For the Romans, the saying ‘curves ahead’ wouldn’t make much sense

18 of April of 2018

What comes to mind when we think of the Roman Empire? Its buildings, its disciplined army, its coins and accounting system? Probably all of these, as they all greatly influenced the development of our own civilization and are today a living memory of Roman culture.

But if there is something really characteristic of the Roman Empire, it is the network of Roman roads, which allowed everything else to develop. Thanks to this prolific system of roadways which crossed all of Europe, it was possible to take construction know-how to other cities conquered by Rome, to transfer large armies wherever they were needed, and to unify Europe under one accounting system.

But it is not only remarkable that the Romans, with their ‘primitive’ (in a purely chronological sense) technology, could build such a wide-ranging network of roads crossing hundreds of valleys. What is also striking is the way in which these roads were constructed. Wherever we look we can see straight lines crossing countries and connecting cities. For the Romans, the saying ‘curves ahead’ would not make much sense.

How were Roman roads built?

In his article Roman roads from a modern perspective, Jesús Rodríguez Morales highlights the fact that, already in the 2nd century BC, roads were built by private companies following a tendering process, and that all roads had kerbs. This is gleaned from a text by Livy (174 BC):

‘These censors were the first to award contracts for paving the streets in cities with stones, the roads with gravel, for using bricks and also for building bridges at numerous points.’

In the same text, Morales talks of three types of Roman roads: dirt tracks, or viae terrenae; roads using gravel, viae glarea iniectae or stratae; and roads paved with stone, or viae lapide stratae. The last two are the ones we know today as Roman roads, and there is general consensus over how most of them were built, though there wasn’t only one way of building them.

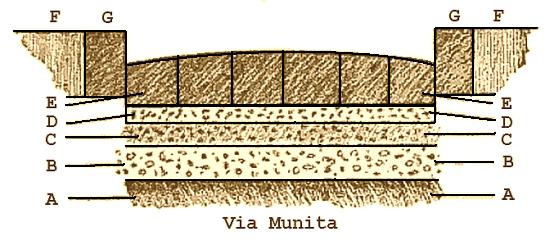

Different layers of the substructure of a Roman road in Pompei. (A) Packed and levelled earth, (B) Statumen (stones) (C) Rubble, broken stones and lime, (D) Nucleus (Kernel or bedding), (E) Dorsum (stone blocks), (F) Crepido (raised sidewalk), (G) Edge stones. Source and more information: J. D. Redding.

In the 17th century, Nicolás Bergier put forward the idea that there were four one to one-and-a-half-metre thick layers surrounded by fulci or side drains. The Romans attempted to maintain the same width of road over the entire Empire, though lack of building materials or construction difficulties meant that some of the roads were rather narrower.

Although most of them were built as roads with a standard width, the sides were dismantled near churches and grazing fields when stone was required elsewhere, and this was the cheaper option. These roads generally fulfil two characteristics:

- They are mainly straight, or at least relatively straight, and it is interesting to note just how straight they are compared to our modern roads, which occasionally follow much more indirect routes to make space for railways, which need to be straighter.

- They have minimal incline, sometimes over hundreds of kilometres. It is rather amazing to verify with a level that the Romans were able to plan roads which crossed the whole of the Roman Empire without any great climbs, spanning huge distances and significant geographic features. Thanks to this, beasts and people didn’t tire as much.

This doesn’t mean the Romans didn’t do curves. The photo at the top of this article shows a slight curve. When the lay of the land made building in a straight line very difficult, the Romans built curves, but they tried to avoid them given their inefficiency. And in order to do so, they used the most advanced technology of the time.

The importance of technology in construction

Today, most building projects are first carried out with virtual tools, as in the case of the Guggenheim museum, for example. That’s why when we look at the past we find it hard to see construction tools as advanced technology. But there were several of such tools which helped make the Roman Empire a great civilisation:

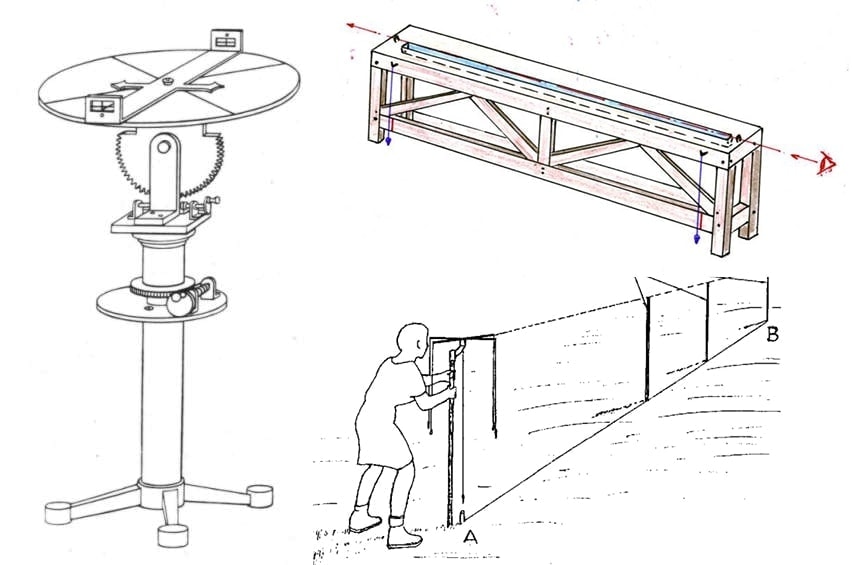

- The dioptra (on the left of the drawing), a device similar to a today’s tachymeter or theodolite, for measuring vertical and horizontal angles and the distance between their vertices using trigonometric relationships.

- A chorobates (top right) was a useful instrument for levelling the ground. In fact, the level in use today is a technological evolution of this.

- The groma (bottom right) was comprised by a vertical pole with various crossbars mounted at ninety-degree angles on a bracket which could turn. It was incredibly useful for checking alignment over many kilometres.

Sources. Dioptra: H. Schöne, Wikipedia. Corobate: Nerijp (CC BY-SA 3.0), Wikipedia. Groma: Cienciahistorica.com

Dioptras were useful over long distances, especially at night when using torch markers. Chorobates were used as ‘local’ levels (for short distances), although the longer it was, the more accurate the results over medium distances.

Likewise with the groma, the longer the wood or pole, the more complicated its use with plumb lines, but the greater the accuracy over longer distances. This levelling system, when coordinated with vertical markers on the ground (metae), turned these tools into very advanced technology, capable of projecting roads.

Particularly long Roman straight roads

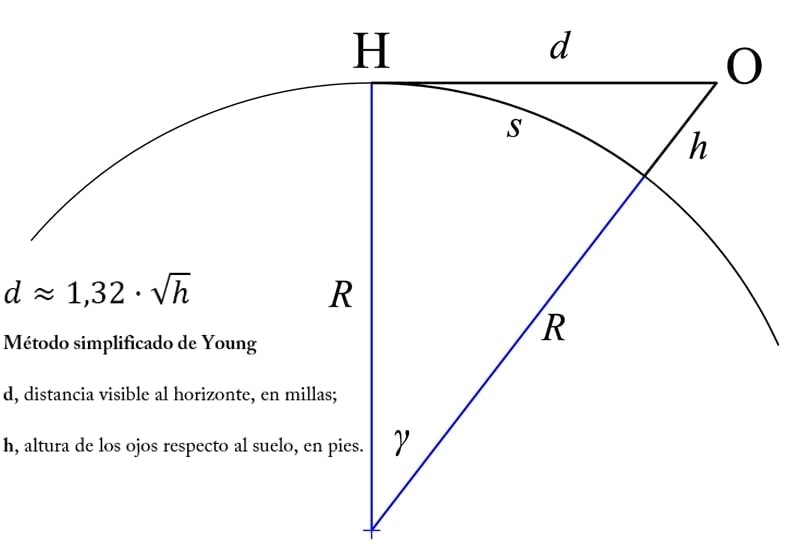

Due to the fact that the Earth is round, somebody sitting on the seashore looking out to sea will see no further than 5km before the curvature of the water hides the rest of the surface from view, according to the Young method. Different human heights and more detailed calculations provide similar results.

Source Jeff Conrad (CC BY 3.0), Wikipedia.

