.

This discipline has come to understand what happens in our body when we go into specific spaces, and it has translated this information into objective data. The idea behind it arose precisely from a situation where architecture led to a unique train of thought. This story involves a biologist, the scientific method, and an Italian basilica.

In search of a vaccine

In the early 1950s, polio was highly feared in many parts of the world, and the United States was no exception. Several outbreaks reached epidemic status throughout the first half of the 20th century; the worst in the country’s history took place in 1952. Polio left thousands of deaths and people with paralysis in its wake; a solution to this infectious disease was desperately needed. The only truly effective way was to make a vaccine.

Many of the expectations and much responsibility for finding this vaccine fell on one person: biologist Jonas Salk. Since 1947, Salk had worked as director of the Virus Research Laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Medicine, and he had already participated in studies to develop a flu vaccine. Unlike many of his colleagues of the time, he was a staunch defender of this method of immunization. He was confident that vaccines were essential to curb the spread of infectious diseases, as well as in their ability to eradicate them.

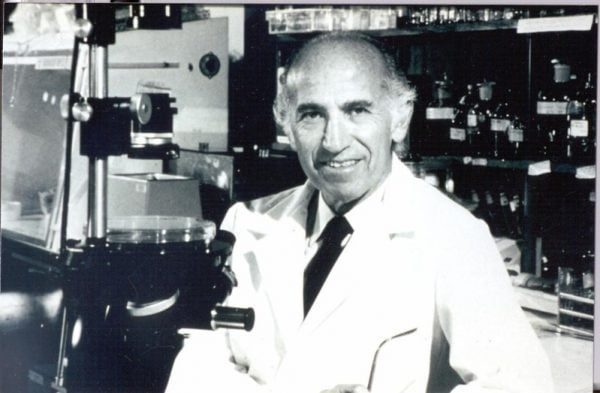

Jonas Salk in his lab. Sanofi Pasteur (Flickr)

Jonas Salk in his lab. Sanofi Pasteur (Flickr)

Determined to find the one that would bring polio to an end, he worked for years in a dark laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh. Though he seemed to be close to the solution, he couldn’t reach it. After numerous attempts, he was forced to face reality: he was stuck.

To take a break from his research, Salk decided to go on vacation in Italy. While enjoying time away from work at the Monastery of Saint Francis of Assisi, the definitive idea came to him. Away from his dim laboratory, he finally found the way to create the polio vaccine.

Space and mind

When he returned to the United States, Salk confirmed what he already expected: his idea was correct. Sure of its efficacy, he even inoculated non-infected people, his laboratory colleagues, himself, his wife, and their children. In 1954, the vaccine was declared to be safe, and by 1956, it was fully available for use in the United States. In just two years, the number of polio cases dropped from 45,000 to 910. Salk decided not to patent the vaccine, which began to be used around the world.

In addition to the satisfaction of finally finding the way to stop polio, Jonas Salk brought an important conclusion back from Italy: the basilica’s architecture and atmosphere had been crucial in helping him organize his ideas and think clearly. “The spirituality of the architecture there was so inspiring that I was able to do intuitive thinking far beyond any I had done in the past. Under the influence of that historic place I intuitively designed the research that I felt would result in a vaccine for polio. I returned to my laboratory in Pittsburgh to validate my concepts and found that they were correct,” he explained years later.

Convinced that buildings could influence thought and foster other great ideas in the future, the biologist founded the Salk Institute along with architect Louis Kahn. This scientific institution located in La Jolla (California) seeks to encourage creativity in a collaborative environment. The creation of this space, where the very design aimed to promote productivity, ended up laying the foundations for neuroarchitecture.

The Salk Institute in La Jolla. Adam Bignell (Unsplash)

The Salk Institute in La Jolla. Adam Bignell (Unsplash)

What happens in our brain?

Today, advances in neuroscience allow us to understand how our brains analyze the space around us. There are technological innovations that can measure people’s brain activity when they are touching or observing different materials and structures, and big data and machine learning solutions can handle large amounts of data.

All this information can be used by architects to create spaces that improve people’s well-being or favor certain types of activities. Lighting, colors, architectural forms, even ceiling height – these all influence the way our brain works.

Natural light, for instance, boosts concentration and relaxation. The colors most present in nature (green, blue, and earth tones) help us relax, reduce stress levels, and increase the feeling of comfort. Rooms with higher ceilings are also thought to be more conducive for creative or abstract activities. Lower headspace helps us pay more attention to small details. That is why artists’ studios tend to have the highest ceilings while operating rooms are in tighter spaces.

Rooms with lots of natural light and natural materials encourage creativity. Harprit Bola (Unsplash)

Homes, offices, hospitals, and schools. Today, any building can be designed and built following the principles of neuroarchitecture so that its forms and materials help improve the well-being of its occupants and, just as Salk wanted, to increase their potential.

There are no comments yet