Exploring the connections between abstract art and construction

Nuclear fusion in general, and the ITER project in particular, could be the most innovative undertaking with the aim of securing the availability of energy for future generations. This project is one of the most prodigious enterprises in the industry which those of us working on the site are unlikely to encounter again. More than 6,700,000 man-hours went into building this unique masterpiece. Many may not appreciate that ITER is imbued with an essence that goes beyond that of construction sites, because ITER is grounded in layers of art. We had the pleasure to reveal them in an enthusiastic artistic dialogue with the renowned artist José Manuel Ballester when he visited the site in August 2019.

What differentiates art and the construction of ITER is purpose, but we should not underestimate the commonalities between the two. During Mr Ballester’s visit, we worked together to link some elements and perspectives of the site to the essence of some of the most prominent artistic movements of the 20th century, associating the work performed by almost 3,000 men and women with that the artwork of prominent modern artists who shaped the avant-garde art of our era. All those elements are encompassed within a single construction project which, like art, is universal, appealing to the sensitivities of all nationalities and transcending borders in the spirit of the intercultural nature of ITER.

The volumes of ITER will soon be filled or covered with equipment and installations that will one day fulfil our desire for clean, unlimited energy, after which this living museum will be hidden forever. The artistic journey with Mr Ballester was probably the most exciting visit to the site I have ever made and it was also, at the same time, my most fascinating “museum” tour.

On the left: reinforcement grid in one of the Tokamak walls.

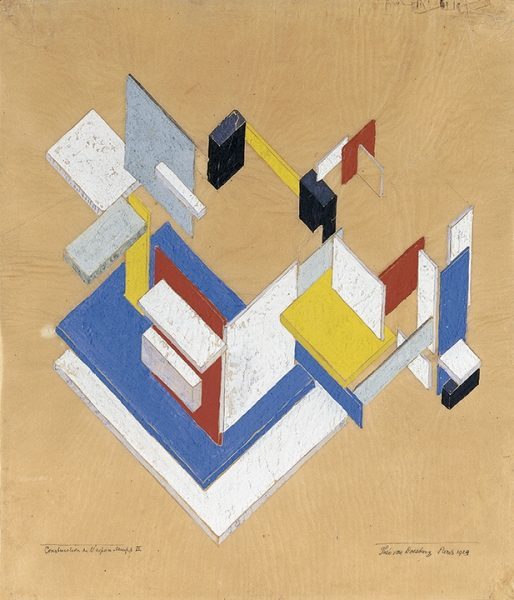

On the right: Theo van Doesburg’s Composition in Gray (Rag-Time), 1919.

Every story has a beginning

Step one of the Vinci-Ferrovial-Razel (VFR) venture in 2013 was to build a mock-up reproducing a sector of the bioshield walls (one of the most complex areas of the project). It was our Rosetta Stone, where the different languages on the site merged, finding the right combination of space and shape: reinforcements overlapped with concrete, with gaps left for cavities, couplers and plates. This concept of radical birth is reminiscent of artists like Kazimir Severinovich Malevich, who reshaped the meaning of art in the first half of the 20th Century. The radical abstract forms of Malevich’s Suprematism bring us closer to the genesis of art, losing all composition, colour, form and shape. For example: The lines and squared shapes of the openings and embedded plates of the ITER’s Tokamak are a permanent tribute to the revolutionary forefathers of Suprematism. See the image of the openings in the Crane Hall side by side with Malevich’s Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying, 1915.

On the left: detail of the openings in the Crane Hall.

On the right: Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying, 1915.

Surrealism and modern art were also flourishing in the first decades of the last century. A prominent example can be found in the populist art of Fernand Léger. His work evolved from Cubism towards a form of art that aimed to speak to the people linked to the industrial revolution. He was enthused by the technological and industrial revolution of his time, just as we are fascinated by the revolution in energy and technology today. His art prompts us to reflect on the importance of humanity in the construction industry. The parallels are striking when we look at this photograph of work on the Tokamak alongside Fernand Léger’s Les constructeurs (detail), 1950.

Manual work in the Tokamak Complex.

