The development of artificial intelligence is a challenge that has occupied the industry and the scientific community for many years since John McCarthy coined the term in 1956 during a summer course at Dartmouth University, USA. During these 65 years, progress has been coming in waves, alternating moments of unbridled optimism with others of helpless disappointment.

In the last decade we have witnessed a flourishing of solutions based on artificial intelligence that has led many to speak of a new golden age for this discipline. This growth is due to the joint action of 3 factors:

- The availability of new algorithms and tools that make it easier to develop new applications.

- The abundance of data from the internet and social networks that facilitate training processes.

- Greater processing capacity thanks to the development of specific processors such as GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) or TPUs (Tensor Processing Units).

Today, the presence of artificial intelligence is already ubiquitous. We use it to receive purchase recommendations from our favorite mobile apps, to magically get our photos labelled or to get suspicious emails automatically discarded as “spam”.

Through these services, artificial intelligence has the power to change our lives, but as is often the case, with great power comes great responsibility.

Can technology be immoral?

As we delegate part of our daily tasks to algorithms, can we guarantee that the principles and values of our society are maintained?

François Chollet, in his wonderful book “Deep Learning with Python”, Second Edition, published by Manning Publications puts it like this:

“Technology is never neutral. If your work has any impact on the world, this impact has a moral direction: technical choices are also ethical choices.”

This point is especially relevant if we consider, as Mr. Chollet points out that, “in a largely tech-illiterate society like ours, the response of an algorithm strangely appears to carry more weight and objectivity” (than that of a human being) [..] “despite the former being a learned approximation of the latter”.

One of the first attempts to establish the rules of behavior of artificial intelligence was given by Isaac Asimov in his well-known 3 laws of robotics:

- First Law: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- Second Law: A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- Third Law: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

However, despite their undoubted literary value, these rules have no practical use in today’s real world.

Like human, like algorithm

With the current degree of development, artificial intelligence systems are capable of making decisions autonomously, but they would always base their decisions in prior information provided by humans. Thus, a Computer Vision algorithm designed to classify photographs between those containing dogs and those containing cats will be able to build its own rationale to decide which answer to give in each case. However, this will always depend on what has been learned from a previous exposure to thousands of training images labeled as “dog” or “cat” by humans. In other words, it is us humans who, with the information provided to the algorithms, influence the way in which they will behave later.

Maybe it is not such a big deal to mix cats and dogs, but let’s imagine an algorithm used to help a HR department screen the CVs they receive. What if the algorithm left out valuable candidates? Or even worse, what if the algorithm discriminated candidates based on age, sex or race using prejudices acquired during its training?

To avoid these situations, it seems clear that regulatory frameworks will need to be established to ensure that ethical values and principles such as human rights, diversity or inclusion are built-in in artificial intelligence systems. This way we will prevent human prejudices from creeping into algorithms, which will later adopt and expand them.

In this regard, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has drafted a recommendation on the ethics of artificial intelligence. It is an important advance, although it is only a recommendation and the ultimate responsibility for its implementation will lie within the member states.

The trolley problem and autonomous vehicles

The problem with ethics is that it is not always easy to determine what is the acceptable solution to a problem. The Trolley problem is one of the most well-known experiments to help us understand it is not always easy to tell right from wrong. It goes like this:

A runaway trolley is heading at full speed towards a group of 5 people tied to the tracks and who will die inevitably. Luckily, there is a lever than can divert the trolley to another track where there is another person tied to the track who would also die if hit by the trolley. If you had the option to pull the level to divert the trolley, would you do it?

If you still have any doubts about the problem, you can watch this video from the Netflix’s sitcom “The Good Place” where it is explained in a fun (and a little bloody) way.

The difficulty of this experiment is that there is no correct answer. On the one hand, we could think that it is better that only one person dies instead of five. On the other hand, by pulling the lever you will play an active role in the death of that one person. Additionally, would your decision change if the one person was a child and the other 5 were elderly people? What if you personally knew any of them?

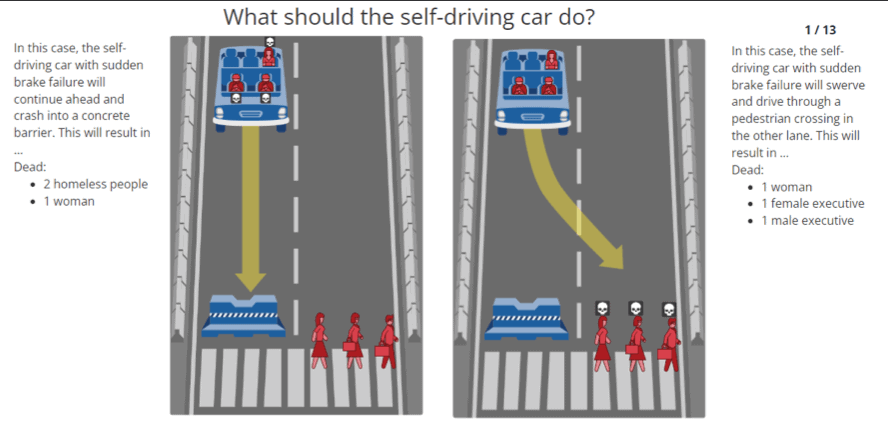

Although this theoretical dilemma was designed more than 40 years ago, it has recently come back to the fore as some researchers believe that future autonomous vehicles will face very similar situations. For example, in case of an unavoidable accident, what criteria should drive a vehicle´s behavior? Save its occupants at all cost? Minimize the number of possible victims, even if that means sacrificing its occupants? Reduce the cost of compensations due to manufacturer liabilities?

In an attempt to find answers to these questions, the M.I.T. launched an experiment known as the Moral Machine in which people were asked their opinion on which was the best decision an autonomous vehicle could make in several scenarios derived from the trolley problem. These answers could then be presented to algorithms as the generally accepted behavior so they can learn from them.

However, this approach to the problem is not shared by the entire community. Some scientists believe that these scenarios are highly unlikely to occur on real roads and that, if they did occur, they cannot be reliably acted upon by any real-world control system in the way that the M.I.T. experiment suggests.

Takeaways

As artificial intelligence gains a foothold in our lives, it is necessary to establish a framework of rules that allows us to ensure that the world continues to function in accordance with the principles accepted by the majority. These rules will help us prevent erroneous data or individual prejudices from being magnified by algorithms in the form of unjust or immoral services. Governments and private companies must work together to establish, use, and ensure compliance. By doing it this way, artificial intelligence, besides making our lives better, will also help us to be more human.

There are no comments yet