When the Little Prince drew what was clearly a boa after eating an elephant, the adults didn’t quite understand what he meant. “What’s so scary about a hat?” they asked. He had to draw it again, showing the elephant through the snake’s skin. This time, they did see the elephant, but they didn’t know what to make of his artwork. The Little Prince decided to abandon what, according to him, would have been a glorious career as a cartoonist.

As we grow up, we adults lose much of the imagination we had as children. But this does not mean we stop seeing faces and figures where there are none: in fact, we do so quite often and unconsciously. This is due to pareidolia, the phenomenon that makes us see faces and even expressions in objects, including buildings.

The relationship between pareidolia, design, and architecture is a close one, so much so that studies have been carried out to analyze our emotional response to buildings. Some architects – such as Japanese architect Kazamasa Yamashita – have created faces in their blueprints. We’ll tell you about what pareidolia is and its relationship with the world of design and construction.

What is pareidolia?

The term pareidolia comes from the Greek para (παρά), which means “similar to,” and eidolon (εἴδωλον), “figure” or “image.” It refers to a psychological phenomenon where a stimulus, usually an image, is perceived as something already known. In other words, it is that moment when our brain identifies the parts of an image as something familiar.

House with a smiling face (Pxhere)

The fact that pareidolia leads us to see mostly faces or shapes of people and animals is no coincidence: our brain tries to find meaning and logic in everything it sees, and it relates the new images to the ones we have filed in our memories. One of the elements we remember the most and pay the most attention to are faces, both of people and animals.

Thus, when we perceive a similarity between an object and a face, however minimal it may be, our brain suggests that we are dealing with a known element. Some theories suggest that it is an evolutionary trait that lets us humans (and other animal species) quickly recognize a threat. This would include the presence of a predator.

Pareidolia and design

No one would find it strange to see the shape of two eyes in the spotlights of a car or a face in a mailbox. The truth is, this similarity is often used to create products that inspire sympathy. A study conducted by researchers from the University of Strathclyde (Glasgow, Scotland) analyzes the implications of facial and anthropomorphic features in product design.

According to the researchers, pareidolia is a phenomenon that can occur accidentally, but it can also happen deliberately to provoke a certain reaction or response. It can be used to make a new technology accepted or more understandable (as in the case of robots, for example).

It is also good for projecting certain values, simplifying complex systems, and increasing the feeling of connection with them. There’s one example in car design: a car with large round headlights does not generate the same response as one with elongated headlights (which can be compared to the face of fast felines like jaguars or cheetahs).

Image of the elongated headlight of a car. Jonathan Gallegos (Unsplash)

Other research has also looked at how this emotional reaction influences the way we see, understand, and enjoy architecture. What if the mind subconsciously interprets the geometric configuration of different wall shapes as an expression of particular emotions?

This is one of the questions posed in the study ‘Pareidolia analysis of architecture: Reading the emotional expression of a building façade.’ In it, the emotional reaction generated by observing Villa Savoye by Le Corbusier and Robie House by Frank Lloyd Wright (at different times of the day) is examined. These houses do not look much at all like with human face. The most detected expressions were happiness, surprise, anger, and disgust.

Pareidolia: when houses have faces

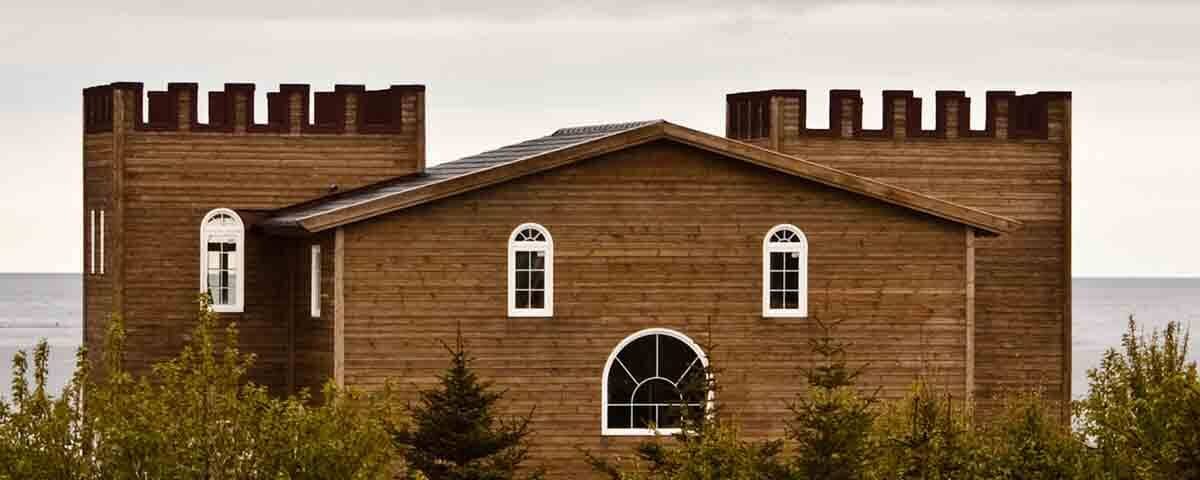

While it always depends on each person’s imagination, we could say that the world is full of houses and other structures with faces. Often, windows look like eyes., doors look like mouths, and the roofs are locks of hair that fall to the sides.

A face-shaped barn in the south of Ireland. Ingvild Sommer (Flickr)

Some architects take this one step further and consciously create faces in their designs. This is the case with Japanese architect Kazumasa Yamashita, the creator behind the Face House in Kyoto, among other famous works. A house with eyes, a nose, and a mouth.

The Face House in Kyoto. Brakeet (Wikimedia Commons)

As explained in the magazine ‘The Architectural Review’, Yamashita’s goal was to humanize a downtown street and give a different image to a building that was nothing more than a concrete block. The human faces of the house are also functional: the nose lets light into one of the rooms, and the mouth is a door to the street from one of the housing studios (its owner is a designer).

Other artists bring life and faces to buildings that already exist. Nikita Nomerz for example, paints faces on old abandoned buildings in Russian cities. Architect Federico Ballina enjoys seeing animal shapes in buildings by famous engineers and architects such as Eiffel, Utzon, and Wright; he turns them into funny illustrations in his album Archizoo – An architectural Pareidolia.

“When I was a kid, I wanted to be an architect, and now that I’m an architect, I would sometimes like to go back to my childhood,” Ballina writes. Pareidolia gives him the opportunity to let his mind wander freely and, unguided by rationality, draw a real zoo of architecture.

Main image: Building with eyes and mouth. Ingvild Sommer (Flickr)

There are no comments yet