Chillin' in the Desert: 4 Modes of Passive Cooling, Ancient and Modern

14 of February of 2022

What do season 5 episode 2 of Black Mirror and the Ridley Scott movie Kingdom of Heaven have in common? You might be surprised to learn that they both demonstrate real-life examples of passive cooling, modern and ancient respectively. With climate change constantly in the news and the energy costs of cooling always one of the main challenges in a warming world, we are going to look at 4 ways, past and present, that humans can combat heat without burning fuel.

1. Indus Valley Civil Engineering

You might be forgiven for assuming that 2400-1900 BCE wasn’t the best time to be alive. Modern comforts that we take for granted had yet to be invented and you would be lucky to survive through puberty.

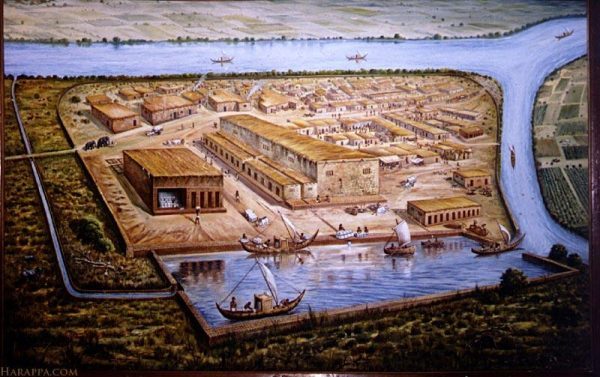

Nevertheless, if you were fortunate enough to live in one of Indus Valley Civilisation cities such as Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, or Lothal (pictured above) which are found in modern-day Pakistan, you might have had less chance of suffering from heatstroke than many of your modern descendants. While the Indus Valley itself isn’t technically a desert, it is surrounded by drier regions, and cities there today have summer highs of up to 38ºC which is more than hot enough for most of us.

Smart City Planning:

The engineering and city planning of the Indus Valley sites would be the envy of many modern cities. The streets were designed in a rectangular grid pattern of one and two-storey houses, that had their windows purposely oriented to make the best use of the wind currents in the area. This provided passive cooling via air flow through each home. Any survivor of a summer in a scorching urban area, without the luxury of air conditioning, cannot help but be envious of this architectural foresight.

2. Qanats, Bâdgirs & Yakhchāls = Aqueducts, Windcatchers & Ice-Houses

The Ancient Persians had something even more impressive than passive air fans: Passive air conditioning and refrigeration, a technology that was used across their empire during their own reign, by late-comers such as Saladin, and is still used today.

Qanats:

In Iran you can find ancient qanats, underground aqueducts dug through the rock with access shafts dug vertically at regular intervals, dating back around three thousand years. These connect alluvial aquifers to cities and agricultural areas to allow for irrigation. The underground water channels are estimated to reach around 384,400 kilometers end to end; the distance to the Moon.

Bâdgirs:

In the cities, they took this a couple of steps further: Bâdgirs (or windcatchers) look like large ornate chimneys, but their role is quite the opposite; they sit atop buildings catching the outside wind. The wind above the building is faster than the wind at ground level, which turns the badgir into a large straw that pulls air up from inside the building from the basement.

The basements receive their air from the underground qanat systems, where (thanks to the straw-like effect of the badgir) hot air has been pulled down from the surface through the access shafts along the qanat’s trip to the city, and has been cooled by proximity to the mountain water. What’s the result? Modern windcatchers such as those on the Zion National Park Visitors Center in Utah showed a reduction of sixteen degrees celsius (23ºC) in the building compared to the surrounding outside temperatures (39ºC). Not too shabby at all.

Yakhchāls:

If that wasn’t enough, these same systems were also used to make and store ice. The Persians would freeze water to ice in the three months of Persian winter and pools would be filled with water from the qanats.

At night, when the air temperatures were at 5ºC or less, radiative cooling back into space would chill the water until it froze (like how frost forms on grass even when temperatures remain above zero on clear nights), being broken up and then refilled with water and refrozen, building a thicker and thicker layer.

Once it had reached the desired thickness, the ice was cut up and then stored and insulted within a Yakhchal (Persian for ice house), a conical or domed brick structure, losing only 20% of its mass during the other nine months of the year.

3. La Casa del Desierto

La Casa del Desierto you might recognise as one of the backdrops to episode 2 season 5 of Black Mirror. It’s a venture by Guardian Glass to test the feasibility of their modern materials to passively maintain liveable temperatures in extreme environments. Which extreme environment did they choose? An isolated hilltop in Gorafe, Granada, fifteen minutes’ drive down a dirt road into the desert. It can reach up to 45ºC in the summer and as low as -10ºC in the winter.

Self-sufficient:

The inside of the 20m2 house however boasts a pleasant 18-28ºC year-round, entirely disconnected from mains electricity and water, utilizing only its 26m2 of solar panels to generate energy for the three rooms that make up the living area. The house is built essentially like a giant, futuristic, triangular oreo, with an exceptionally thick cream-part made of insulating glass (that’s the bit you live in).

The wide, reflective roof that juts far over the living area diverts the energy of the Sun away during the hottest part of the day in summer, while the glass walls let the less intense light of the morning and evening warm the house.

4. Night-Sky Cooling in the Middle of the Day:

Remember how the Ancient Persians were freezing water above 0ºC? Those pools were effectively radiating their excess heat back into space through radiative cooling. Pity it only works at night, right? Wrong!

Professor Aaswath Raman, a Canadian applied physicist and engineer, brings us almost full-circle in our journey. As a young boy, he would visit his grandparents in Mumbai, India and wonder how they could cope with the summer heat without air-con. Now as an adult, he has realized the carbon cost of cooling.

Anti-Solar panels:

His company, SkyCool Systems, has developed a cooling panel; something that looks like a solar panel, but repels the Sun’s energy rather than absorbing it. Using a multilayer optical material more than forty times thinner than a human hair, these panels simultaneously reflect sunlight and also radiate heat energy from within a building out into space.

These clever panels exploit the 8-13 µm wavelength of infra-red light that largely bypasses absorption by atmospheric gases. The technology has already been used to reduce a supermarket in California’s yearly refrigeration bill of $40,000 by 14.5%.

The current system still requires water flow, which means energy consumption, and the effect is reduced by inconveniences such as cloud cover or fog. Raman however, is hopeful that as the system is refined, this will be the first of many steps on the road to a more sustainable future.

From ancient to modern, these are just 4 of the ways that humans have found to beat the heat. If the ever redder and angrier lines on climate change news stories tend to stress you out, you can take some solace in the knowledge that for thousands of years, there have always been those with engineering know-how, out there playing it cool.

1 comment

Juan José Ahumada

03 of March of 2022

Very interesting, It is amazing how we save energy