Hard, exposed, raw, angular, gray, sometimes unpolished, always sincere, and as widely loved as it is hated. Brutalist architecture is an artistic expression of architecture that forges toward a new type of urbanism, one that’s stricter and neutral in terms of color. A visual example of hardness and simplicity that’s as apathetic as it is elegant. What is Brutalist architecture?

Why is it called ‘brutalist?’

The term ‘Brutalism’ — suggestive as it is of a sort of violence – comes from the French béton brut, which literally means ‘raw concrete .’ However, that element of hardness, the visible preservation of structural elements and angular geometry, goes hand in glove with the word ‘brutalist.’

The French term, béton brut, is used to describe a type of finish that leaves the concrete ‘unfinished’ once it has been cast. This results in the patterns and seams printed by the formwork being exposed. It is important to highlight that béton brut is not a material per se but a way of working with concrete that later led to architectural expression.

The origin of Brutalism as architecture

Even though it has a French name, Brutalism emerged in the United Kingdom during the post-war period. World War II had left many cities in ruins, and housing options became conspicuous by their absence. Rebuilding the country was necessary, and urgently so in this particular regard. Brutalism became an ideal tool to this end thanks to its low costs.

Unlike conventional English houses, including both modernist functional and neo-Renaissance or Georgian buildings, Brutalist buildings allowed for a much faster execution speed; it wasn’t necessary to make stylistic adjustments once the concrete was poured.

At this point, we should note how Brutalism also took on industrial elements like exposed brick walls (which previous styles always covered). That’s why many English houses of 1950 boast a characteristic factory style that would later become something of a global norm with postmodernism (the ’80s and ‘90s).

Why the French name? While the United Kingdom was rebuilding its cities, modernist architects Auguste Perret and Le Corbusier began to work with the exposed concrete technique. In 1952, Le Corbusier would finish the first Unité d’Habitation, a residential building with a modernist style but Brutalist finishes. He didn’t conclude this project with much pomp, given the lack of quality.

Examples of Brutalism and Brutalist architecture

The headquarters for the Bank of London and South America (Buenos Aires) was built in 1959 with a clear Brutalist streak. Over the decade that followed, it was the most identifiable Brutalist building in the country and still holds a special place as an Argentine monument.

In 1968, construction on the Torres Blancas in Madrid, an Organic Brutalist building characterized by a system of elevated curves along 23 floors. These are luxury homes.

Completed in 1968 (the image is from 1973), the Boston City Hall it is a Brutalist building that was particularly controversial at the time because it did not follow the traditional norms of American city halls.

The Geisel Library (1970) in San Francisco is one of the most prominent examples of Brutalism with significant glass surfaces. While it appears to be a light structure supporting the sky from a distance, only the concrete finish can be seen from below.

