Does our whole coordinates system come from the humble housefly?

01 of October of 2024

H2. E7. A9. Hit! In a game of Battleships, having a proper record of where you’ve launched your bombs it just as important as stopping your opponent from laying traps (and seeing where you’ve positioned your boats on the board). If logic and luck are on your side, you’ll end up uncovering the location of your opponent’s entire fleet, from the smallest ships to the submarine and aircraft carrier.

When the game’s over, and you’ve had enough of ‘hits’, ‘misses’ and ‘sunks’, you can then analyze the position of the two fleets on the coordinates grid. It’s an incredibly simple explainer showing how just two references can determine a position of a point in a space.

The concept was unveiled to the world by René Descartes in the seventeenth century, and has since set the course of the evolution of science. Cartesian coordinates are about more than a game of battleships: they’re used in everything from maps to the plans used to design roads, buildings and more. And it might well be that it all started with the flight of a humble housefly.

Descartes, disease and a fly

As legend has it, René Descartes had taken to his bed one afternoon, laying prostrate due to ill health. His entertainment? A solitary housefly, buzzing around the room erratically. As he watched the insect in flight, he reflected on the unpredictability of the movements, and the challenge recording the trajectory would entail.

But then he stumbled upon a solution. He concluded that to determine the position of the fly at any given time, it would be enough to position it on a plane, showing its distance to the floor and walls of the room. The concept of creating a reference system based on two graduated straight lines and four quadrants led to what we now know as Cartesian coordinates.

This little fly inspired Descartes to create his coordinates system. Jin Yeong Kim (Unsplash).

Whether this is what happened is hard to prove, but we do know that the life and career of Descartes was largely determined by poor health. The French philosopher, physicist and mathematician was born in 1596 in The Hague, where his mother had fled from an outbreak of the plague in her hometown of Nantes. Aged just 11, he was enrolled in a Jesuit school. He missed countless classes due to his various illnesses, but that did nothing to stop him from being an outstanding student who dedicated long hours to study and reflection.

His subsequent studies, military life and works as a philosopher and researcher were all marked by frailty. Numerous historians point to his time spent resting (and even some of his dreams) as fundamental to shaping his philosophy, principles such as “I think therefore I am”, analytical geometry, rationalism and his Cartesian method.

Portrait of René Descartes. Wikimedia Commons.

Cartesian coordinates in engineering

Descartes’ philosophical thought is based on the concept of the method; an orderly system on which we can build and base knowledge. The same applies to his Cartesian coordinates (named after him), which work as a base and system to represent a particular position. The development of the ‘Cartesian plane’, based on one horizontal axis and one vertical (X and Y) led to a significant advance in geometry.

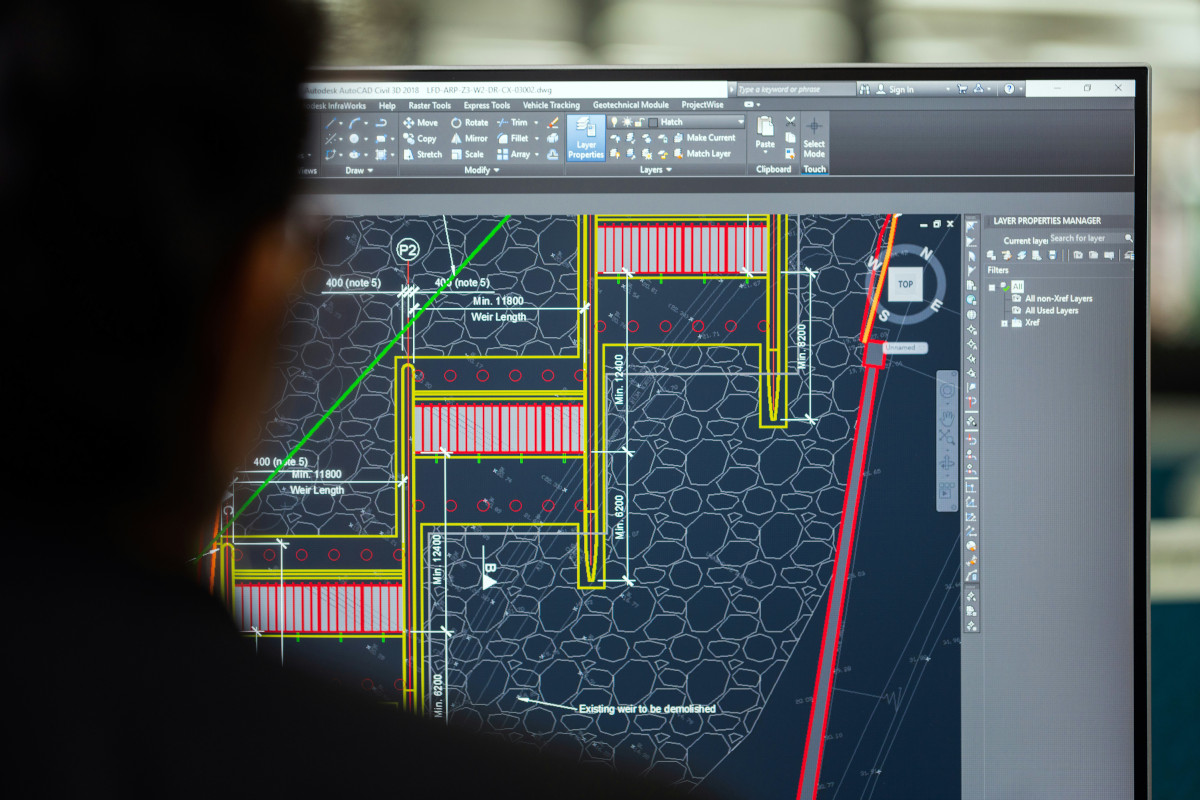

Engineering, architecture and design all use planes and geometry to draw up diagrams of real surfaces or structures on a flat surface. In engineering, the foundations laid by Descartes (which gave rise to other forms of coordinate systems) have numerous applications: they’re used to determine volumes and designs, ensure structures are strong enough (taking into account the resistance of materials), plan roads and routes, or examine the best ways to support a load.

Design and engineering programs are based on coordinate systems. ThisisEngineering (Unsplash)

Tools drawing on geometry and mathematics remain incredibly important to engineers and other professionals such as architects in the present day. These techniques, used throughout history, came to be described with a formula and reflected on a plane from the seventeenth century onwards—all, perhaps, thanks to a mathematical thinker’s fixation with the flight of a housefly. Descartes’ work contributed to the foundations of the modern scientific world.

Road routes also depend heavily on geometry. Deva Darshan (Unsplash)

In 1650, the philosopher died in Stockholm, where he had been summoned by Queen Cristina of Sweden. But his remains did not stay there: they were exhumed in 1676 and taken to Paris, moved again during the French Revolution, and repeatedly moved again for research, conservation and even to clarify Descartes’ cause of death. These posthumous trips went on their own journey; one that might well have been plotted on a map of Europe using the philosopher’s own coordinates system.

There are no comments yet