In 1963, a neighbor in Turkey’s Cappadocia region knocked down a wall in his basement and found what looked like a large underground gallery. And it was just that: the ancient city of Derinkuyu, at least 18 stories deep and with the capacity to shelter thousands of people.

Beyond the maze of Derinkuyu and Cappadocia, where volcanic soils sometimes make digging easier than raising buildings aboveground, the world is full of vast underground systems. These were built to escape extreme temperatures, provide shelter from attacks and invasions, or just make the most of the space hidden underneath our feet. The catacombs of Paris and Rome, the city of Mamata in Tunisia, the village of Kariz in Iran – these are just a few examples.

However, not all great underground cities require us to travel back in time. They are also still being built today, often for the same reasons as they were thousands of years ago.

Toronto’s PATH

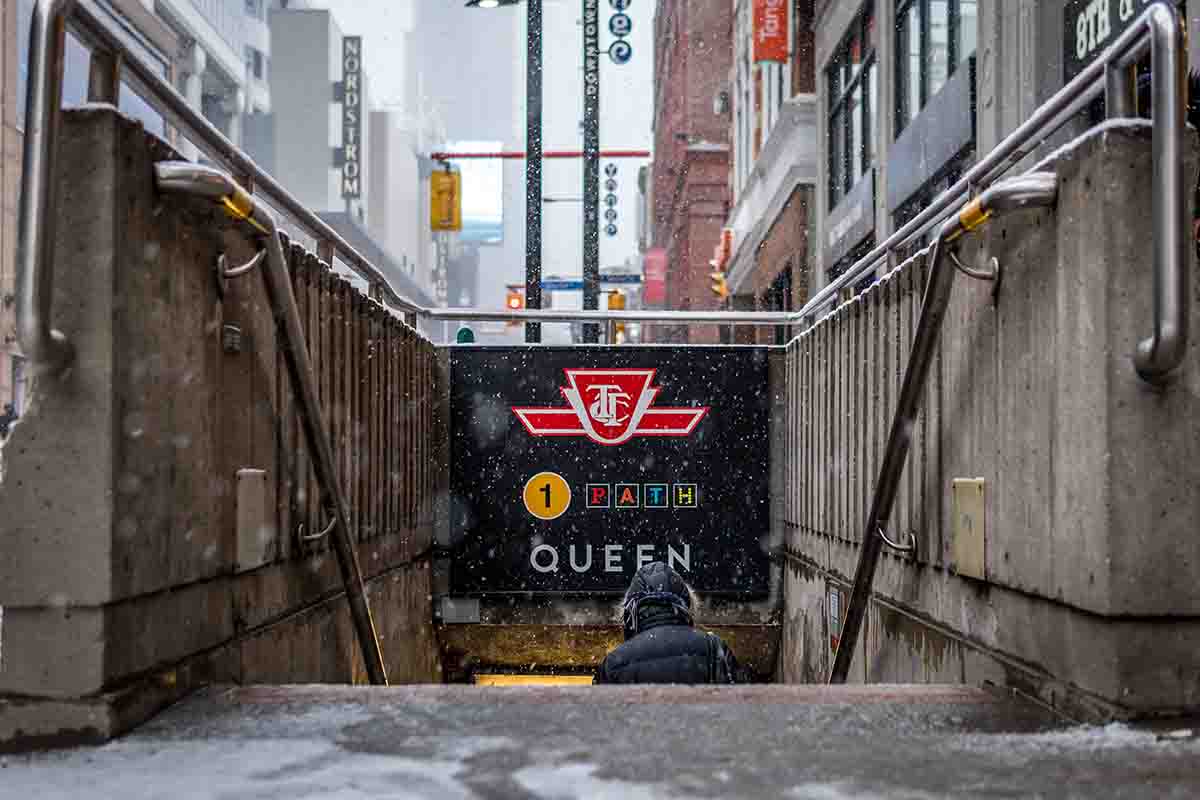

At a latitude of 43 degrees North and temperatures that easily plummet to 10 degrees below, the city of Toronto (Canada) has numerous options to take shelter during the coldest months of the year. One of them is the PATH, an extensive network of mostly underground pedestrian walkways.

Construction on Toronto’s first underground road dates back to 1900, when it was dug to connect businesses. By 1927, there were already five tunnels in the city center; throughout the 20th century, walking underground became increasingly popular with the citizens of Toronto. Finally, in the 1980s, the city government promoted the development of the tunnel system that we know today.

The PATH stretches over 30 square kilometers under downtown Toronto. Its galleries contain restaurants, shops, and numerous leisure services. It is a fundamental part of the city, directly connecting with more than 75 buildings, six subway stations, and many popular spots (such as the Hockey Hall of Fame or the Roy Thomson Hall).

But the truth is, Toronto is not the only city in Canada that has an underground system. The RESO network in Montreal connects metro stations, large hotels, nearly a thousand shops, and multiple office buildings. In addition to hosting much of the life of the city, it is a must for tourists and visitors.

Helsinki’s underground life

A large swimming pool, a rock-hewn church, shops, museums, and galleries that connect different parts of the city. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, Helsinki (in Finland) also has a large underground surface that is present in the daily lives of its inhabitants.

