Common sense tells us that ownership of a piece of land includes ‘everything that is there’, in particular the earth and what we can build on it. However, when limits are put to the test, for example by building to extreme heights, or excavating well below the subsurface, things are no longer that simple.

While property limits, in terms of buildings and plot perimeters, tend to lead to conflict, at least on paper a map or land registry record should be able to locate the boundaries without too much margin for error. Even so, in Spain every year there are still thousands of conflicts that have to be resolved, mainly because information is lacking, the information is wrong, or conflicting information exists. There are errors in topographical registers, poorly geo-referenced data, imprecise aerial photographs, and sometimes the cadastral information has been poorly defined.

That said, one of the issues less frequently discussed is how far does ownership extend vertically, and the question is valid in both directions, upwards and downwards. Bringing our imagination into play, we could be speaking from a purely geometrical, mathematical perspective, from the ground floor of a building towards the centre of the earth and towards interstellar space – somewhat peculiar concepts that have also changed with time.

FROM HEAVEN TO HELL

In order to understand how this concept has evolved we must refer back to Medieval times, to the origin of the phrase ‘Cuius est solum, eius est usque ad coelum et ad inferos’, or ‘whoever’s is the soil, it is theirs all the way to Heaven and all the way to Hell’. This definition is considered one of the oldest to entertain the idea of land and property, and it states very clearly that a land-based property had no limits in terms of height or depth. Today, however, we know that, mathematically at least, this would be more or less the equivalent of a prism with its point at the centre of the Earth, extending beyond the atmosphere and into outer space, and including an infinite volume of universe that, due to the rotation and orbital path of the planet, would be continually changing. So while it was not a very practical definition, it was a start.

WHERE DOES ‘ABOVE’ END?

Our modern interpretation of ownership has become more a question of interpreting the law rather than one of pure geometry or precise measurement. But these laws still vary, and not just from one country to another, but also according to state, regional and even local legislation. While, in technical terms, a property may be perfectly geo-referenced on a map and even the air that exists above the maximum height to which building on the property has reached (which is also limited by land laws and other applicable laws) could be considered part of the property, height limits are a fuzzy issue that may be better defined as ‘the height that is required for reasonable enjoyment of the property’.

As an example, a drone taking photographs or making noise above a home could be considered to be ‘invading the property’ (or its ‘airspace’), something that most people in the world consider reasonable. But we cannot prevent, as some have attempted, an airplane from flying at an altitude of ten thousand metres along the same vertical, as this is considered public space, something equivalent to a ‘road in the sky’. The exact limit, however, is not always the same. In many countries it is set at around 100 or 150 metres (500 feet) above the building in question, the airspace from this point on belonging to everyone.

This laxity in the definition of these limits is even more curious when they are applied to the vertical limits of sovereign territories. Neither have strict limits been internationally established for the vertical extent of the ‘sky and airspace’ belonging to a country, in contrast to the situation with the oceans and ‘international waters’, which are legally established. While some set this limit at 30 kilometres, the normal altitude for airplanes and balloons, others set it as high as 160 km (100 miles), the point at which satellites begin to orbit. While most of the time this vast aerial void is free of traffic, and few of us are aware that airlines have to pay for every mile their airplanes travel over the various countries (an air traffic control issue that makes this a monetary matter, rather than something merely conceptual), the fact is that some airlines prefer to fly further in order to save huge sums every year. It is not yet clear what will happen when low-orbit space flights become as common as transatlantic flights.

A MORE IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS OF THE QUESTION

Image: Farringdon Crossrail (CC) Alvy

Back on Earth, an examination of the issue from another perspective may lead us to ask ourselves ‘What happens with what lies beneath the surface of a property?’ We own buildings with basements, parking garages, foundations and other installations, and underneath our cities we travel every day in metro and other road traffic tunnels, many of which could be compared to underground motorways. We also build many infrastructures that require perforation, such as water and gas mains, sewers, electrical and fibre-optic cables, etc., in addition to security installations such as vaults or bunkers, not to mention someone who buys land with water, oil, or precious minerals hidden below the surface.

