It was the year 381 when Egeria left her home in the Roman province of Gallaecia (in what would now be El Bierzo) to discover the world on foot. She crossed Europe’s borders and continued to Constantinople on Roman roads and many other secondary roads, finally reaching her goal: Jerusalem. Though she did travel by boat for some of the way, the roads were indisputable protagonists on Egeria’s journey.

The 4th century was at its end, and though the Western Roman Empire was beginning to crumble, its impressive network of roads continued to connect practically every place on the map.

Did Egeria follow A Planned Route?

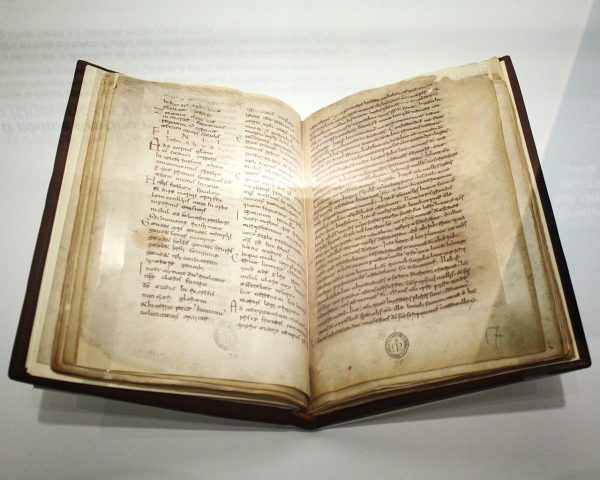

At the end of the 19th century, Italian historian Gian Francesco Gamurrini was shuffling through codices, manuscripts, and documents from a library in Arezzo (Italy), when a codex written in Latin caught his eye. It was in two parts: the first was composed of fragments by Saint Hilary of Poitiers. The second contained what looked like letters written during a trip to the Holy Land in the 4th century.

This second part piqued the historian’s curiosity. Even though several pages were missing, right away, he could see it was a copy (made by a monk in the 11th century) of a first-person narration written by a woman. It told of the places she visited and the people she met on her journey.

Manuscript of Egeria’s travels (11th century), preserved in a library in Arezzo (Italy), the Biblioteca Comunale. Lameiro (Wikimedia Commons)

Manuscript of Egeria’s travels (11th century), preserved in a library in Arezzo (Italy), the Biblioteca Comunale. Lameiro (Wikimedia Commons)

Gamurrini began an investigation to find out who this woman was who had authored these pages and managed to travel so many kilometers (on horseback, on a camel, on a donkey, and exhausting days on foot, as she recounted) from Hispania to Jerusalem in three years. He finally came across Egeria, a woman probably from a wealthy family in Gallaecia. “What is clear is that she was a great lady. Or at least an important woman. That is the only way to explain how she had such freedom with herself and her time, in addition to traveling like she did, without any money problems and with the company of a large entourage,” explains Carlos Pascual in the book, Viaje de Egeria: el primer relato de una viajera hispana (Egeria’s Journey: The First Story of a Female Hispanic Traveler).

It’s also possible that she traveled alone or with just a few people, and that she had support from influential people and perhaps even a letter of safe-passage signed by Emperor Theodosius. What does seem clear is that Egeria’s voyage was not haphazard. Her route had been carefully planned and studied. Surprising though it may be, this was not so unusual at the time.

What kind of travels did they do in the 4th Century?

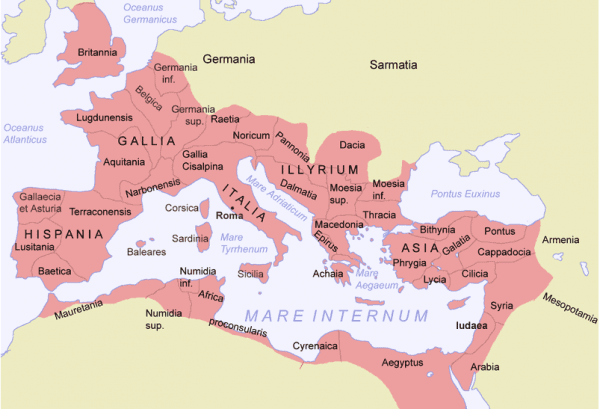

Whether for political or economic reasons or simply for the pleasure of seeing new places and cultures, the voyage was well-known in Greek and Roman cultures. To strengthen their empire, the Romans built a large network of roads that covered much of the territory and reduced travel time considerably. These roads were used by the army, merchants, travelers, and for the cursus publicus (the state mail and transportation service). This network covered about 80,000 kilometers in all.

There would be lodging houses or taverns every 20 or 30 kilometers along these roads for travelers to rest. They were so common that some travelers measured distances by the number of stops along the way.

The Roman Empire at its height (2nd century). Jani Niemenmaa (Wikimedia Commons)

The Roman Empire at its height (2nd century). Jani Niemenmaa (Wikimedia Commons)

With the arrival of Christianity, religious pilgrimages like the one begun by Egeria added to the pull of travel. Our traveler left what is now El Bierzo (in Castilla y León), took the network of roads, and followed the Via Domitia, located in the south of France, until she reached present-day Italy. There, she took a boat to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul, in Turkey).

Once there, she continued to what would become the West Bank, where she visited places like Jericho, Bethlehem, Nazareth, and Jerusalem. In 382, she continued her journey through Egypt, Mount Sinai, Syria, and, once again, Constantinople.

Mount Sinai, northeast Egypt. Vlad Kiselov (Unsplash)

Mount Sinai, northeast Egypt. Vlad Kiselov (Unsplash)

In her letters, which she addressed to her “dominae et sórores” (ladies and sisters), Egeria enthusiastically narrates her impressions of learning about new places and cultures. “As I’m so curious, I want to see it all,” she once wrote.

Was Egeria a pioneer in travel literature?

Egeria’s writings cut off in the spring of 384 in Constantinople. Perhaps her further writings were lost forever, or she may have died before she could start the journey back to Gallaecia. “Meanwhile, my ladies, light of my life, please remember me, whether I am alive or dead,” we read in her last letter.

Egeria was not the first woman to take a trip of this sort, but she was the first to record it in letters. These writings show us her courage and character, but also what it was like to travel on the world’s roads more than 1,600 years ago.

There are no comments yet