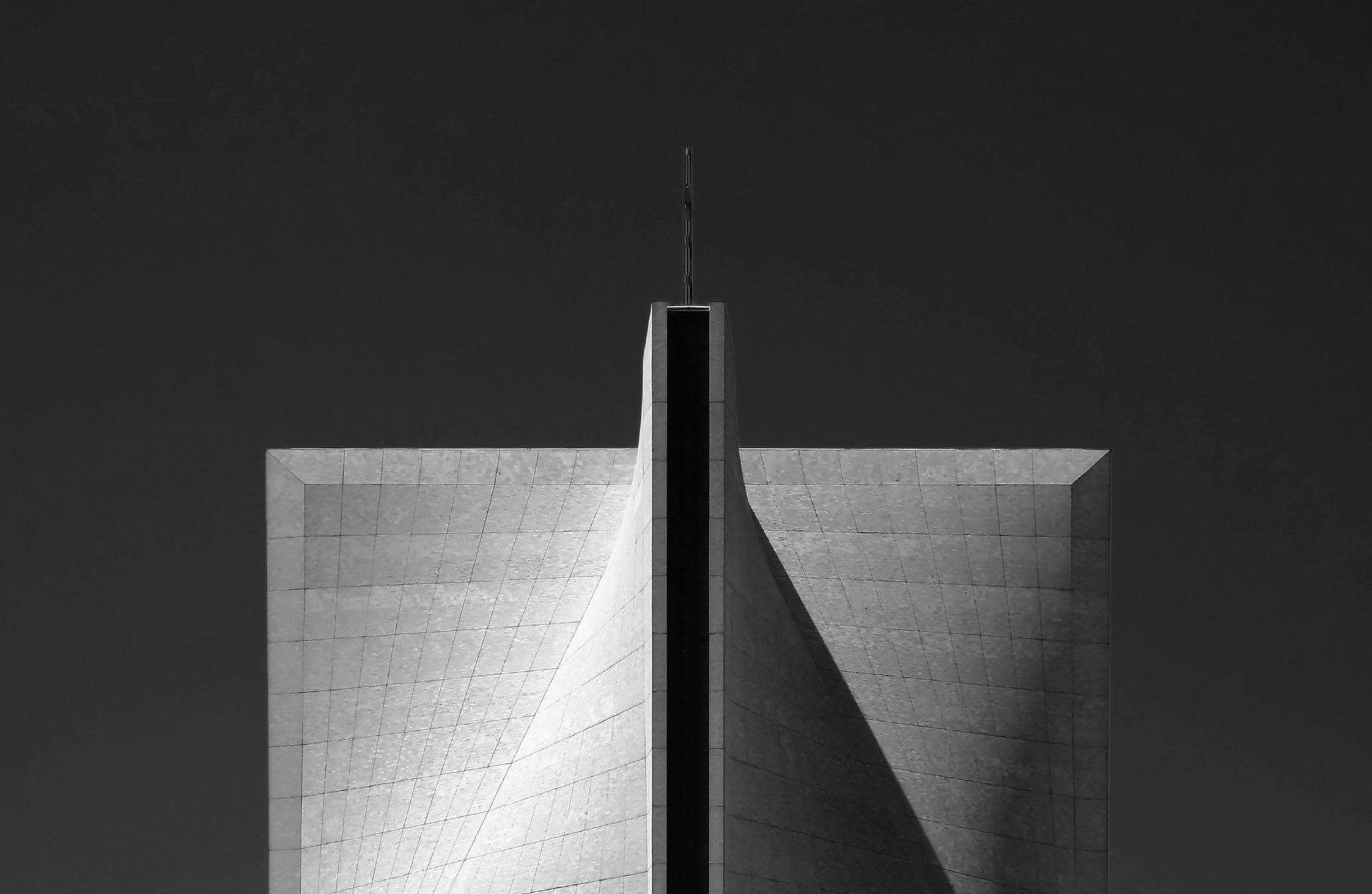

Due to the building’s intended use, the Cathedral of St. Mary of the Assumption (1971) is unique as a Brutalist building. This is a unique building, unlike anything else in the world. Its wide floorplan narrows as it rises from the corners, forming a cross that’s only visible from above.

In 1973, the Alt-Erlaa residential and commercial park was completed in Vienna. It has characteristic high-rise housing, where the first ten floors have terraces integrated into a vertical green forest.

A year later, in 1974, work finished on Choux de Créteil (the Cabbages of Creteil) in the city of the same name. The balconies of these five residential buildings are vegetable-shaped, reminiscent of the region’s horticultural past.

Between 1965 and 1976, the Barbican Estate was built in the city of London in an area that had been devastated by World War II. It includes 2,000 homes and was announced with great fanfare in the ’70s as a smart housing solution. About 4,000 people live in its modules and towers.

The Palika Kendra (1984, New Delhi) is one of the most famous Brutalist court buildings located in India. With its 21 floors, it was the tallest building in the country for a few years. It is clearly inspired by the aforementioned Alt-Erlaa, though it serves as an administrative building rather than residential purposes.

Eco-brutalism and criticism of the use of concrete

Concrete is a material with high embodied energy and high CO₂ emissions compared to other materials. That is, it needs a lot of resources compared to brick, for instance. Leaving aside the aesthetic perspective, which is always entirely personal, it makes sense that postmodernist Brutalism has been the target of ecological criticism.

The two images in this section, the first belonging to a building in Switzerland and the second to one in Belarus, show facades and concrete finishes that could have been carried out with lower impact materials. Reinforced concrete is ideal for infrastructure and internal structures, but as a building envelope, it is far from low-impact.

In fact, structural concrete has one unbeatable advantage: by making high-rise buildings possible, it enables a medium-density, mixed-use urban environment that minimizes its environmental footprint (energy, water, raw materials, emissions). That said, concrete’s characteristics have advantages such as those described in eco-brutalism.

Eco-brutalism is an architectural movement that aims to link its structural advantages with vegetation and islands of biodiversity. While there is no doubt that neighbors would benefit from these new areas, the social cost of their emissions is not entirely justified – at least not if there are green areas at ground level. There are some interesting proposals, though.

The Interlace (2013) in Singapore offers one example of a complex system of buildings in the Eco-Brutalist aesthetic with some green on them, but their finishes are not made from the exposed concrete that was characteristic of Modernist Brutalism. By raising the housing blocks off the ground, the soil is freed up for green areas. Eco-Brutalism has an example to follow with this municipality-building.

Images | Simone Hutsch, Iantomferry, Dan DeLuca, Jose Javier Martin Espartosa, NARA, Victor Baro, Andrew Louis, Nick Night, Paul Fleury, Stephencdickson, Ricardo Gomez Angel, Ivan Aleksic, Matej Sajgal, CHUTTERSNAP

There are no comments yet