For millions of people in different cities around the world, distances are measured in time. We calculate how long it takes to get to work, the gym, the supermarket, or the nearest subway station, counting it in minutes. Often, these distances are so long that the days seem to get shorter, and these minutes are wasted, lost in travel.

Some cities have decided to turn this situation on its head and get time on their side. The premise is based on chrono-urbanism, a new model that ensures that everything we need on a daily basis – places to live, work, shop, play sports, and enjoy leisure time – is available within a few minutes’ walk or by public transit.

The 15-minute city

Chrono-urbanism is a new urban model that aims to decentralize cities. This would mean the end of the urban model with business, residential, commercial, and leisure areas, each separated by long distances. In this model, citizens spend much of their time every day getting to where they work, shop, or play sports. All told, this system is inefficient.

The new model imagines cities that are organized around small nuclei, where every neighborhood and district have the services needed for day-to-day life. In these cities, the pace of life is no longer determined by rushing around, long distances, and traffic.

The idea behind chrono-urbanism was popularized by the mayor of Paris, Anna Hidalgo, and her plan to turn the French city into La Ville Du Quart d’Heure (or the 15-minute city). The term was coined by Carlos Moreno, an advisor to the mayor’s office, who was committed to transforming the capital of France – a city that is spread out over 100 square meters and is home to several million people – into a close-knit city.

The 15-minute Paris. Paris en Commun.

However, the concept of chrono-urbanism is rooted in demands that go beyond the streets of Paris. By 1920, now a century ago, American urban planner Clarence Perry proposed the concept of neighborhood units. These small communities were delimited by roads for traffic, leaving the inner streets free for pedestrian spaces and four basic elements: schools, parks, shops, and residential buildings.

The benefits of chrono-urbanism

The 15-minute city first emerged in order to reduce the environmental impact of traffic on the streets of Paris. This was done by limiting travel in private vehicles and promoting pedestrianization, public transit, and the addition of bike lanes. However, the model offers many other benefits.

Deloitte Consulting highlights the creation of a sense of community, for instance. According to their analysis, these types of cities improve the livability of neighborhoods and promote participation in issues related to the community. By having more free time and enjoying the surroundings and their advantages, cities become friendlier and less stressful, places where cooperation is encouraged.

Pedestrians crossing a city street. Behzad Ghaffarian (Unsplash).

Rejuvenating the economy and democratizing the housing market also come into play. In recent years, we have seen how gentrification has replaced inhabitants in numerous neighborhoods and how locals stop running family businesses, giving way to shops destined for new audiences. One of the premises of chrono-urbanism is for neighborhoods to offer solutions for people of all ages and economic statuses. This way, Deloitte points out, they will become more affordable places to live.

Finally, improving the quality of life and health for residents is at stake. What’s necessary to achieve all this? Deloitte identifies the following as essential factors:

- Ensuring easy access to medical services and food.

- Building multicultural neighborhoods with different types of housing and various levels of affordability.

- Having offices, commercial spaces, and a selection of hotels.

- Having abundant green spaces.

- Creating corridors for pedestrians and cyclists.

- Reducing the ease of car travel (for example, only having one-way streets or limiting the number of parking spaces).

From Paris to Stockholm

The best-known example of chrono-urbanism is the 15-minute city of Paris. It’s based on four pillars: proximity, diversity, density, and ubiquity. It’s not the only one, though: in Sweden, for example, the plan is to implement the one-minute city model nationwide.