In this case the obvious solution would be to differentiate between ground and underground. While one of Spain’s oldest laws states that ‘The owner of a tract of land is the owner of its surface area and what lies beneath it’, we must admit the issue requires much clarification. For example, while ‘subsurface’ is understood to mean everything that lies below ground level, it would appear obvious that whoever owns a piece of land is free to make ‘reasonable use’ of whatever lies underneath that land, for example to build basements or parking spaces or to lay foundations. But from a certain point on, or downward, the ground and all it contains is considered public domain. This is not always the case, however. In Mexico, for example, what lies underground is not considered private property, and in Australia, where there was originally no limit, a change in legislation has established this at 15 metres.

When we speak about ‘reasonable use’, of course, it all comes down to who interprets the law in the event of a conflict. Some cases are regulated by other pertinent legislation, such as the use of subterranean water, whether this is for the purposes of extracting water for wells or because the planned surface activity will affect the quality of the water simply because of where it flows. Something similar occurs with hydrocarbons and other mining materials that may be present. One of the most regulated areas is that of archaeological ruins, which often cause projects to be put on hold because of the cultural value of what has been found underground.

There have even been proposals to the effect that, in special cases, the ground and the subsurface may be considered separate, distinct ‘registered properties’, which would facilitate expropriation for the purposes of putting the subsurface to other uses, for example for urban planning requirements – imagine a large, subterranean train tunnel crossing a city. Who can say whether or not, in the future, laws will have to be changed in order to differentiate between subsurface adjacent to a property and deeper subsurface, so that the two can be treated the same way as airspace over buildings is treated today.

In some cases the legal issues are more complex. For instance, when a well-known company such as The Boring Company, headed by entrepreneur Elon Musk, has the idea to create giant networks of tunnels underneath cities like Los Angeles, there are many considerations, primarily that of not bothering the neighbours and complying with all work safety and environmental norms – objectives that can be achieved without excessive hardship simply by being meticulous. But this type of installation is quite different to a tunnel built by a local council for the purposes of public transport, in that the latter is essentially a private transport system that the general public will pay for when they use it in the future. At the end of the day it is more akin to a toll road than a public street, though the subsurface cannot be considered exactly the same way as the terrain used for a motorway as it is not limited by ‘flatness’ and is not owned by a particular individual. Despite the absence of better legislation and definitive decisions, some cities have already shown their support in the form of temporary concessions during an ‘experimental trial phase’ while they wait to see how things turn out.

Image: Project Iceberg – Londres / British Geological Survey.

LIKE AN ICEBERG ON LAND

An interesting article in The Guardian dealing with the problems relating to ownership of the subsoil mentions London’s Project Iceberg, an appropriate name for a project designed to properly map and catalogue all that exists in the city’s subsurface – which at times can appear to exceed that which exists overground!

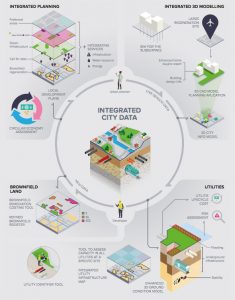

The project is being handled by the public organisation British Geological Survey and includes geological data relating to the terrain as well as the cataloguing of the more than 1.5 million kilometres of water, sewage, gas and electrical installations that, along with other elements, comprise the subterranean infrastructure of the city. The result will be far more precise and detailed maps and photographs in addition to extensive databases of information relating to the materials comprising the terrain at any specific point. The ability to pinpoint the location of all infrastructure elements will also allow for the creation of 3D models of the city, which can be used to quickly locate any resources required during construction works and improve the planning of these works in the future.

We live in interesting times; times in which our towns and cities and the properties that these contain are much as they always were, but in which the limits of these, whether we are looking upwards or downwards, have been extended thanks to the new possibilities offered by technologies and engineering.

There are no comments yet