From genesis to patterns

Traces of Suprematism can be found in other examples of cubism and constructivism, which were emerging across the rest of Europe after World War I. Colour is largely absent from the Tokamak Complex for now, but the strict patterns of the reinforcements, punctuated by the round earthing devices and circular plates in various shades of grey, produce a temporary composition that could have inspired Van Doesburg, Braque, Tatlin, Gris or the Cubist Picasso. For example, Doesburg’s Construction in Space-Time II from 1924 pictured below. Van Doesburg was obsessed with geometrical abstraction like his master Vasili Kandinsky and he devised the term Concrete Art.

Theo van Doesburg, Construction in Space-Time II, 1924.

Cubism became more elaborate in the Op Art movement. Abstract paintings aimed to blur the spectator’s vision, allowing them to feel movement and imagine forms that were not really there, usually in black and white. In the work of artists like Victor Vasarely, the composition undulates as if the surface were deforming before the viewer. The effects and principles of Op Art were reproduced on the ITER site when the reinforcements for the Neutral Beam Cell were installed. In the cylinder of the central pit, the square openings of the Port Cell were suddenly interrupted by the round shapes of the Neutral Beam inlets. Misaligned surfaces created a discontinuity in the vertical walls of the pit. It was one of the most complex areas we built. The process of creating the 3D design reinforcement layouts led to plenty of blurry eyes in our Engineering teams, as if they were visiting the Vasarely Foundation in Aix-en-Provence. This comparison is best shown in the image of the Reinforcement in Neutral Beam Cell openings (photographed below) and Vasarely’s Vega, from Album I in 1955.

Reinforcement in Neutral Beam Cell openings.

From flatness to volume and back again

In 1960s Brazil, the seeds planted by Van Doesburg and his Concrete Art movement evolved into a new kind of art: the Neo-Concrete movement led by Grupo Frente. Their work rejected the materialistic approach adopted by their predecessors and seeking to portray the human experience through a less restrictive form of art. The result is an art that is more personal, more oriented to the human experience. Like our construction teams, art is made up of individuals with feelings, senses and beating hearts.

In nuclear construction, we tend to think that projects are created solely through procedures and clearly-defined rules. Everything is square, everything is programmed: reality appears to be robotised. But managing high-performance teams like the ones at ITER is more complex. Project direction in the VFR consortium’s Project Management Team was largely characterised by this procedural approach, but this was topped up with an essential dose of personal touch. Collectively over the years, we experienced feelings such as motivation when faced with ambitious technical challenges and a sense of success when our efforts paid off, but there was also frustration and defeat. During this time, our lives were marked by other milestones, such as birth, friendship, illness, fear in response to global pandemics, and even death, and this strengthened our bonds as human beings. In many cases, these ties will last long into the future because the VFR team is very human. It is a conglomerate of multinational professionals with an extraordinary heart, a humanity that exceeds their technical capabilities, a team of people that will be difficult to repeat I always say that the VFR team is the best team I have ever been part of. This is why the concrete poured by VFR at ITER has many aspects of the Neo-Concrete. We can perceive the essence of work by artists such as Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Clark in the concrete details present all over the site.

From complex to simple

This complexity and determination to transcend two-dimensional space gradually made way for simplicity and minimalism emerged after World War II. A good example of minimalism, and one of the movement’s pioneers, is Donald Judd. His art seeks to expunge the hierarchy of objects and to present a clear space, a highly purified form of beauty. The platform created by the movement led to the development of new types of art in the shape of objects, furniture and architecture.

Judd himself designed chairs, beds, shelves, desks and tables based on the same principles as his paintings and sculptures. Simplicity of form is the core of good engineering and the basis for any good design. Our engineers were tasked with nothing more nor less than keeping each aspect of the project as simple as possible. One excellent example of the necessity of simplicity is by seeing a photograph of the openings in the bioshield wall beside Judd’s Untitled, 1988.

Openings in the bioshield wall/central pit.

With more to come…

In part two we continue our exploration of art through the ages as inadvertently expressed through the behemoth undertaking of building ITER.

There are no comments yet