Método simplificado de Young |

Young’s simplified method |

→ d, distancia visible al horizonte, en millas |

→ d, visible distance to the horizon, in miles |

→ h, altura de los ojos respecto al suelo, en pies |

→ h, height of eyes above the ground, in feet |

Although the Romans relied on scales, towers and hills to help then draw their lines, some particularly long roads seem rather remarkable. One of these is the Via Appia, covering more than 90km and running from Rome to Terracina. Which, at ground level, implies projecting a construction nearly 20 times the visible horizon.

Using Young’s simplified equation, to have a view over this entire Roman road we would have to stand at a height of 550 metres. Bearing in mind that Rome is about 37 metres above sea level and Terracina 22 metres above sea level, and that there are no hills worthy of note between the two, this road seems even more remarkable.

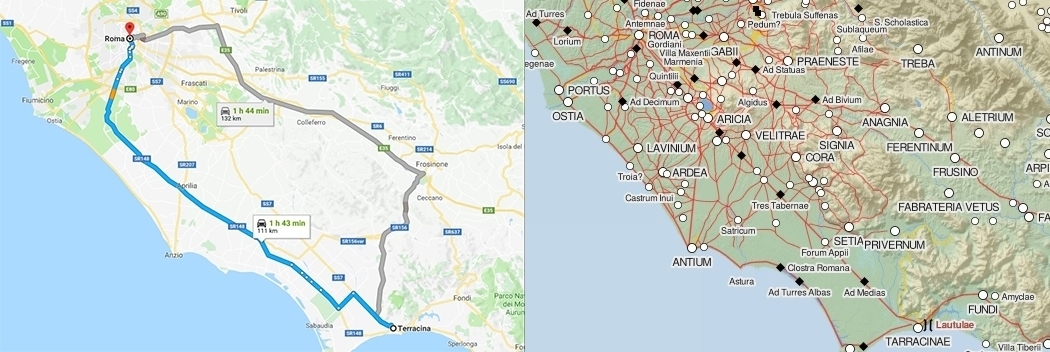

Source: Left Google Maps. Right. Dare.ht.lu.se

These two maps, Google road maps on the left and Lund University Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire on the right, show the cities of Rome and Terracina (Tarracinae). On Google maps we can see how the SS7 road diverts between Cisterna de Latina and Albano Laziale to follow the Via Appia, although back then a series of bridges crossed this marshy area.

The same holds true for other exceptionally long roads, such as the Via Aurelia (55km), the straightness of which could only be analysed using modern techniques and aerial photography (Sterpos, 1970).

The advantages of building in a straight line

Rosa Méndez Fonte, Doctor in Humanities and specialist in Galician Heritage and Society, wrote in Las vías romanas en Galicia (Roman roads in Galicia) that, together with a preference for high ground, ‘another characteristic of these roads is the preference for straight lines’, which provides both military and trade benefits. Designing elevated paths and roads and avoiding curves had certain advantages:

Higher up means less vulnerable

In Roman times, life wasn’t as calm and peaceful as it is today (with a few exceptions) in the West. Back then, there were very few kingdoms, states, countries or fiefdoms which weren’t at war with the Romans.

Defending the borders was therefore essential, and in order to do this constructions tended to be built upwards. This habit was copied by subsequent civilisations, as it also provided advantages in the event of flooding or other climatic events such as heavy snowfall.

A straight line is the shortest distance between two points

Source Pxhere.com

Considering that the Earth is round, as we have seen above, Roman roads are in fact arches on the ground, albeit spanning the shortest route between two points (or, say, between Rome and Terracina).

Given this advantage of the straight line, Roman armies were able to mobilise very quickly, and with a flexibility that other nations lacked. As a result, the Romans had an important military advantage over the others.

Swifter trade meant more money for investments

The network of Roman roads we now see spread over the map wasn’t built in a day. It required centuries of preparation, design and construction, though credit must be given to the speed of Roman construction. Today, building a road is a fairly easy task, but back then it was a complicated engineering undertaking.

A large part of the money required to build these roads (if we remember, most of them were privately constructed) came from the taxes that merchants and citizens had to pay. With optimal roads making for significantly shorter journeys for merchants, the Roman Empire paid for itself very quickly (at least for its time).

The Romans built in straight lines not only because it was easier than doing bends, but because this made roads more efficient to use. The Romans didn’t invent roads, as records show that roads were already being built thousands of years before, but they did develop a system which allowed them to be built quickly, efficiently, at an affordable cost and in a way that made them long-lasting.

There are no comments yet