When Queen Alexandra of Denmark learned to drive a car, she had only recently ascended to the throne of the United Kingdom as consort to Edward VII. The 20th century was dawning, and her driving teacher hadn’t broken any records yet. The queen’s name was already in the history books. And her unknown teacher, Dorothy Levitt, would soon join her.

When the great-grandmother of the current Queen of England, Elizabeth II, learned to drive, that was still not a very common practice – especially for a woman. Her royal status helped her (and her daughters) enlist the services of Levitt. Levitt was an expert on cars by her early 20s, both behind the wheel and in terms of the mechanics of an invention that would change the world in the coming decades.

She liked teaching almost as much as speeding down the open road. Throughout her life, Levitt would break records on land and water, and she would become a leader in feminism and women’s independence. In fact, for six years, she wrote newspaper articles about women and cars. They would eventually lead to a book, The Woman and the Car: A Chatty Little Handbook for All Women Who Motor or Who Want to Motor, which would go down in history as the first reference for using a rear-view mirror.

Born to jewelers, sponsored by a pilot

Dorothy Elizabeth Levitt was not noble, but she was upper-middle class. That helped her at a time when many doors would open (or not) depending on one’s (social) place of birth. Born into a family of jewelers of Sephardic origin that had settled in Hackney, a borough of Greater London, Levitt experienced velocity early on while horse riding.

Not much more is known about her early years, but by 1901, she was already working as a secretary, which was considered an acceptable job for a woman of her class at that time. That’s how she was hired by the Napier Car Company in 1902, a manufacturer of luxury cars and racing cars. There, she crossed paths with Selwyn Edge, an Australian-born entrepreneur, cyclist, and pilot. He recognized her talent and quickly sponsored her.

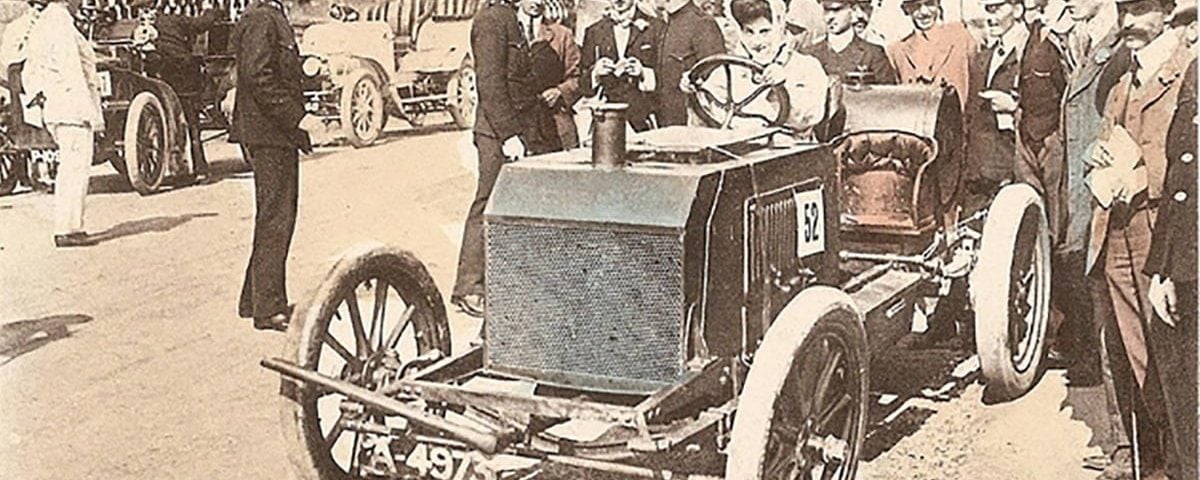

That same year, he sent her to Paris, where Levitt learned to drive, came to know the secrets of mechanics, and ended up falling in love with motor racing. It was on the way back from her stay in France, at the age of 21, that Levitt began teaching royal British women. By then, she had only one goal in mind: to become a great racing driver. In April 1903, she became the first English woman to participate in a car racing competition, but she fell far short of victory.

Dorothy Levitt was the first English woman to participate in a car-racing competition. / Wikimedia Commons

Dorothy Levitt was the first English woman to participate in a car-racing competition. / Wikimedia Commons

A 16-hp Gladiator and a rear-view mirror

Selwyn Edge was also the United Kingdom’s ambassador for the Gladiator car brand. So Levitt, as his pupil, became the face of the brand. Shortly after participating in her first race, she got in a 16-horsepower Gladiator to run the Glasgow to London Motor Trial, a points competition where she had to travel the 650 kilometers separating the two cities without stopping. Levitt only lost six out of 1,000 points total.

From that moment on, her career went hand-in-hand with the rapid evolution of engines. After winning her first speed competition, she participated in the Brighton Speed Trials in 1905 (one of the oldest races still held today). She did so at the helm of an 80-horsepower engine, which could reach speeds that were unimaginable at the time. Levitt crossed the finish line at 126 kilometers per hour (some 78 miles per hour), ahead of all the other drivers.

The following year, she climbed into a 90-horsepower Napier, reaching 128 kilometers per hour (80 miles per hour), the highest speed ever reached by a woman at that time. By then, she was already famous not only in the United Kingdom but throughout Europe, where she also won victories behind the wheel. In 1906, with a 100-horsepower Napier K5-L48, she would once again break her own record, reaching 146 kilometers per hour (90 miles per hour) in under a kilometer.

During that first decade of the 20th century, Levitt became as well-known for her skills as a pilot as for advocating women’s right to drive. She said that she wasn’t racing for the monetary prizes but for public recognition, and to set an example. In a weekly column in The Graphic newspaper, she debunked myths about women’s interest in mechanics and about the gender’s alleged difficulties in driving motor vehicles.

Levitt became a regular press feature in the first decade of the 20th century. / Sound Architect, YouTube

Levitt became a regular press feature in the first decade of the 20th century. / Sound Architect, YouTube

As a result of those columns, she would end up publishing a book with all of her advice and where she revealed all of her secrets. Among them was her habit of using a hand mirror during races to know what was going on and keep an eye on her competitors. The year was 1910. Even though it seems that using a mirror was beginning to be commonplace in competitions, it would still be a decade before the rear-view mirror was patented and officially incorporated into automotive production by Elmer Berger.

Levitt would continue to write and participate in the occasional public event, but as of 1912, all traces of her disappeared. Her name vanished from the newspapers until 1922, when she was found dead in her Upper Baker Street apartment in London. The causes: a morphine overdose to alleviate the effects of heart disease and measles.

She left her sister an inheritance of £224 (about £5,000 or $7,000 today), but the money was not what mattered. By then, her name had gone down in the history books, cars were more and more common on the road, and it was no longer strange to see a woman at the wheel.

There are no comments yet