The idea of making a second version of the city underground dates back to the Cold War, when Finnish leaders considered options to protect themselves from neighboring Russia.

Today, the city has a plan to update this system and optimize urban space. “The ‘Helsinki City Plan’ proposes a denser construction, and the expansion of the city will make it necessary to transfer some of the operations underground and use the underground facilities more efficiently,” the city council’s website explains. Another major underground expansion plan involves creating a tunnel to link Helsinki with Tallinn (Estonia) by train.

Gardens under New York

In recent years, the possibility of giving the densest urban environments in the world a break with underground leisure spaces has been studied. One example is the Lowline, a plan to bring life back to a historic streetcar terminal on New York’s Lower East Side.

The Lowline is an underground park lit by solar technology. A system based on skylights, parabolic dish collectors, and reflective surfaces introduces enough light for plants, trees, and grass to grow underground. Lowline’s creators are trying to create a new type of public space that reclaims historical sites and turns them into green spaces.

The station, built in 1908 and abandoned 40 years later, still has its old cobblestones, train tracks, and large vaulted ceilings. This choice for the project was no accident: the area where it’s located is one of the least green spots in the city.

Over the last decade, studies and pilot tests were carried out that confirmed the project’s viability. It is currently paused and awaiting funding, and its founders are exploring the idea of taking it to other cities.

The Mexican groundscraper

“The Historic Center of Mexico City is in a desperate need of a programmatic make-over. New infrastructure, office, retail and living space is required but no empty plots are available. Federal and local laws prohibit demolishing historic buildings and height regulations limit new structures to eight stories,” Mexican architecture studio Bunker Arquitectura (BNKR) explains.

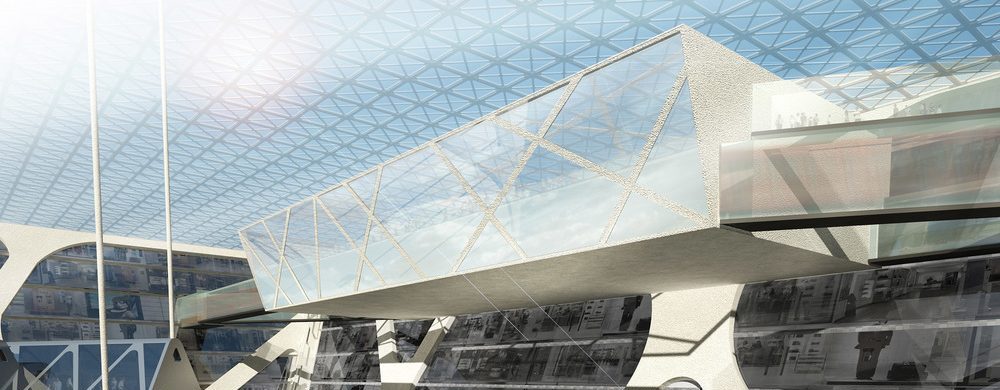

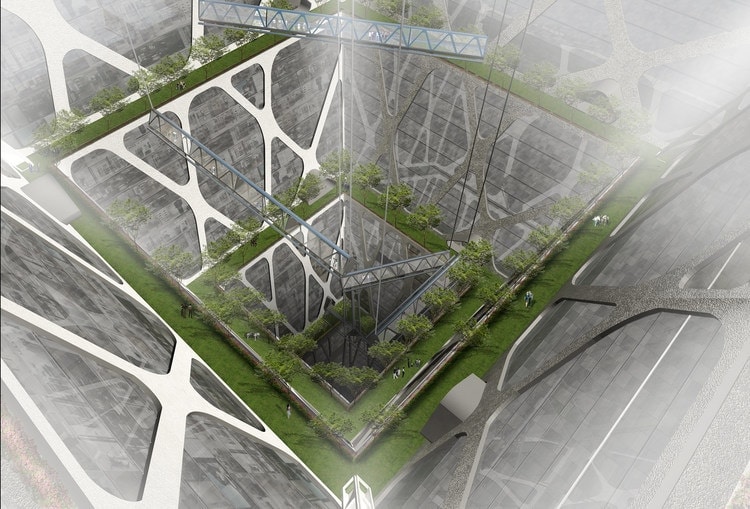

Their proposal? Building down. The Earthscraper is a project for a skyscraper in reverse in the shape of an inverted pyramid, which goes up to 300 meters deep under the Zócalo of Mexico City. This project (which was never approved) proposes a building with a void in the center so that all spaces have natural lighting and ventilation. So as not to lose space for life on the surface, it would be covered with a large glass floor.

The truth is that underground constructions are beneficial in places with extreme climates. Being underground, the temperatures are more stable and temperate. The town of Coober Pedy, Australia, is a good example: there, most of the residents live in old, rehabilitated mines to protect themselves from the high temperatures. In countries like Spain, underground constructions were also a solution for centuries to escape the heat.

However, the idea of proposing underground constructions in large cities as a solution to overcrowding has drawn much criticism. The first is the possibility that it could lead to segregation. That is, a society where wealth ends up determining who lives above and below the surface.

There are no comments yet