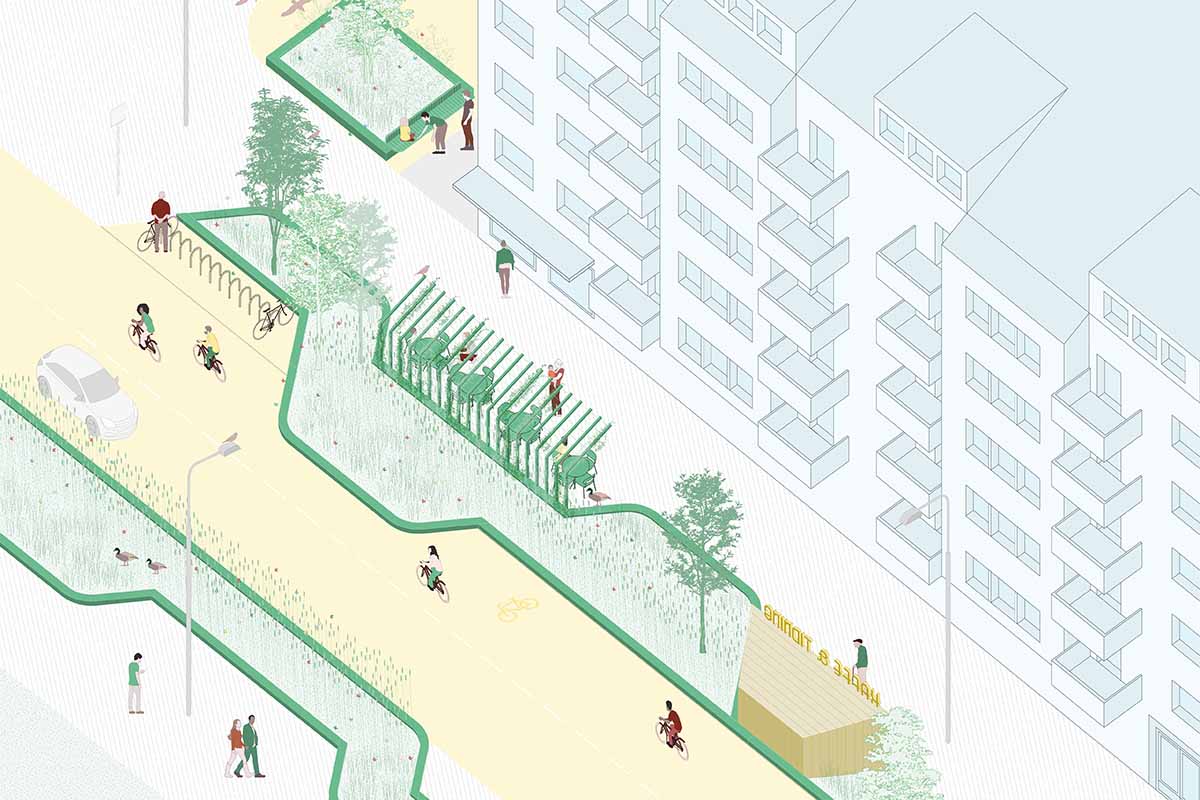

The Scandinavian model (which is based on the Street Moves movement) goes one step further than the French model, proposing urban layouts based on neighborhood life. The goal is for residents themselves to decide how to use the spaces on their street or block through consultations and collective workshops. This, its creators point out, encourages the use of shared spaces and cooperation. Sweden plans to implement this model not only in its capital, Stockholm, but on every street in the country by 2030.

Image from the Street Moves project in Sweden. Utopia Architects.

Chrono-urbanism has also had an impact in the United States. In Portland, Oregon, an approach with a social perspective has been proposed, aiming to encourage the creation of affordable housing, more public transit, more pedestrian spaces, and, ultimately, more inclusive and community-based neighborhoods. Portland’s plan is for 90% of city residents to be able to walk or pedal to meet all of their daily needs (except those related to work) by 2030.

Another example can be found in Spain, in Pontevedra. While the city’s plans never used the term chrono-urbanism, they still let residents get anywhere on foot in just a few minutes, and they encourage cohesion and minimizing social differences.

Chrono-urbanism is therefore a solution for making cities more close-knit, friendlier, and more humane. In these cities, any neighborhood is a good place to live, no time is wasted on endless trips, and the distances don’t determine its residents’ quality of life.

There are no comments yet