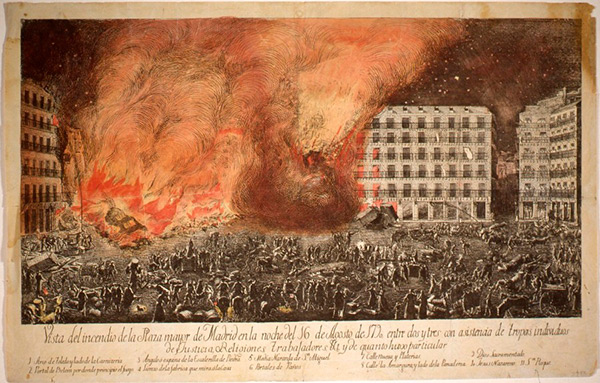

On a warm August night in 1790, Madrid’s Plaza Mayor would become the center of one of the worst fires the city had ever seen. On the latest episode of our podcast Sounds Like Infrastructure, we dive into the history of the square, find out how some clever tax dodging led to its creation just outside the city walls, and analyze the design decisions that were implemented in the wake of the fire to make sure the square would never burn down again.

Why did Plaza Mayor burn down in 1790?

On that warm August night of 1790, nobody noticed the fire at first, but then a thick smoke started making its way out of one of the shops and into the square, which, back then, was called the Plaza del Arrabal (arrabal meaning the city suburbs).

A small group of locals ran over and managed to pull the doors open, but as soon as they did, they realized their mistake. The air that rushed into the shop lit up the wooden beams which became a kind of kindling for the rest of the square. The fire quickly grew in size, stopping only when it reached parts of the plaza made of stone like the arch that led to Calle Toledo.

After just 3 hours, the fire had taken out the entire western wall of the square and attracted the attention of the King, Felipe II, who put the architect Francisco Sabatini in charge of the response. Amazingly, Sabatini took charge from a building in the burning square itself, the Casa de la Panadería. At his disposal were two groups of people: the locals and the military (because firefighters weren’t really a thing back then).

Without a team of dedicated firefighters, people worked furiously to put the fire out. They made human chains to transport buckets of water, but their efforts still weren’t containing the fire enough. So Sabatini, who noticed things becoming increasingly out of control, realized the only way of stopping the fire was to knock down the buildings in the path of the fire before it could burn them down.

After nine days, the fire was eventually put out, but what remained was a charred shell of the city’s most famous square. They decided they needed to rebuild the square.

How did they ‘fireproof’ Plaza Mayor?

Curiously, the fire in August 1790 wasn’t the first that took place in Plaza Mayor. It was actually the third. And after each fire, the square had been rebuilt. But something was clearly wrong with how they had been building it if it kept going up in smoke.

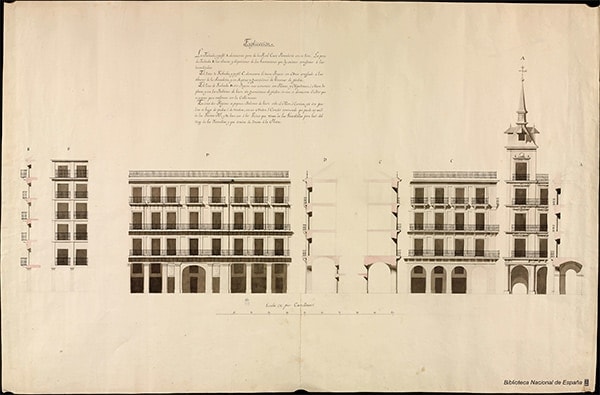

One of the main problems was that the square was built (and subsequently rebuilt) from wood. The architect Juan de Villanueva was brought in to fix this. He looked back at the previous fires and noticed that in all cases, the parts of the square that were made of stone had stopped the fire spreading. His conclusion was to increase the amount of stone in parts of the square like the arches, sills and ledges to break the momentum of a fire if one were to occur.

Among other things, Villanueva also reduced the height of the square by one story so that water would be able to reach the upper floors in the event of a fire; a problem that was evident during the fire of 1790.

Renovating the square today

The simple yet effective design decisions implemented by Villanueva meant the square still stands today. And in anticipation of its 400th anniversary, the Madrid City Council decided Plaza Mayor deserved some much-needed TLC.

Ferrovial was brought in to carry out the work, which included restoring the façades and roofs overlooking the square, refurbishing the arcades, and repairing the paving of the square and accesses among other work.

The work was carried out while the square remained open for business. And although that’s a simple sentence to say, the challenges involved to make this happen were huge. Keeping waiters, neighbours shopkeepers and tourists alike happy is one big challenge.

In the latest episode of Sounds Like Infrastructure, we detail what these challenges were and reveal the secrets and stories hidden within the walls of Madrid’s most famous square.

You can listen to the podcast (in Spanish) on your favorite platform or on Apple, Spotify and Youtube.

There are no comments yet